Special Issues

“Kathryn Bigelow: A Visionary Director” Special Issue 19.3 (Fall 2021)

Guest editor Frances Pheasant-Kelly

Excerpt (Intro): Until April 2021, when Chloé Zhao became only the second woman to achieve Best Director in the estimation of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the mantle had been held for eleven years by Kathryn Bigelow. Winning the Oscar at the 82nd Academy Awards in 2010 was a pivotal moment in cinema history for which Bigelow is widely acknowledged. What also caught the headlines in 2010 was the fact that she achieved the award for The Hurt Locker (Bigelow 2008), a film that had only modest box office success at the time of its release in comparison to its main rival, Avatar (Cameron 2009).

Articles

Brooklyn: gendered Irish migration to the United States

By Carolina Rocha

Excerpt: By choosing to build a family and home in America, Eilis embraces domesticity and belonging to a new national community, following the steps of previous generations of Irish immigrants who moved to the suburbs, had access to education and white-collar jobs, and thus separated themselves from Irish concerns and politics (Flynn 2011, 19). Brooklyn, however, tests the Irish female immigrant’s resolve to embrace her new identity as an Irish woman in America.

The filmmaker’s presence in French contemporary autofiction: from filmeur/filmeuse to acteur/actrice

By Lourdes Monterrubio Ibañez

Excerpt: Facing Maïwenn’s image on the screen, the actresses – now spectators of the documentary on which the film is based – angrily criticize what they consider to be Maïwenn’s narcissistic film, and not a documentary about them. Once again, the filmmaker ironically references the stereotypical narcissism associated with both actresses and autofiction, turning it into self-criticism on both counts. This irony thus completes the circular structure and the protagonists of the autofiction become spectators of it in order to, once again, construct a parody that offers criticism of the cinematic industry and vindication of the actresses, denouncing the professional discrimination they endure.

Powerful women, postfeminism, and fantasies of patriarchal recuperation in Magnificent Century

By Deniz Zorlu

Excerpt: “Magnificent Century looks admiringly at women’s acumen and resilience in successfully carving out and attaining positions of power and influence in a world of harsh patriarchal domination. However, it also turns physical violence against these strong, aspirational women into a visual attraction in scenes that serve to re-assert patriarchal domination. That some of the most widely watched YouTube clips from Magnificent Century are those misogynistic scenes of gendered power reversals, which impose patriarchal dominance to deprive high-status women of their power, are the direct result of a masculinist culture latent in Turkey. Yet that Magnificent Century has been so internationally successful indicates that both postfeminism and popular misogyny appeal to viewers far beyond Turkish borders.”

The cultural politics of Jennifer Lawrence as star, actor, celebrity

By Gregory Frame

Excerpt: “While there is no evidence to suggest this was staged, her stumble up the stairs at the 2013 Academy Awards to accept her trophy played a crucial role in creating this impression: she is not ‘trained’ to be a Hollywood star; there is a real person that exists beneath this rather tenuous façade. Indeed, as she rather bluntly stated when asked what had happened in the post-ceremony press conference, ‘What do you mean? I fell down. Look at my dress!’, pointing exasperatedly at the beautiful, elaborate garment she wore to collect the award. 4 This forthrightness is revealed no more clearly than in her interviews: as she told talk show host Jimmy Fallon in May 2016, she had to be sent swiftly for media training after she joked in an interview that Kim Basinger, her co-star in The Burning Plain (Guillermo Arriaga, 2008) had died. 5 She claims to become utterly dumbfounded when in the presence of actors she perceives to be more famous and important than her, saying when she met Tilda Swinton that she kept prefacing everything she said to her with ‘I love your work’. It is this unvarnished, guileless quality that has functioned to establish her image as one of ordinariness; that, as has been claimed by many, ‘Lawrence is constitutionally unable to not say what she thinks.’”

“Romantic Female Friendships as Resistance: Subversive Web Series in the United States and India”

By Molly Bandonis & Namrata Rele Sathe

Excerpt: “Episode 4 of Ladies Room opens on a scene with about fifteen women inside the dressing room of a comedy club. Having a last-minute attack of stage fright, the star performer, Naima, has locked herself inside the restroom. The other women try and lighten her mood by asking her to run her gags by them. The women are loud and raucous; they heckle and swear unselfconsciously, recounting outrageous anecdotes about men who insist on sending them ‘dick pics’ without their consent. One of them whips out her mobile phone to show the others a series of such pictures, which she describes as a ‘deck of cards,’ as she flicks through them. The women grouped around her react with a resounding ‘ewww,’ signaling their distaste for such unsolicited pictures. This inspires Naima to come up with her punchline: ‘Guys think they’ll impress us with their dick pics. They should send pictures of their bank balance instead and then we’ll talk.’ This scene encapsulates some of the major thematic preoccupations that underpin the series including unconventional performance of femininity, reconfigured gender and sexual dynamics within romantic encounters, and the impact of neoliberal economic forces on interpersonal relationships in India.”

“Archival Research as a Feminist Practice”

By Catherine Martin

Excerpt: “Women are still too often banished to positions of secondary importance and their roles in shaping our mediated world diminished or ignored. There is much to be done before we can argue that we have truly achieved the feminist promise of broadcast history in general, and archival research in particular: to provide a deeper understanding of the way gender roles and expectations have shaped our past and present. In the case of media history, this means tracing how attitudes toward women, and women themselves, have shaped the representations through which we evaluate our lives. To put it another way, we cannot have an open and honest debate about women’s current and future social roles without a deeper understanding of the ways in which media representations of women’s actual lived experiences have been shaped, and how they have shaped our society. And one key to achieving this understanding is archival research.”

“From couch scenes to kare kare: visual pleasure, restoration drama and feminist film”

By Bridget Orr

Excerpt: “The film is not shot from the habitual over-the-shoulder position but moves, very slowly, to track characters from varying vantage points. Ada, whose point of view frames the first shots, actively resists the male gaze and later shares it with Baines. Baines himself becomes the most spectacular object of visual attention when his naked body is shown in large close-ups, observed by Ada. The film divides the patriarchal subject in two, with both Baines and Stewart becoming in some way subject to Ada. And in an amazing scene of castration, Ada loses a fingertip and takes up a full – if still rather open – position of subjectivity usually defined as male. The movie is a textbook example of how female direction might challenge filmic narrative – even if it remained unable to escape from a colonialist representation of Maori that consigned them to the margins.”

“‘Philosophy in the Kitchen’: image, domestic labor, and the gendered embodiment of time”

By Olivia Landry & Christinia Landry

Excerpt: “Here the ontology of time unfolds via a feminist history of housework and its frequent, yet often overlooked, visual representation in European art cinema. If early cinema began with the Lumière Brothers’ image of workers leaving the factory – that is, symbolically with the end of work – then new wave art cinema of the longer postwar period expresses a type of work that has neither beginning nor end – that is, the endlessness of work. Contrary to Farocki’s enduring claim, ‘Most narrative films take place in that part of life where work has been left behind’ (2002), Torlasco’s digital archive of housework proves otherwise. Image after image of women engaged in housework excised from the archive of European cinema lucidly shows the vast presence and visualization of labor in cinema. Torlasco brings into focus the often overlooked images of European cinema that are obscured by dominant historical narratives. Although there appears to be scant narrative relevance attached to housework in cinema, it is nonetheless always present – present yet ostensibly insignificant. That an image may always be present but invisible to the viewer is a phenomenon of our cinematic socialization.”

“Water Color: Radical Color Aesthetics in Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust”

By Diana Pozo

Excerpt: “In examining Daughters of the Dust, I would like to highlight a form of color design that, rather than separating particular colors, or imagining colors as unchanging and/or separate from their objects, portrays colors as liquid, flowing into and around one another. This style is painterly in that figure and ground seem to be part of one continuous surface. I call this type of color design water color, not only because of its association with the fluid painting medium of watercolor, but also because of the way in which water itself has no fixed color, instead picking up colors from the sky, the trees, or other surrounding objects as well as changing its hue according to sky and clouds. Daughters of the Dust, set on a barrier island in South Carolina, portrays water in a multitude of colors, from dusty blue, to green, to gray, to lavender, to indigo. Moreover, the white costumes of the majority of female characters in the film take on different hues: subtle pinks, golds, and lavenders, as the quality of natural light shifts over the course of the day.”

“Tout(e) Varda: the DVD collection as authorworld”

By Karen Boyle

Excerpt: “Certainly, Tout(e) Varda gives a (commercial) visibility to Varda as a filmmaker and invites a reading of her films as a body of work. Given the enduring marginalisation of women within the film industries, the literal visibility of the female writer/director is something feminist critics continue to invest with political significance (Tasker 2010). In this respect, the title of the collection requires comment. By placing the ‘e’ of the feminine form (toute) in brackets, the collection immediately draws attention to Varda’s gender as something which troubles the categorisation and marketing of the authorial collection. She is visible from the outset as a feminine form, in a context in which the masculine is assumed. The use of the bracket keeps both in view, expressing a doubleness 48 K. BOYLE but also, arguably, a hesitation: the identity of the coherent authorial presence is one which Varda holds at something of a distance, but also one invested with political (feminist) significance. The ‘death of the author’ might be an interesting critical project, but it does nothing to destabilise male-dominated versions of film authorship which continue to dominate film discourse, not to mention festivals, awards and histories.”

“‘From grade B thrillers to deluxe chillers’: prestige horror, female audiences, and allegories of spectatorship in The Spiral Staircase (1946)”

By Tim Snelson

Excerpt: “Although the reviews and pressbook articles universally highlight the performances of the female stars and the centrality of their characters, the film is never discussed as a woman’s film. As contemporary critics such as Mary Ann Doane have suggested, the collective term was used for ‘male critic’s derogatory New Review of Film and Television Studies 177 dismissal’ of certain texts, a point seemingly not lost on either studios or critics of the day (Doane 1994, 284). In a 1944 column entitled ‘Shall We Join the Ladies’, renowned New York Times critic Bosley Crowther complained that the term ‘woman’s picture’ had been ‘badly and recklessly used’ as a term of debasement. Citing examples of female-centred texts as diverse as Mrs. Parkington (1944), Laura (1944), and Our Hearts Were Young and Gay (1944), Crowther stated that ‘any picture that handles the subject of women well is universally accepted. And, when it doesn’t, it’s a “woman’s picture”’ (1944, X1). Thus like horror, the term woman’s picture was seemingly avoided as a demarcation for such films. Instead, the press material attracted women by implication and association, rather than signposting their releases as woman’s films and potentially putting off both men and women through perceived negative terminology.”

“Teen heroine TV: narrative complexity and sexual violence in female-fronted teen drama series”

By Susan Berridge

Excerpt: “The recurring feminist critical celebration of female independence is particularly problematic in relation to teen drama series, in which the age-related vulnerability of teenage characters is a prominent generic theme. On the one hand, the female protagonists of these series are certainly depicted as highly independent, physically and/or mentally strong, witty, and perceptive. They drive the narrative forwards and control the gaze. On the other hand, at least in early seasons, they depend upon their parents for food, shelter, and money and their vulnerability is frequently emphasised. Jenny Bavidge (2004) expands on this tension between the independence of the teenage heroine, prized by feminist scholars, and their age-related vulnerability, stressed in the series themselves, arguing that the female adolescent heroine in literature and on television is both a source of optimism and ‘a potential victim, willing or otherwise, of the projections or temptations of the corrupt adult world’ (46).”

“Phantom ladies: the war worker, the slacker and the ‘femme fatale’”

By Mark Jacovich

Excerpt: “It is therefore significant that most of the female characters that have come to be seen as classic examples of the femme fatale are rarely seen in public space, but are almost always located in domestic interiors or nightclubs, where they wile away their time in boredom as they await the return of their men or are presented to the world as spectacles that display their partner’s power. Furthermore, their demeanour and attire also contributes to this image: they are often dressed in evening gowns, bathrobes and lingerie, and are frequently reclined in a bored and languid pose. The world in which they operate is not one of productive labour but of leisure and consumption, even if they are an object of someone else’s leisure and consumption.”

“‘I’m not your mother!’: maternal ambivalence and the female investigator in contemporary crime television”

By Amanda Greer

Excerpt: “Until recently, maternal ambivalence has been considered a taboo subject, thought to negate the idealization of the mother as a selfless figure. Motherhood, historically, has been established as a necessary component of feminine identity. It is assumed that most women will have children someday – those women who choose not to have children are seen as failing to adhere to womanhood’s narrative. These assumptions are rooted in a reductionist view of female biology: women should have children because they can. The sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s finally brought forth, arguably for the first time in dominant popular culture, a discussion of maternal ambivalence – of conflicting positive and negative emotions circling motherhood.”

“Seeing Lucy’s perspective: returning to Cavell, Wittgenstein and The Awful Truth”

By Catherine Constable

Excerpt: The utilisation of class in Lucy’s masquerade serves both to render Jerry an outsider to the Vance household and to provide her with access to particular constructions of available female eroticism. While Lucy’s colouring prevents her from instantiating the dumb blonde performed by Dixie Belle, her reprise of the number begins with an imitation of the previously parodied Southern drawl. Lucy has no access to wind effects – she exhorts her largely stunned and disapproving audience to use their imaginations – however, the design of her costume aids the impression. The dark sequinned lapels of her short, fitted bolero jacket overlap with the sequinned trim beneath the bust-line of her dress, emphasising her cleavage, while attention is drawn to the movement of her lower body by two long layers of fringe falling from her hips and mid thighs. Lucy’s first two renditions of the wind effects are shown in long shots, she provides the sound – an exuberant, rising ‘whoo hoo hoo hoo’ – grabbing handfuls of fringe and flinging them up in the air on the reprise. Her dance repeats aspects of Dixie Belle’s, while also incorporating moves from the shimmy, the black bottom (clapping her hands together and then patting her bottom on either side) and finally burlesque as she clasps her hands behind her head and fails to perform a pelvic tilt, saying ‘I never could do that!’

“Women’s rights in Serbian cinema after 2000”

By Ivana Kronja

Excerpt: Affirmation of the mother’s desire represented in her encounters with her young lover ‘fully clothed’, in conversation, is also one of the film’s advantages, although this part of the story is dramaturgically under-developed, which gives it a certain ‘stagy’ effect. The main characters of Saša and Lana could have also been given more space to provide better explanation of their motivations and Saša’s inner drama, on which we have limited information. We see all external, but almost no internal, reasons for their behavior. Although much of the story’s attention is given to other aspects of the drama (family problems etc.), Take A Deep Breath still is a coming-out film – an important sub-genre of gay cinema which describes a young person’s first experience with homosexual love (Giannetti 1993, 405). In conclusion, although a bit conservative in representing female desire both towards other women and towards male lovers, the film shows that it is not necessary to show ‘everything’ to provide affirmation of a woman’s rights and choices.

“A certain age: Wes Anderson, Anjelica Huston and modern femininity”

By Cynthia Felando

Excerpt: One of the more intriguing aspects of Huston’s work with Anderson is that across the three films her characters become progressively more independent and less accommodating to the assortment of dysfunctional characters around them. The shift is suggested by each film’s introduction to Huston’s character. In The Royal Tenenbaums, Etheline’s on-screen introduction occurs during the very dense exposition montage, in the film’s past, immediately after her husband Royal tells the three kids of his plans to move out because he and Etheline are separating. As the voiceover narration explains Etheline’s devotion to her children, she is first shown during the course of a long-duration shot that pans from the family mansion’s object and memento-filled stairwell to a small closet- or nest-sized space where Etheline is surrounded by her three young kids, Margot, Chas and Richie. She is talking on the phone (in Italian) and making changes to the kids’ busy activity chalkboard chart labeled ‘Schedule of Activities’, which includes character-building karate, Italian and ballet lessons. Moreover, when young Chas requests a check for nearly 200 dollars, she trusts him to prepare it himself. Shortly thereafter, in another montage sequence that re-introduces the key players as they look directly into the camera, presumably a mirror (from their perspective), Etheline is shown in her office, applying a touch of eye makeup and sliding a pencil into her upswept but slightly askew and slightly graying hair. Most noteworthy is that, when she is finished, she smiles a bit – and she is the only one of the ensemble during this montage to do so.

“The feminine appeal of British horror cinema”

By Alison Peirse

Excerpt: These female-centred horror films can be perhaps more profitably understood by turning away from much of the existing work on British horror film, and looking instead to critical work on woman’s film, particularly Mary Ann Doane. In The Desire to Desire: The Woman’s Film of the 1940s, Doane explains that the woman’s film is ‘in many ways a privileged site for the analysis of the given terms of female spectatorship and the inscription of subjectivity precisely because its address to a female viewer is particularly strongly marked’ (1987, 3). Her work on classical Hollywood cinema explores female protagonists with significant access to point of view structures and narratives that ‘treat problems defined as “female” (problems revolving around domestic life, the family, children, self-sacrifice and the relationship between women and production vs. that between women and reproduction)’ (1987, 3). She nuances the relationship between woman’s film and genre, explaining that woman’s film does not possess ‘consistent patterns in thematic content, iconography and narrative structure’ (1987, 34), but it does ‘have a coherence and that coherence is grounded in its address to a female spectator.

“The male gaze is more relevant, and more dangerous, than ever”

By Kelly Oliver

Excerpt: Just as the camera possesses the woman’s body in this way, film creates the desire to possess. Voyeurism and fetishism produce the desire to possess. In more recent work, Mulvey argues that Hollywood has created not only the star system, but also and moreover, the need to supplement the moving image with still images, including posters, photos-stills, and pinups as a means to fix and thereby possess the objects presented in moving images. Insofar as film both creates objects and resists fixing them in time and space, Mulvey identifies a compensatory aspect of the male gaze’s need to master and control its object. The movement and fluidity of filmic images works to both create the illusion of mastery and undermine it. The objects created through film are framed, set-up, and controlled, and simultaneously beyond reach of the desire to capture and possess. Film both captures the image and releases it.

“The Text in the Third Degree: Gay camp recoupment in What Ever Happened To …? and High Heels”

By Bruce Williams

Excerpt: David Greene’s film textualizes the cult phenomenon of Aldrich’s work as well as the ambiance in which such a phenomenon is played out. In the hypertext, the obviously gay character of Baby Jane Hudson’s accompanist, played by Victor Buono, is weak and unassertive, dominated by the Cockney mother with whom he lives. Greene’s personal manager, on the other hand, is a wheeler-dealer, and is in essence, a movie queen gone amuck. Never allowing Jane to actually drive him home following their meetings, he has her drop him off in front of a mural located in the center of Hollywood and depicting Hollywood idols, all integral to gay iconography. The manager is immediately accosted by a group of young guys, most likely street hustlers, who wish to introduce him to a new boy. Suggesting that the manager also dallies in the rent boy trade, this sequence underscores by implication the financial difficulties which have led him to take a menial job in a video rental shop, where he and Jane meet. The gay character is thus transformed from passive and stereotypical to aggressive and manipulative.

“Delinquent daughters: Hollywood’s war effort and the ‘juvenile delinquency picture’ cycle”

By Tim Snelson

Excerpt: The New York reception of the ‘juvenile delinquency pictures’ evaluated the films in relation to the shifting understanding of young women’s behaviour in and around Times Square, and the legal policies adopted to tackle it. But while elements of the classic moral panic around youth (Cohen 2002) are in place here – with everything from jive music, poolrooms, and candy stores selling ‘salacious literature’ blamed for increasing licentiousness in the area (New York Times 1994a, 1944d) – there was little agreement on the causes of such female youth delinquency. Indeed, media representations of the phenomenon were conflictual, and at times directly confrontational. As McRobbie and Thornton argue of moral panics in our ‘multi-mediated’ present, youth ‘folk devils’ are ‘vociferously and articulately supported in the same mass media that castigates them’ (1995, 559). In the case of Times Square’s bobby soxers, this process was played out not just within newspapers with opposing political allegiances, such as the pro-Republican New York Journal-American and liberal PM, but even within different sections of middlebrow papers such as the New York Times. The pages of these popular media invoked the teenage bobby soxer as a symptom of wartime’s moral crisis and as a sign of prospective post-war affluence.

“Jane Campion’s The Piano: melodrama as mode of exchange”

By Agustín Zarzosa

Excerpt: What makes The Piano a melodrama is the stark comparison between two notions of marriage, that is, two systems of exchange. The first notion of marriage involves the exchange of women among men; the second one involves the exchange of vows between a man and a woman. Despite the moral ambiguities about Ada’s (Holly Hunter’s) participation in the exchanges depicted in the film, the film clearly denounces the violence and injustice that arranged marriage involves. As a melodrama, the film condemns arranged marriage and proposes love marriage (and egalitarian relationships between men and women) as a viable alternative.

“‘There is a reason why Sporty Spice is the only one of them without a fella …’: the ‘lesbian potential’ of Bend it Like Beckham”

By Katarina Lindner

Excerpt: The term appropriation is often used to theorise the ‘non-normative’, ‘subversive’ or ‘unintended’ readings of particular films, scenes or images by particular audiences. Whatling, for instance, sees appropriation as a viewing process in which ‘the focus of meaning of a film text is altered’ (1997, 3). As Whatling herself notes, such a conceptualisation raises important and problematic issues surrounding intent and agency. There is, in fact, a more general sense that accounts of lesbian and gay reception often assume ‘a problematic degree of selfconsciousness and intentionality’ on part of the viewer, which poses fundamental questions with regard to lesbian identity and how it might be defined (White 1999, 196). For instance, when referring to a ‘lesbian look’, as Whatling does, does this imply that only self-identified, self-conscious ‘lesbian’ spectators can engage in such a look? Can straight women ‘look lesbian’ (self-consciously and/or intentionally or not)?

“Mulvey as Political Weapon”

By Kelli Fuery

Excerpt: The parrhesia Mulvey practices is political insofar as her theorization of the gaze was a demand for the rethinking of female identification and pleasure within cinematic spectatorship. Her risk, whilst not of life or death, was embedded in the engagement of political debate in the specific cultural and historical landscape of 1970s British tertiary education. Merck notes that when Mulvey wrote Visual Pleasure in 1975, ‘the feminist movement of the early 1970s was mostly composed of educated middle-class women, but relatively few were employed as academics in a male-dominated profession’ (2007, 3). At a time where film studies in Britain grew out of the BFI, Mulvey’s risk lay in the parrhesiastic act of exposing’s women’s relationship to pleasure via the scopophilic gaze, through revealing her own. Foucault claims that the danger involved in being a parrhesiastes is that ‘you risk death to tell the truth instead of reposing in the security of life where the truth goes unspoken’ (2001, 17). For Mulvey, such a death was one of potential exclusion – not just from patriarchal society or even the ivory tower of academia – but more pivotally, exclusion from the truth of one’s own affective, sensory experience regarding objectification.

“The Clash Between Theater and Film: Germaine Dulac, André Bazin and La Souriante Madame Beudet”

By Charles Musser

Excerpt: Dulac often distinguished the cinema of her present from the cinema of the future. She felt that the public was ‘holding back its evolution, considering it simply a distraction and a successor to the theater’. Yet as she saw it, the cinema should be ‘an art which owed nothing to the others and which possessed an extraordinary abundance of new expressive features’.15 The theater offered or expressed purely exterior acts while the cinema possessed the opposite potential and was ideally suited for ‘visualizing the smallest nuances of the soul, of one’s interior life’.16 For Dulac in the mid-1920s at least, this was the essential difference between cinema and theater. The differences between her film version of La Souriante Madame Beudet and the play from which it was adapted exemplify these distinctions. It is tempting to see her adaptation of the play as its negation, in effect quite literally turning it inside out so that the interior lives of the characters, which are hidden in the play or expressed indirectly through dialogue and action, are made manifest on the screen.

“What Can She Know, Where Can She Go? Extraterritoriality and the Symbolic Universe in the Alien Series”

By Sasha Vojkovic

Excerpt: My aim here then is to explore the discursive potential of this ‘constitutive outside’. I am implying also that Lorraine Code’s question ‘what can she know?’ will be related to alternative discursive and narrative spaces where women can act as knowing subjects (Code 1991). To explore the New Hollywood cinema’s potential to thematize the ‘outside’, we need to go far away into the future, into the darkest corners of the universe for it is there that the father-apparatus, or the central computer called ‘the Father’, will finally crash. On the basis of the films from the Alien series, Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), Aliens (James Cameron, 1986), Alien 3 (David Fincher, 1992) and Alien Resurrection (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 1997) I will suggest that woman as subject par excellence, and as constitutive outside of a specific ideology, can in itself, to put it in Butler’s terms, become open for contestation. I will argue that this is dependent on an alternative symbolic network based on alternative fabulas and world-views.

Lorna’s Silence and Levinas’s ethical alternative: form and viewer in the Dardenne Brothers

By Joseph Mai

Excerpt: Ethics is not cold moral deliberation by an autonomous individual, but is the restless perception that one’s ‘own’ self living for another growing within it, taking it over. If film is to have some bearing on ethics and moral deliberation, we will first have to redefine along these lines what it means to be a self in the world. A film should not reinforce our political or intellectual habits; it should persecute us and goad us into a confrontation with the other who constitutes us.

“Zero Dark Thirty – ‘war autism’ or a Lacanian ethical act?”

By Agnieszka Piotrowska

Excerpt: My point in this paper has been that Maya’s commitment to her cause is not engendered by her alleged lack of empathy but rather her conscious and stubborn commitment, however problematic and controversial it might be, to her chosen path. That commitment could be theorised as her ‘not giving up on her desire’ in Lacanian terms, thus constituting an ethical act. Maya’s desire is fuelled by conscious and unconscious mechanisms, which the film hints at but does not spell out. What a Lacanian psychoanalytical reading can bring into a discussion of this film and others is a reminder of the unknowingness that is also a part of the human condition. There is a lack of reasonableness about Maya which disturbs and interrupts the viewers’ accepted norms, particularly male viewers, and from that standpoint alone one could argue that it comes down in a line descending from Antigone, another inflexible stubborn and beautiful woman rejecting the rules and procedures of the patriarchal systems of her time in ways which some might view as immoral.

“My Mulvey”

By Sarah Cooper

Excerpt: I first read ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ in the mid-1990s, when writing on feminist and queer theory prior to working on film. Its influence was formative to my thinking, and although my own theoretical frameworks were more diverse, insofar as they stretched beyond psychoanalysis and encompassed sexualities beyond the heterosexual, there was something about the urgency of the argument in this text that spoke to me across these potential dividing lines. As a woman and a feminist, as well as a film viewer who had watched classical Hollywood movies unquestioningly in my teenage years, I found the argument on the destruction of pleasure in the name of progressive politics provocatively appealing. As I assessed the extent to which cross-identification with the male gaze structured the way women were required to see if they were to gain pleasure from these films, I perceived for the first time my transvestite clad viewing position, to coin the terminology of her ‘Afterthoughts’ on this essay, and this made me restless.

“BETWEEN BRECHT AND ARTAUD Choreographing affect in Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun”

By Elena del Río

Excerpt: In Fassbinder’s films, the historical framework that constrains the body is indivisible from the affective, preverbal, signs through which the body voices the said historical constraints. In aligning the body with affect, Fassbinder is less divesting it of its semiotic and social status than complicating this status with an added dimension—indeed tracing the social to its corporeal site of inscription. As Fassbinder’s films show, it is not in spite of social and ideological determination, but precisely by virtue of the latter’s relentless pressure on the body, and in response to it, that the affective body emerges. If ideology constructs a repressed body, the affect repressed is bound to return in one form or another. The body thus becomes the site where a transfer takes place between the abstract social or ideological meanings and the material individual ways of responding to and embodying those repressive meanings.

“‘Thrills and chills’: horror, the woman’s film, and the origins of film noir”

By Mark Jancovich

Excerpt: This association between the thriller and horror becomes even more pronounced in the reviews of Murder, My Sweet, RKO’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s Farewell My Lovely. For example, the New York Times claimed that the film continued a tradition of murder and violence that had begun at the start of the year with Experiment Perilous, a classic example of the Gothic (or paranoid) woman’s film that the paper had clearly identified as a horror film on its release. This link between the thriller and the Gothic (or paranoid) woman’s film was also cemented by the claim that Experiment Perilous had operated ‘to delight the armchair gumshoes’ (T.M.P. 1945b). Furthermore, while the Gothic (or paranoid) woman’s film was described as an investigative narrative that appealed to the same audiences as Murder, My Sweet, the Chandler adaptation itself was also associated with horror through the claim that its release consolidated a reputation established by the success of Experiment Perilous and Woman in the Window before it: ‘such hits in a row is enough to turn any respectable theatre into a chamber of horrors, so that there is no telling what sort of black magic the Palace might come up with next’. Thus, Murder, My Sweet was described in terms that emphasize an association with horror, with the New York Times referring to the film as ‘pulse-quickening entertainment’ and the New York Daily News describing it as ‘another spine-tingling melodrama’ (Cameron 1944b).

Reviews

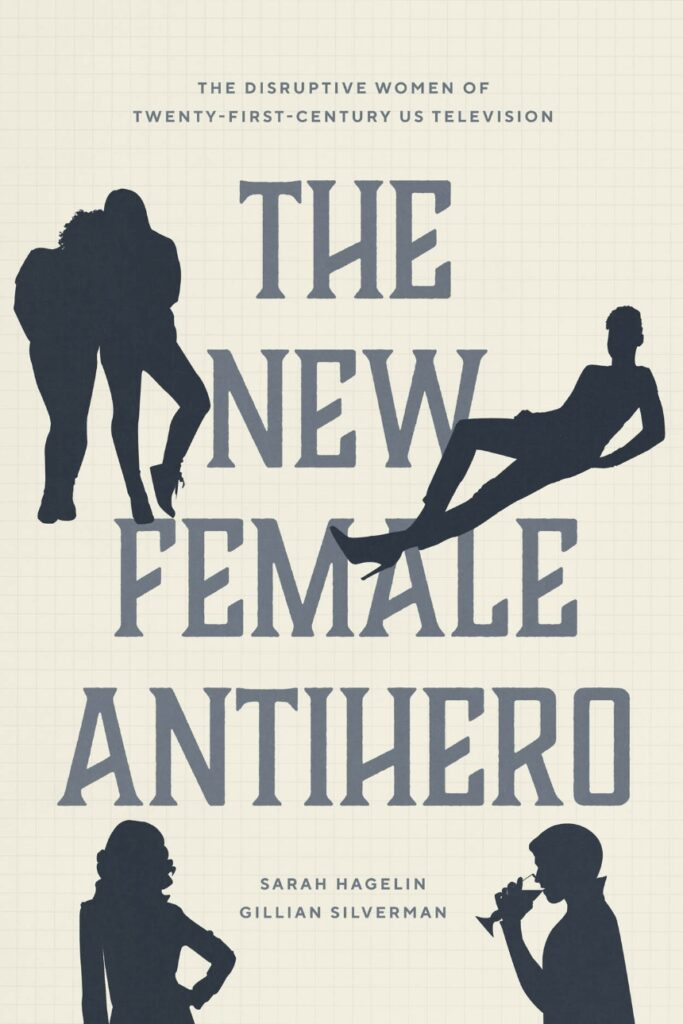

The new female antihero: the disruptive women of twenty-first-century US television by Sarah Hagelin and Gillian Silverman

By Arya Rani

Excerpt: Hagelin and Silverman have produced a jargon-free and engaging study to appreciate and admire the flawed women on TV. Instead of an investigation of the quality of feminist politics in female antiheroes, the authors reckon with the feminisms reflected through these characters in American television. Moreover, the book is extremely resourceful in understanding the genealogy of feminist research in drama and comedy. Although the project is rooted in American socio-cultural boundaries, the theoretical model of the ‘new female antihero’ has a wide scope to be explored in the context of OTTs that target a global audience.

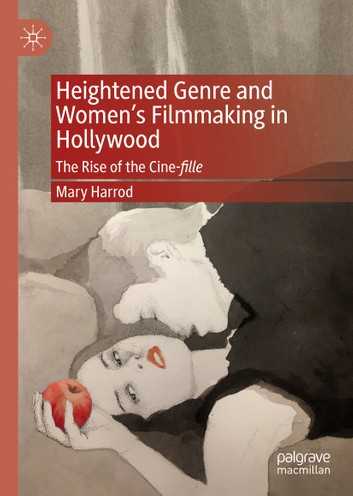

Heightened genre and women’s filmmaking in Hollywood: the rise of the cine-fille by Mary Harrod

By Sonia Lupher

Excerpt: Through the neologism ‘cine-fille’, Harrod brings the importance of women’s viewing practices into play when considering their creative output in a mainstream industrial context, [arguing that] women-directed Hollywood films conflate embodied, affective, and intellectual addresses that speak to the genre literate contemporary viewer.

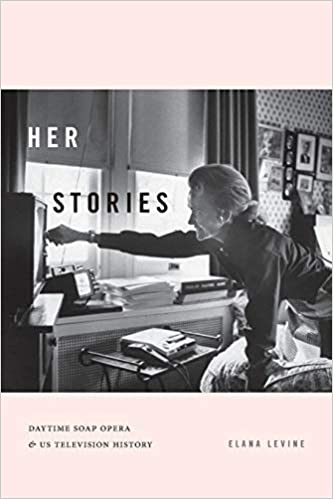

Her Stories: Daytime Soap Opera & US Television History by Elana Levine

By Lauren Wilks

Excerpt: “With Her Stories, Levine contributes a valuable refocalization of the history of American television. By using soaps as a through line, Levine provides profound insights into the shifting standards, approaches, and trends that shaped representation and industrial structure over the course of seven decades. Her Stories makes visible how American television envisioned and interacted with its audiences, both real and imagined, through a comprehensive analysis of one of television’s most long-standing and impactful genres.”

Lesbian Cinema after Queer Theory by Clara Bradbury-Rance

By Katrin Horn

Excerpt: Considering its geographic and temporal scope as well as its bold theoretical claims, Lesbian Cinema after Queer Theory is a relatively short book. Each of the six chapters makes its point in approximately 20 pages, with preface, intro, and conclusion limited to even fewer pagers. Arguments are often accordingly presented in dense prose and in a concise manner, which assumes the reader’s familiarity not only with the specific films but also the book’s larger cinematic and theoretical references. Frequent summaries of prior points and references to other chapters, however, are successfully employed to help orient the reader and underline the cohesiveness of the argument. Moreover, the book is rich in detail, especially when it comes to framing its readings of films within histories of various film genres and types, ranging from US film noir, sports movies, and mid-century melodrama to French art cinema and pornography.

Agnès Varda Between Film, Photography, and Art by Rebecca DeRoo

By Richard Neupert

Excerpt: Rather than offering a comprehensive overview of Varda’s output or a narrow thematic approach, DeRoo refocuses attention on several key works and specific strategies in Varda’s career. DeRoo wants to be sure that Varda is neither reduced to a few canonical films nor removed from the cultural politics and contexts that shaped her work. All Varda’s films and installations exist in dialogue with cultural forces and are as reflexive as they are intermedial. Varda’s ability to override gender and genre barriers while mixing documentary, photographic and narrative strategies is central to DeRoo’s summary of this filmmaker’s unique approach to media production. In work as diverse as le Bonheur (1965), L’Une chante, l’autre pas (1977) or her 2006 Cartier Foundation installation, L’Île et elle, Varda forces her audiences to reflect upon institutions, politics, aesthetics and even our assumptions about spectatorship. DeRoo selects several central works—one per chapter—to highlight particularly pertinent films and installations that clarify how Varda engages with the limits and potential of representation in a highly personal manner.

Blog Posts

A Conversation between Janice Loreck and Aimee Traficante on ‘Provocation in Women’s Filmmaking’

Excerpt: What Loreck is able to accomplish here then, through her insightful analysis of a melange of provocative works by female directors, is to provide an academic perspective on a painfully overlooked sector of women’s filmmaking. In spotlighting these particular texts, Loreck simultaneously confronts the reader with their own preconceived notions of what transgressive cinema can look like.

Cityscapes, Trance States and Wayfaring Women

By Kornelia Boczkowska

Excerpt: In the cinema of walking women, exemplified by films and videos like At Land (Maya Deren, 1944), Two Women, Cléo de 5 à 7, Messidor (Alain Tanner, 1979), Saving the Proof, Vagabond, Wadjda (Haifaa al-Mansour, 2012) and 10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman (Rob Bliss Creative, 2014), wayfaring female characters are the main force driving the narrative capable of transforming everyday spaces and social structures.

Ken Stewart’s review of Hannah Strong’s Sofia Coppola: Forever Young (Abrams Books, 2022)

Excerpt: Strong takes a uniquely modern, journalistic approach to the synthesis of Coppola’s public life and art through analog and digital resources.

Matthew Sorrento’s review of John Stangeland’s Aline MacMahon: Hollywood, the Blacklist, and the Birth of Method Acting (The University Press of Kentucky, 2022)

Excerpt: Like so many female stars of classical Hollywood, her talents far outshined the opportunities given to her. Stangeland’s account of the woman in full should encourage more studies and new fans of the one-of-a-kind star.

“Fatal Attraction” Reboot Reviewed: Giving a Woman a Backstory as a Mentally Ill Murderer Does Not a Feminist Tale Make

By Suzanne Leonard

Excerpt: The 2023 Fatal Attraction asks a question that it answers with a sexist platitude—one of the few it shares with the 1987 version. Whose narrative matters? Not Alex’s, with her daddy issues, unconfirmed pregnancy, and unfocused plans for flight before Dan can collect on his promise to ruin her career. Nor is it Ellen, a daughter with a Jung fixation, who seems perhaps too forgiving of a father who cut off all ties but seeks to punish anyone tangentially in the orbit of a dangerous liaison.

“The Bind of Exceptional Women: Alicia Kozma in Conversation on the Cinema of Stephanie Rothman”

By Maya Montañez Smukler

Excerpt: The exceptional woman essentially functions as a pass for Hollywood as an industry, and sometimes for critics and filmmakers, to mistake the appearance of a handful of women as meritocracy; essentially mistaking tokenism as meritocracy. It’s equally applicable to the gendered labor of directing and film production as a whole, because we could use the same paradigm and apply it to editors and composers, cinematographers, etc.