By James Fenwick

Why has Stanley Kubrick, by and large, escaped the #MeToo era unscathed? While other directors have been toppled (with varying degrees of success) from their canonical ivory towers—Alfred Hitchcock, Roman Polanski, Woody Allen—Kubrick remains standing, his reputation and legacy arguably greater than it ever was, particularly with the blockbuster success of the official travelling Stanley Kubrick exhibition. Yet Kubrick’s films, in particular the likes of Lolita (1962), A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999), construct and represent women and women’s bodies in a highly problematic way, while evidence exists of Kubrick’s own exploitative behaviour, alongside that of other powerful men he worked with in Hollywood. Considering all this, is it now time to take full account of the quite often misogynistic representations in Kubrick’s films and how they stem from the production cultures in which they were produced? As Karen Ritzenhoff, one of the few academic voices in calling out Kubrick and his films as misogynistic, argued in 2021, ‘After two years of turmoil in and around Hollywood surrounding the relaunch of the #MeToo movement, the question is whether the “genius provocations” that Kubrick evoked in his films have to be looked at differently under the veil of gender equality, sexual harassment and abuse, and different reiterations of the women’s movement?’ (177-178). My response is yes and I want to set out here why that is the case.

Kubrick’s films have largely escaped the #MeToo movement and the wider ‘cancel culture’ due to continuing auteur apologism from fans, critics, academics, and even his own family.

The #MeToo movement originally emerged in 2006, but it became prominent in 2017/18 following the revelations of the horrific violent sexual crimes committed by Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein over decades. What the #MeToo movement highlighted was how many people who knew of the acts of people like Weinstein had remained silent, but the moment had come to stand up, call out such behaviour, abuse, mistreatment, and violence committed by other men in the film industry, and say ‘no more’. All of the men who were exposed as having committed sexual abuse, harassment, and assault were part of a system in, and beyond, Hollywood that allowed them and their behaviour to be excused in a culture of silence and in a system of power and privilege. What followed was the outing of actors, directors, and producers all guilty of sexual harassment, misogyny, and abuse, both historic and ongoing, against women in the entertainment industry.

#MeToo has led to amplified calls to give a voice to the marginalised, overlooked, and forgotten individuals — whether creative, administrative, or technical labourers — who have substantially less power or agency than the male producers, managers, directors, and executives within the entertainment industry. By empowering these individuals and groups, it is possible to work towards a revisionist film and television history, one in which the understanding of power dynamics, organisation, and even creativity is reframed (Dall’asta and Gaines 2015). Film history has been written and understood from the perspective of powerful men, which has often led to the exoneration of their behaviour and abuses (often to the refrain of ‘it was different back then’), or to excusing it by framing these powerful men as geniuses, artists, and auteurs — what Stefania Marghitu calls ‘auteur apologism’:

“Separating the art from artist is a standard practice embedded in the cultural fields—from painting to literature to film and television—and it is often required when overlooking the amoral or criminal acts of the “genius-artist.” Those that claim historical preconditions make these icons merely products of their time often excuse these behaviors, from Paul Gaugin’s rape of the subjects he portrayed (Adrian Searle 2010) to Alfred Hitchcock’s abuse of actress Tippi Hedren (Brent Lang 2016).” (2018: 491-492)

Take the latter example of Hitchcock. In October 2016, Tippi Hedren alleged that Hitchcock had sexually assaulted her (Gompertz 2016). The director’s behaviour toward Hedren on The Birds and Marnie had involved him obsessively watching her, making advances, and finally calling her into his office, where he made aggressive moves to touch her: “It was sexual, it was perverse, and it was ugly, and I couldn’t have been more shocked and more repulsed” (Gompertz 2016). At the start of this blog post I somewhat overstated the extent to which Hitchcock’s legacy had been ‘toppled’. Despite the revelations, Hitchcock and his work did not vanish. His films still screen around the world and on television and there are books still being published that tout his genius and reinforce his legacy (Miller 2016; Pippin 2017; Isaacs 2020). Arguably, there have been attempts at auteur apologism: that Hitchcock was simply expressing his frustrated sexual fantasies through his art (Thorpe 2016). In response to those who have questioned her allegations, Hedren has stated, ‘They weren’t there. How about that? I was the one living that life. They weren’t. How can they possibly have anything to say about it?’ (Hedren quoted in Lang 2016). However, what should not be possible now is any discussion of The Birds and Marnie without reference to and contextualisation by way of Hedren’s revelations and documented accounts of Hitchcock’s wider problematic behaviour towards women. Hitchcock in the #MeToo era does not mean the erasure of his work (the ‘cancelling’ of his films), but rather it is about foregrounding the material, cultural, and social realities of how he behaved on set and the lived experiences of the women (and others) who worked with him.

Within academia, there have long been ongoing wider projects to study, question, and reframe understanding of the media industries by examining the exploitative practices and cultures that underpin filmmaking both historical and contemporary, identifying and restoring the role of women in film history and film cultures, and finding new approaches and sources towards these aims. A large portion of this work has been conducted by studying a vast array of new archival and empirical sources in which women, women’s labour, and women’s experience of production cultures are foregrounded. See, for example, Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinemas Past and Present (Gledhill and Knight 2015), Contesting Archives: Finding Women in the Sources (Chaudhuri, Katz, and Perry 2010), and the work of the Women’s Film & Television History Network-UK/Ireland (WFTHN). However, within some segments of film and media studies, such as Hitchcock Studies or Kubrick Studies, this work has had little impact (or, rather, little recognition) to date. Kubrick Studies, for example, often acts in self-isolation (though, with signs this is changing) without recourse to considering the methodological and historical questions being posed by other scholarly communities and disciplines, despite the urgency and highly important nature of what is being researched by networks such as WFTHN.

The official Stanley Kubrick travelling exhibition also contributes to the auteur-apologism and the silencing of women.

So what of Stanley Kubrick? I do not necessarily think Kubrick and his films should be ‘cancelled’, not in the sense of trying to remove him or them from film history. That just will not, and should not, happen. Kubrick and his films are too iconic, too popular, too commercially profitable to the likes of Warner Bros. However, I do think it is time to fully acknowledge the misogynistic representation of women in Kubrick’s films, the evidence of his own problematic behaviour toward women in a professional setting, the evidence of his exploitative relationship with media labourers generally, and the allegations against those powerful men with whom he worked. All of this contextual information should be part of discussions of Kubrick and those films with which he is associated going forward, rather than continuing the reductive auteur reflections on his “genius” or his influence. And it should be placed within wider histories of the systemic structural problems in Hollywood, both historically and contemporaneously.

The most obvious and visible incident of Kubrick’s on set treatment of women involves actor Shelley Duvall on the set of The Shining (1980). It emerged as part of a behind the scenes documentary, Making The Shining (1980), in which Kubrick is seen to shout, disparage, and potentially bully Duvall. Interestingly, it was Kubrick himself who allowed this footage to emerge. Why is not clear. But whatever the reason, it does still hint at a powerful male producer’s interactions with a woman on set that is troubling, particularly in light of Duvall’s own mental health issues that existed prior to her work on The Shining. Yet, Kubrick’s behaviour is overlooked (Siddiquee 2017). There are other issues and incidents beyond this particular case, however.

First, the portrayal of rape and the misogynistic violence in A Clockwork Orange (1971), a film that continues to be hailed as a masterpiece (such as during the 2019 BFI re-release), but with no prevailing contextualising information as to its problems. My own research has uncovered the highly inappropriate means by which Kubrick reduced women to sexual objects in the casting of the film and his overriding fixation on casting women based on their body shape, specifically their breasts. This was even the case with those women being cast in roles where it was not obvious as to why Kubrick had to fixate on their bodies. There are similar casting notes for those women considered for the role of sex workers in Full Metal Jacket (1987).

Second, the representation of women and women’s bodies in Eyes Wide Shut (1999), a film that once again reduces women to sexual objects and reveals Kubrick’s preponderance for the ‘Kubrick body type’ (Kolker and Abrams 2019: 70-71; Ritzenhoff 2021). Just as in A Clockwork Orange, women are reduced to sexual commodities for the pleasure and gaze of men.

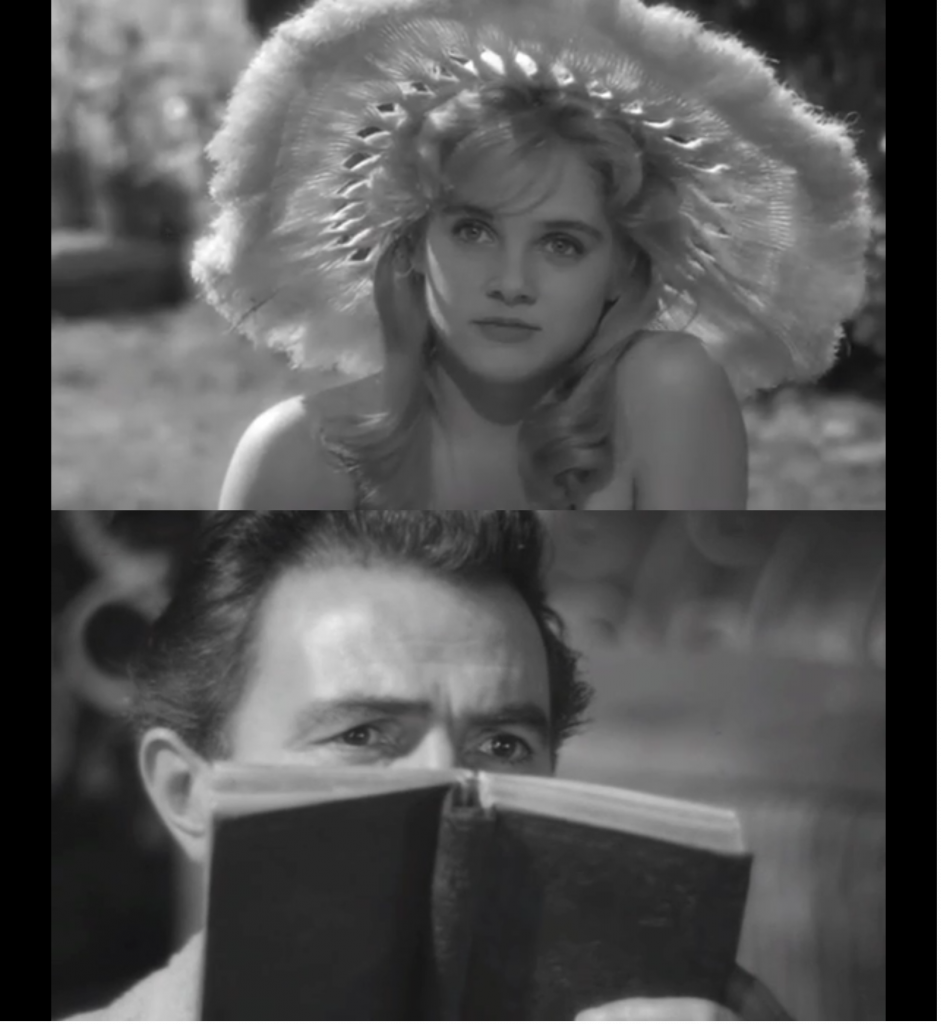

Third, and most problematic of all, is the humorous, casual, and inappropriate representation of paedophilia in Lolita (1962). Indeed, if there is one Kubrick film that should be ‘cancelled’ it is Lolita. It is a film that becomes ever more disturbing as the years pass by, not least because of recent allegations that the film’s producer, James B. Harris, slept with the actor Sue Lyon when she was only thirteen or fourteen (Weinman 2020; Loftus 2020). There were suggestions in the press at the time of the film’s release of some kind of relationship between Harris and Lyon. As such, one cannot escape the realisation that the film potentially allegorises its own production in the light of these allegations. Kubrick and Harris were also controlling the contract and ultimately the life and career of Lyon. Archival evidence shows the pair reducing Lyon to a commercial object to be traded around Hollywood for their own profit. The impact on Lyon was profound. But, once again, her voice, like many other women, was silenced, despite the fact that she specifically pinpointed Lolita as being the cause of her drug addiction, mental health issues, and multiple marriages (Macdonald 1996). Lolita the film represents the material, cultural, and social realities of its production and the control and mistreatment of a young girl.

Much of the above is not new, but these issues, revelations, and allegations rarely make an impact on the perception of Kubrick and his films. I would suggest this is for two key reasons. First, Kubrick was a powerful Hollywood producer and like other powerful, male Hollywood producers, was able to frame his own mythic image and aura that silenced those that worked for him. Kubrick was complicit in his own branding and self-promotion, even feeding stories to major newspapers since the beginning of his career. It served his own means to fashion an image of himself as the tyrannical artist. However, it is a mythical image that obscures the material, cultural, and social realities of production. Second, Kubrick’s films have largely escaped the #MeToo movement and the wider ‘cancel culture’ due to continuing auteur apologism from fans, critics, academics, and even his own family. Those works that do question and provide evidence of problematic and exploitative production cultures are often used by fans to justify Kubrick’s genius (see, for example, this recent review). Meanwhile, the Kubrick family have been instrumental in framing Kubrick’s image and legacy since his death in 1999, even making it their mission to combat any negative discussions of Kubrick and his films.

The official Stanley Kubrick travelling exhibition also contributes to the auteur-apologism and the silencing of women. It is an exhibition that venerates, even deifies Kubrick as a visionary genius, displaying objects selected from the Stanley Kubrick Archive. In that exhibition, you will not see Kubrick’s casting notes for A Clockwork Orange or his letters to James B. Harris about Sue Lyon. But imagine what would happen to our understanding of Kubrick, and those that worked on his films, if they were put on display. The BBC’s Will Gompertz, in his review of the official travelling Kubrick exhibition at London’s Design Museum, noted that, ‘You won’t find out what Kubrick was like, but you will discover what it takes to make a great work of art’ (2019). And this is precisely because the objects on display, curated from a selection of objects predetermined by the Kubrick estate, have been specifically chosen in a bid to further the narrative of Kubrick as artist and genius. But there are artefacts within the Stanley Kubrick Archive that present a very different narrative of the privilege and power of men in Hollywood.

The potential impact of #MeToo on film and media history is in how it can fully contextualise, acknowledge, and take account of the exploitative conditions of production and misogynistic representations of women in films and the voices that have been silenced. Given the wider social, political, and cultural contexts in which we now live, it is surely time to have a frank discussion about the problematic nature of films like A Clockwork Orange and Lolita, of producers like Kubrick and his own behaviour, and of the behaviour of some with whom he worked. I, for one, am doing so when it comes to my own research approaches.

While Kubrick may well have been a family man, as his family is always determined to stress (and as is their right), the issue here is not his homelife, but his professional working environment and the production culture that he managed. It is about his managerial attitudes and responsibilities to those who were employed by him across the full suite of production companies and production roles. It is about the continuing privileging of the artistic myth of Kubrick over that of the industrial reality of modern Hollywood, and of the structures of inequality and power that have for far too long allowed powerful men like him to subvert and undermine precarious, low-paid, or powerless media labour.

Read James Fenwick’s article “Problems with Kubrick: Reframing Stanley Kubrick Through Archival Research” in New Review of Film and Television Studies.

References

Monica Dall’asta and Jane M. Gaines, ‘Constellations: Past Meets Present in Feminist Film History,’ in Christine Gledhill and Julia Knight (eds) Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinemas, Past and Future (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 13-25.

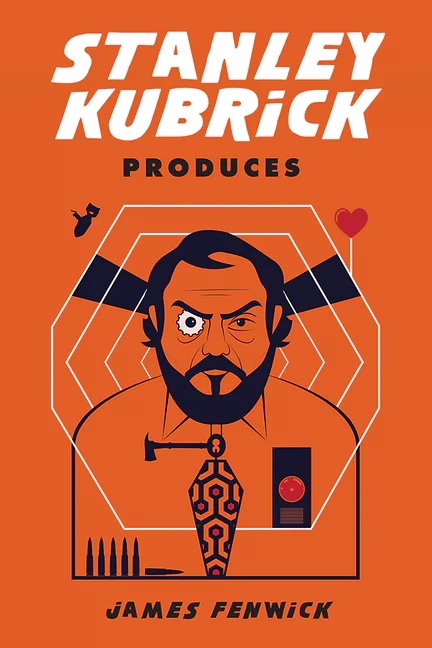

James Fenwick, Stanley Kubrick Produces (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020).

Christine Gledhill and Julia Knight (eds) Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinemas, Past and Future (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015).

Will Gompertz, “Will Gompertz Reviews Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition, at London’s Design Museum,” https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-48040275.

Bruce Issacs, The Art of Pure Cinema: Hitchcock and His Imitators (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Robert Kolker and Nathan Abrams, Eyes Wide Shut: Stanley Kubrick and the Making of His Final Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Jamie Loftus, Lolita Podcast, iHeartRadio, 2020-21, https://www.iheart.com/podcast/1119-lolita-73899842/.

Marianne Macdonald, “Correctness fears keep Lolita under wraps,” August 8, 1996, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/correctness-fears-keep-lolita-under-wraps-1308824.html.

Stefania Marghitu, ‘“It’s just art”: auteur apologism in the post-Weinstein era.’ Feminist Media Studies, vol. 18, no. 3 (2018): 491-494.

D. A. Miller, Hidden Hitchcock (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Robert B. Pippin, The Philosophical Hitchcock: Vertigo and the Anxieties of Unknowingness (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Karen Ritzenhoff, ‘Kubrick and Feminism.’ In N. Abrams and I. Q. Hunter (eds) The Bloomsbury Companion to Stanley Kubrick (New York: Bloomsbury, 2021): pp. 169-178.

Mike Segretto, ‘Review: Stanley Kubrick Produces,’ Psychobabble, http://psychobabble200.blogspot.com/2020/12/review-stanley-kubrick-produces.html.

Sarah Weinman, ‘The Dark Side of Lolita,’ Airmail, https://airmail.news/issues/2020-10-24/the-dark-side-of-lolita.