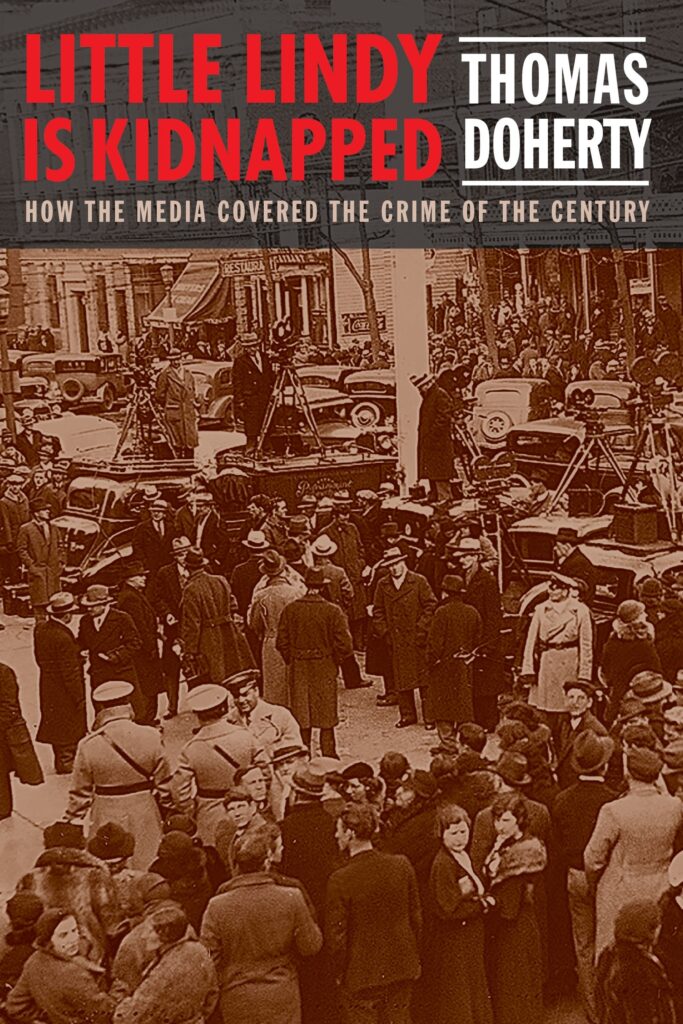

“A spellbinding rollercoaster of a read” – Dr. Kathryn Fuller-Seeley

(Columbia University Press, 2020)

By Thomas Doherty

Epilogue

The Legacies of the Crime of the Century

“No criminal case in the twentieth century cast so long a shadow over American law, politics, and media as the kidnap-murder of the Lindbergh baby. All three realms were fundamentally altered by the case: new legislation was passed, new federal control was asserted over crime, and new protocols were established for electronic journalism. For the justice system, the federal government, and the media landscape, it really was the Crime of the Century.

The Lindbergh Laws

The kidnapping and murder of Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. persuaded most Americans that the laws of the land did not fit the crime and the lawmen were not up to the task. At both the federal and state level, politicians rushed to pass legislation to remedy the oversights. Never again would a kidnap-murderer be beyond the reach of capital punishment; never again would a heinous crime with national implications be left wholly in the hands of local constables and beat cops. Henceforth, a kidnapper risked the electric chair, and the full force of federal authority stood ready to strap him in.

An outraged Congress quickly passed the so-called Lindbergh law, which made kidnapping across state lines or to or from a foreign country a federal crime, with a penalty up to life imprisonment. Passed without a single dissenting vote, the legislation sailed through the House of Representatives. On June 22, 1932, the bill (“a direct result of the Lindbergh baby tragedy”) was signed by President Herbert Hoover. On May 18, 1934, FDR signed legislation amending and strengthening the Lindbergh law to treat kidnapping ipso facto as an interstate crime under the jurisdiction of the federal government and to provide for the death penalty if the victim was not returned unharmed.

State legislatures also acted with dispatch. In California, the Lindbergh name, which had christened so many streets and babies in 1927, inspired a vengeful piece of legislature called “the Little Lindbergh Law.” As home to legions of wealthy Hollywood celebrities, Los Angeles felt especially vulnerable to the threat of copycat baby snatchers. Fan magazines had long featured motion picture stars cradling infants and frolicking with kids around swimming pools in palatial homes, pictures that oozed wealth, privilege, and, to the criminal mind, opportunity. Security was tightened, bodyguards hired. No star wanted a real-life reenactment of the cautionary plotline of Miss Fane’s Baby Is Stolen (1934).

The Little Lindbergh Law made kidnapping for ransom within the state a capital crime—even if the victim was only harmed, not killed. “The day of mush-and-milk handling of such criminals in California is past,” editorialized the Los Angeles Times in 1934 when the first capital sentence under the law was handed down to two malefactors who had kidnapped and tortured but not killed a local attorney. “Their fate could well serve to send a shiver of fear down the spines of gangsters contemplating similar crimes.”

The new laws demanded a new kind of lawman. The feckless New Jersey state troopers and two back-to-back headline-hungry governors displayed “some of the most noteworthy police bungling and political publicity hunting and plain everyday stupidity ever exhibited in connection with a murder case

in this or any other country,” editorialized the New York Daily News. In a scathing series of syndicated articles, Arthur B. Reeve, a popular writer of detective fiction, shared his professional opinion about the real-life detectives in New Jersey. “Modern scientific criminology was apparently forgotten when the greatest crime in murder history broke,” wrote Reeve. “Practically all the painstaking scientific advance of modern times was either forgotten or bungled.”

The condemnation of local law enforcement was in telling contrast to the lavish praise bestowed on the unflappable, relentless, and crisply efficient agents of the federal government. The accumulation of forensic evidence that had convicted Hauptmann had been the work of federal employees far removed from the physical scene of the crime. Whether it was the lumber trail followed by the U.S. Forestry Service, the analysis of financial data by the Internal Revenue Service, or the tracking of gold certificates around New York by the Department of the Treasury, the expertise derived from Washington, D.C., not Trenton, New Jersey.

Firing up a publicity machine for media outlets ready to print its press releases verbatim, the FBI hogged the lion’s share of the glory for cracking the case. IRS and Treasury agents, who had done the grunt work and insisted, over Lindbergh’s initial objections, that the ransom money be catalogued and paid in gold certificates, seethed at the sight of J. Edgar Hoover taking credit for their work, but the T-men would have to get used to the G-men stealing the spotlight. “Every kidnapping case turned over to this division since enactment of the Federal kidnapping law in June 1932 has been solved,” Hoover assured citizens at regular intervals throughout the 1930s. It was his FBI, Hoover boasted, that “put the fear of God and the law into criminals.” Its reputation established, its integrity unassailable, its power seemingly limitless, the FBI, with Hoover at the reins, rode the Lindbergh case to a preeminence it has never really relinquished.

Not all institutions emerged from the Hauptmann trial with an enhanced reputation. Even before the jury in the Flemington courthouse pronounced Hauptmann guilty, politicians, jurists, and editorialists rendered a harsh verdict on the conduct of the media. “Every detail of the trial is photographed for the newsreels, reported on the radio, and described in the newspapers at such length that even the President’s message to Congress was relegated to second place in favor of the day’s proceedings,” wrote the New Republic, repulsed by the “sorry spectacle” that had unfolded in Flemington. The novelist Edna Ferber, owning up to her part in the sorry spectacle, expressed disgust at “the jammed aisles, the crowded corridors, the noise, the buzz, the idiot laughter, the revolting faces of those of us who are watching this affront to civilization.” The corrosive influence of the media on the dignified conduct of American jurisprudence was the consensus takeaway from the Hauptmann trial. “Judges should, following the early but abandoned effort of Justice Trenchard at Flemington, decline to permit cameramen to degrade the process of the law in the pursuit of their trade,” advised the New York Times. “Those news and newsreel photographers who attempt these things hereafter should be forcibly prevented.”

Prevented they were—not by force but by a code of professional conduct. In 1937, as a direct result of the media sensation surrounding the Hauptmann trial, the American Bar Association adopted a resolution that condemned photography and broadcasting in the courtroom. Added as Canon 35 to the ABA’s Code of Judicial Ethics, the resolution read:

Proceedings in court should be conducted with fitting dignity and decorum. The taking of photographs in the courtroom during sessions of the court and recesses between sessions, and broadcasting of court proceedings are calculated to detract from the essential dignity of the proceedings, degrade the court, and create misconceptions with respect thereto in the minds of the public, and should not be permitted

In 1956, the ABA prohibition was updated to include television. For decades, to the eternal gratitude of freelance sketch artists, Canon 35 kept cameras out of even the most headline-grabbing criminal trials. Not until 1982 would the ABA formally repeal the canon, not until the mid-1980s would state judges routinely permit television into court, and not until 1991 would enough courtrooms be wired to make Court TV a viable cable concept—gaining for television the right of coverage that the newsreels lost in Justice Trenchard’s courtroom in 1935.

By the mid-1990s, the march of television cameras into the courtroom seemed poised to penetrate every level of the American judiciary. Yet the intrusion halted at the federal level because of the media frenzy surrounding the only other plausible candidate for the trial of the twentieth century, the trial in 1995 of football great and Hertz pitchman O. J. Simpson for the murders of his former wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman. The gavel-to-gavel, wall-to-wall television coverage of every moment of the trial, supplemented by endless hours of on-air punditry from journalists and lawyers, accrued huge ratings for cable news stations and black-humor fodder for late-night comedians. Grandstanding attorneys, money-grubbing witnesses, a starstruck judge, and a shocking verdict of not guilty for a guilty- as-sin defendant, stopped cold the march of the medium into the highest courts in the land. Still invested in the majesty of the law, the federal judiciary took the sleazy reality show that was OJ-TV as a cautionary lesson. The federal courthouse remains one of the few zones in American life blocked off from the camera eye—so far.

The rules drawn up for Hollywood in the wake of the Lindbergh kidnapping also remained in place for decades. In 1934, with the establishment of the Production Code Administration, regulator-in-chief Joseph I. Breen was given full authority to enforce the Code’s edicts against kidnapping. When a kidnapped-themed scenario crossed his desk, Breen curtly pointed out that the film “was filled with details of crime in connection with kidnapping, the payment of ransom, etc. It appears therefore to be in violation of the Association’s regulations re ‘Crime in Motion Pictures.’ ” Breen’s advice to filmmakers was always the same: “We recommend that you withdraw your application for a Certificate of Approval.” Moreover, while the cinematic present was being patrolled, the cinematic past had to be erased. The troublesome kidnapped-themed films from the pre-Code era—Three on a Match, Okay, America!, The Mad Game, and Miss Fane’s Baby Is Stolen—received an imperious thumbs-down when submitted for rerelease under the Code.

For the next twenty years, Hollywood not only kept kidnapping off the screen but bequeathed the prohibition to television. In 1951, the National Association of Broadcasters Code of Programming Standards, in accord with its special responsibility to children, pledged to eliminate “references to kidnapping of children or threats to children.” The family-friendly medium of the 1950s no more wanted to give mothers nightmares than did Hollywood in the 1930s. In 1954, the Screen Writers Guild Bulletin reminded members, “With all [television] sponsors, kidnapping of a child is an absolute ‘NO!’” Actually, the kidnapping of a child on television wasn’t quite an absolute “NO!” Unlike the Production Code, the Television Code lacked an ironclad enforcement mechanism: barring a violation of the Federal Communications Act, what aired on television really was a gentleman’s agreement. Thus, on June 22, 1954, ABC’s prestigious and risk-taking anthology series U.S. Steel Hour telecast a live drama entitled “Fearful Decision.” Produced by the Theatre Guild and written by Cyril Hume and Richard Maibaum, the teleplay dramatized the desperate gambit by a millionaire father whose son is kidnapped: he refuses to pay $500,000 in ransom on the grounds that to accede to the demand would only encourage more kidnappings—and, the odds are, the boy is dead already anyway. “You know, up to now, there’s been a network taboo against kidnap stories,” actor Ralph Bellamy, who played the determined father, told a reporter during a break in rehearsal, “but this one is so different and handles the subject so intelligently, we didn’t have any trouble getting it okayed.” The critically praised teleplay was so popular it was reprised two weeks later for a second live broadcast.

Sensing a valuable property for the big screen, MGM purchased the film rights to “Fearful Decision”—and had its application for a Production Code seal turned down on the usual grounds that kidnapping was forbidden under the Code. MGM appealed the decision to the executive board of the Motion Picture Association of America in New York on the eminently reasonable grounds that denying theatrical exhibition to a motion picture that treated a theme already broadcast, twice, into the nation’s living rooms was absurd. The MPAA board agreed and overturned the PCA ruling “on technical grounds.”

Playing up the once-forbidden theme, the film version, released in January 1956, was given an exclamation point and retitled Ransom! “Never before has the motion screen been permitted to portray the story of a kidnapping!” blurbed the taglines, short on pre-Code memory. In the film, the eight- year-old son of a wealthy manufacturer is kidnapped. Referred to, but not depicted on screen, the method of the actual kidnapping is simplicity itself— no violence, no breaking and entering. In the safe-and-secure precincts of the Eisenhower era, a woman disguised as a nurse goes to the boy’s school and says she has come to bring him to his doctor. The school principal turns him over without question.

As the boy’s mother lurches from hysteria to catatonia, the father comes to a hard-nosed decision. Addressing the kidnappers over television, clutching the ransom money, he refuses to pay the $500,000 ransom demand so as not to continue the vicious cycle. “No pay off, no kidnap racket, no profit motive,” as a cynical reporter explains. The police chief alludes to the pertinent background. “You’ve seen it yourself,” he says, “the biggest men in this country openly making deals with kidnappers—and the voting public wouldn’t have it any other way—even though the child were dead right straight through from the beginning.” The father’s fearful decision is the right one: no ransom is paid, and the boy is returned unharmed.

On December 11, 1956, the Motion Picture Association of America officially ended the ban on kidnapping scenarios. “Kidnapping of children is now okay on condition the subject is handled with restraint and discretion and the child is returned unharmed,” stated the new policy. “This point is a hangover from a 30-year-old outburst [over] kidnapping based on the Lindbergh case,” explained Code chief Geoffrey Shurlock, Breen’s more lenient successor, after the PCA granted a Code seal to Compulsion (1959), a thinly veiled version of the Leopold and Loeb case. The kidnapping of a child, even if murdered, the nightmare of an earlier generation, would henceforth be fit subject matter for American entertainment.”

Copyright (c) 2020 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

THE BOOK’S OFFICIAL RELEASE DATE IS NOVEMBER 3, 2020.

Order Little Lindy is Kidnapped: how the Media Covered the Crime of the Century here