By Suzanne Leonard

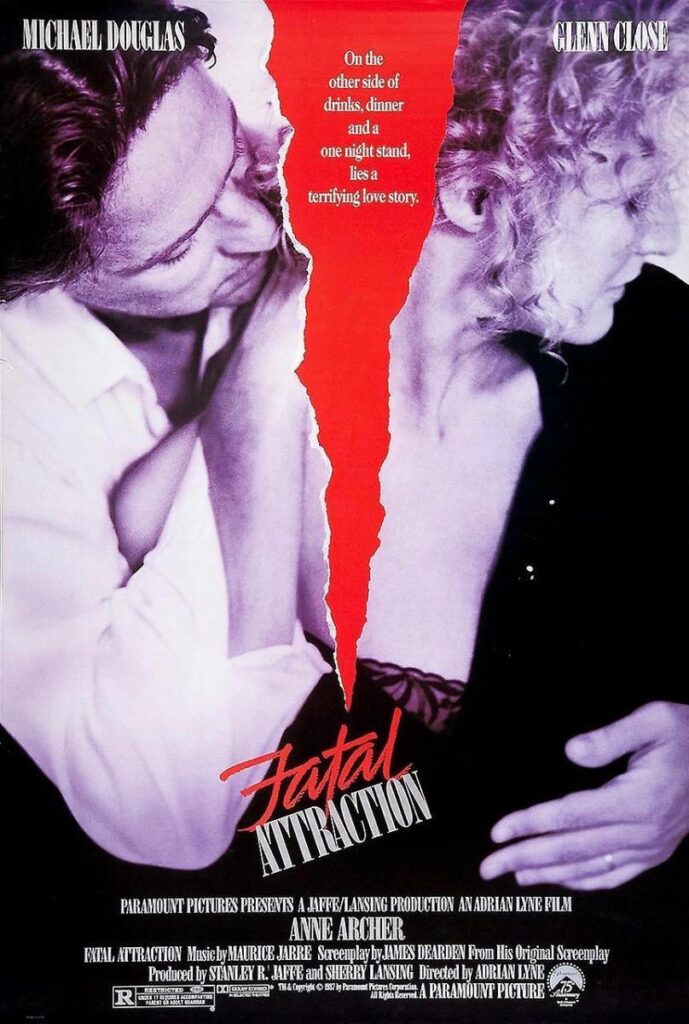

Paramount Plus’s eight-episode reboot of the 1987 film blockbuster Fatal Attraction promised, albeit gently, to offer more insight into Alex Forrest, the never-to-be-ignored femme fatale originally played by Glenn Close. In both iterations, a single-minded scorned lover terrorizes her married paramour, Dan Gallagher, as well as his wife and daughter, after a brief affair. In Close’s capable hands, Alex was sexy and self-assured, and undeniably threatening. The role inaugurated no less than a cultural zeitgeist, wherein the phantasmagoria of a desperate working woman who fears she may never marry or have a child elevated these anxieties into an enduring cultural panic. The reboot has none of these problems nor does it, alas, have any of the original’s potential.

Simply put, the reboot doesn’t stick. It lacks the unforgettable, indelible titillations or atrocities of Adrian Lyne’s genre-defining erotic thriller. Devoid of unbridled sex on elevators, boiled bunnies, or water-logged Psycho-adjacent scenes of vengeful bathroom murders, the reboot formulates itself into a milquetoast murder mystery. Along the way, viewers encounter a familiar familial psychodrama, occasional Rashomon-like plays with perspective, and a jumbled narrative temporality wherein hairstyles are the most salient indications of whether one is viewing the past or present. Finally, there’s a macabre cancer tale, featuring possibly the most upbeat dying person ever, and some pathetically on the nose forays into armchair psychoanalysis—assuming one would characterize Carl Jung that way—featuring Dan’s now twenty-something daughter Ellen.

As a feminist media scholar who wrote a book on the original film, I expected to be most interested in Lizzy Caplan’s portrayal of Alex. In the years since the release of the iconic thriller, it has become more widely known that Close was vocally upset about the film’s treatment of Alex and particularly the reshot ending. In the film’s first iteration, Alex frames Dan for her murder, after committing suicide to the strains of Madame Butterfly. This version concluded with Dan being hauled off to prison, imploring his wife Beth to search the attic, where he hopes she will find tapes in which Alex verbalizes her obsession. In the reshot ending, a capitulation to focus groups who felt that Alex deserved a more punishing finale, Alex breaks into Dan’s home. After a drawn-out physical battle, Alex is gunned down by Beth. Close felt that this conclusion was inauthentic, and vehemently maintained, “I fought it for two weeks. It was going to make a character I loved into a murdering psychopath.”

Oddly enough, the reboot takes exactly what Close railed against and turns it into reality. While one could argue that Caplan’s Alex does gain a backstory the original lacks, there are only a few significant aspects of this history. Namely, she has stalked at least one other married man, her father was a lying narcissist who manipulated and verbally abused her, and her relationships with friends and lovers alike are marred by her erratic emotionality. For all the sympathy these characterizations might invite, Caplan’s persona is nevertheless arguably more diabolical than Close’s Alex ever was. Most horrifically, Caplan’s Alex acts as a bystander-come-instigator in the death of Beth’s mother, a weak swimmer who slips poolside, gasping for air while Alex extends the retractable cover and condemns her to a watery grave.

One of my pet peeves about the media coverage of the 1987 film has always been that Alex is held up as an example of borderline personality disorder. I am not a psychologist, but any decent film scholar knows that it is specious to treat fictional characters like real people—I tell my students this all the time. Yet, I would take this common error over what the reboot achieves, which is essentially to equate mental illness with sociopathy. Caplan’s Alex is mentally ill and seemingly incapable of remorse, as if to suggest the two are one in the same.

More interesting, though I am eager and at once loathe to say it, are the reboot’s flirtations with admitting the realities of white male privilege. The reboot’s opening is as compelling as it is deceptive. Here, a disheveled Dan Gallagher appears at a parole hearing as he admits his guilt for Alex’s murder. This wasn’t a crime of passion, he says, but rather a calculated attempt to stifle the chaos that his affair unleashed on his life. “My position, my accomplishments, everything that I had, and everything that I wanted; next to that, she meant nothing. That she tried to jeopardize it in my mind, meant that I was justified in whatever I chose to do. And I chose rage.” To my profound disappointment, this is all a lie, designed to sway the parole board into an early release. As he tells Ellen in literally the next scene, now that he has been released, his goal is to clear his name. He never killed Alex. Sigh.

For all my critiques of the original film, and believe me, there were many, one of its few strengths was to admit the unknowability of desire, and of the human psyche writ large. Michael Douglas as Dan has no “reason” to cheat; it was a matter of a moment. It was a wife and daughter absent for a weekend, and a willing partner who queries with intention if he knows how to be “discrete.” The reboot refuses this opacity. Instead, Joshua Jackson’s Dan is a hot-shot federal prosecutor who has just been turned down for a judgeship that seemed all but assured; he lives in the Shakespearean shadow of a powerful but unloving and dead father; and his first encounter with his wife on screen suggests the quotidian strains known to any married couple. They are moving houses, and they argued about a movie—sometimes it is just that banal. If only the reboot had allowed itself to simply sit with that. Sometimes risk is just fun—full stop.

Equally flat is the reboot’s attempt to probe the subjectivity of Beth, played by the statuesque Amanda Peet. Her shock at her husband’s betrayal warrants no more than a handful of tearful confrontations. Before you know it, her mother is dead, and so is Alex. Rather than exile Dan from their family home, as in the original, this Beth dutifully drives her husband home from the courthouse after his arrest. Even more far-fetched is Beth’s acquiescence to allow her then eight- year-old daughter to testify at her father’s trial. In the briefest of moments, the show teases audiences with the suggestion that Beth is the one who murdered Alex, and then let her husband pay for the crime. How I longed for that nod to the original. Instead, the reality of Alex’s murder is narratively soporific. The murderer—Beth’s best friend and business partner—is a marginalized figure who acts out of some unarticulated fury, perhaps driven by the cosmic unfairness of having a dying wife, coupled with a quixotic and overcoming urge to help the woman with whom he shares a business. None of the characters has an interior life that feels worth plumbing, although the series ends with the suggestion that we should probably have been paying more attention to Ellen.

The 2023 Fatal Attraction asks a question that it answers with a sexist platitude—one of the few it shares with the 1987 version. Whose narrative matters? Not Alex’s, with her daddy issues, unconfirmed pregnancy, and unfocused plans for flight before Dan can collect on his promise to ruin her career. Nor is it Ellen, a daughter with a Jung fixation, who seems perhaps too forgiving of a father who cut off all ties but seeks to punish anyone tangentially in the orbit of a dangerous liaison. Is it a wife who seems removed? The best friend of the unfairly prosecuted man? The murderer of Alex who promptly marries Beth, and fills in as Ellen’s dad, after Dan’s incarceration? Ultimately, of course, in this hierarchy of mattering it’s the same old, same old: we must care, as always, about Dan. He makes one mistake and suffers for it beyond what is fair or just. The flawed, tragic hero, whose worth is ensured, as always, by the privilege of his race and gender. The mediocre white man—somehow the victor, even in defeat.

Sign up for NRFTS alerts so you’ll know when future articles become available, and check out our latest issue of the journal.