CFP – The Politics of Casting in Media Conference (online)

University of South Wales, 20-21 November 2021

Introduction

This blog piece explores the politics of casting in media and fandom. Certain casting stories are well documented: Henry Thomas’ audition for E.T. (1982) that brought Spielberg to tears, Denzel Washington taking roles that Harrison Ford won’t or can’t do, Jameela Jamil being cast in The Good Place (2016-20) with no acting experience, and how J.J. Abrams reached out to John Boyega for Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) after seeing him in Attack the Block (2011). These instances help perpetuate the mystique of stardom and/or the magic of Hollywood media-making. Such stories can also feed into the paratextual nexus surrounding a text, providing extra content that fans so often yearn for. For example, part of The Mandalorian (2019-20)extras sees a roundtable where Gina Carano discusses with her co-stars Pedro Pascal and Carl Weathers and executive producers Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni how she received a phone call (no audition) from Favreau offering her the role of Cara Dune; a job she would later be let go from due to her highly problematic social media commentary (Couch, 2021), potentially damaging to the brand image of Disney and Star Wars. Yet far from mystical, casting as a procedural practice is a cog in the media production machine that is shaped by, and shapes, wider political economies. As such, casting overwhelmingly ‘adheres to standardized codes, conventions, and expectations of the industry [surrounding race, gender, sexuality, and able bodies]’ (Warner, 2015: 34).

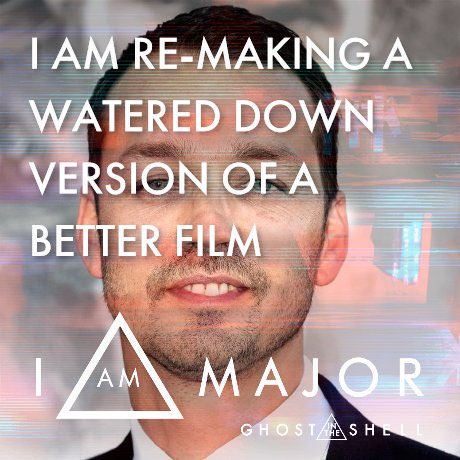

Moreover, fans develop strong attachments to their media objects and foster parasocial relationships with celebrities and actors, engaging with casting in particular ways. On the one hand, fans champion the stars who help furnish the storyworlds they love and with whom they can identify (e.g. Yodovich, 2020). On the other hand, fans, or indeed anti-fans, vehemently vocalise disdain for particular characters (e.g. Hills, 2003), casting changes or mis-castings (e.g. Fu, 2015), and the erasure of certain identities. The latter is particularly salient for audiences who themselves are mistreated and marginalised within society, such as people of colour (e.g. Warner, 2018; Rendell, 2019a). This also sees (anti-)fans protest casting decisions, demonstrated in the hijacking of Paramount’s viral marketing campaign for the remake of the cult classic Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell that rejected Scarlett Johansson as the film’s lead (Rendell, 2021). Yet whilst different fans, for different reasons, participate in casting discourses, this tends to centre on onscreen representations vis-a-vis actor embodiments or overt and highly publicised aspects of media industries. In this blog piece, we discuss what fans miss or elide when discussing casting and performing (anti-)fan identity and ruminate why this is so.

(L-R): Lil Rey Howery, Issa Rae, Tessa Thompson, Tiffany Haddish, Jerrod Carmichael, Lakeith Stanfield

James Rendell (JR): Forensic fandom is understood as audiences undertaking deep dives into media storyworlds; both the hyperdiegesis and the production cultures surrounding them (Mittell, 2009). Yet, in stressing this we can forget to examine what aspects of the story or creative processes do not get bored down into by fans and what this means. Likewise, the reformatting of media content may offer audiences a glimpse behind the curtain into the making of productions, which instils value into DVD/Blu-ray artefacts (Hills, 2007) and can reinforce production companies’ brand identities (McCulloch, 2015). However, certain practical tasks that have real world consequences for textual representations and the employment of creatives are obfuscated or completely absent. In both fan explorations and media formatting, casting-as-a-practice seems to suffer from such obscurity.

Kristen Warner (KW): Indeed. Many of the ways that fan labor processes the events surrounding their love objects are by deconstructing the official information shared with them by those “powers that be” who need to reinforce and maintain the brand relationship between the producers and audience and by identifying people who offer insider knowledge via gossip or firsthand experiences on set. By no means are either of these knowledge systems unuseful; on the contrary, savvy fans often can sort out the gristle from the meat and construct partial yet viable ideas of what is to come. However as you mention, certain aspects around production decisions such as casting and other types of employment are missed because of a lack of interest or investment in learning about the consequences of economics around their love objects. It is on the whole much less interesting to know that, for example, part of the reason that Fifty Shades of Grey’s Christian Grey was never going to be Robert Pattinson or Matt Bomer because the majority of the film’s budget was locked up in Universal Studios acquiring the rights to the book series. The two lead characters were almost inevitably going to be booked by up and coming actors because there was so little money left to hire known talent. Nevertheless, fan casting, that is the act of fans imaginatively speculating who they believe should be cast, functioned as a looming part of the excitement around the FSOG’s development.

JR: Yes, conversations surrounding casting can be a salient part of pre-textual fan discourse that can even feed in transformative work, such as fan art that depicts desired actors taking on the role of championed characters. Yet, I wonder about when casting is discursively avoided. I was struck by your discussion surrounding race and casting, where for ‘many industry professionals race is “heavy” and, for them, acts as a yoke around their neck rather than functioning as a beneficial and organic additive’ (Warner, 2018: 257). As you add, ‘the notion of race as heavy indicates an awareness on the part of many creative industry professionals that there is no simple fix with the colourblind casting of diverse bodies in a kind of “dipping white bodies in chocolate,” mode of hiring’ (ibid). I wonder if this notion of weight and weighted discussions can be extended to fan discourse. Fandoms have been praised as communities that provide political potential for outward facing citizenship (Jenkins, 2012; Jenkins and Shresthova, 2012), but this seems likely when debates or citizenry goals are aligned with championed media texts’ subtext or affective enjoyment. Likewise, the criticisms aimed at The Ghost in the Shell, Paramount, and Johansson resonate with general cult fan disdain for mainstream remakes of beloved fan objects; especially Hollywood remakes of cult media from other parts of the world (e.g. Hills, 2005). As such, Hollywood was an easy target as it is already Othered for many cult fans.

In comparison, for some fans to read against the affective grain and undertake critical engagement of their beloved fan objects or unpick the complexities of conglomerate media’s political economies may produce a somewhat dissonant mode of fan positioning or feel too much like ‘work’ with no obvious end goal. The ‘heaviness’ of certain critical readings or extra-textual knowledge, for example the racial politics of casting within mainstream media (Warner, 2016; Kim and Brunn-Bevel, 2020), may run counter to normative fan pleasures and not necessarily yield subcultural capital. In some instances, when these topics are raised online, they can be quickly shut down and the users chastised for being ‘too’ political that reinforces whiteness as both a textual and subcultural normative (e.g. Scodari, 1998; Young, 2014; Johnson, 2015).

KW: It is indeed a fascinating thing to observe fans try to hierarchize what aspects of fandom are for “fun” and which ones have political stakes. In my own experience of both being in a fandom, I am often surprised at how often the pleasure of belonging and a volume of content will prevent the necessary kinds of discourse needed to advance a fandom from hobbyists to aficionados. Years ago, when the popular recap site Television Without Pity still existed, I remember visiting to do a bit of preliminary research on how fans navigated the racial issues surrounding The Vampire Diaries. I was in a thread about the blindcast character Bonnie Bennett discussing how her poor treatment in the series was tied to her racial difference and one of the posters challenged me by suggesting that perhaps thinking too much about race is why there’s so little race on screen. And so with that, yes, I can easily see how too much thinking about the meta-levels that the love objects possess can be quickly dismissed in favor of pure and terribly unthoughtful positivity. That said, James, in your case study of Ghost in the Shell, the issue was that the casting so blatantly violated the peaceful stance of those fans that there was no other choice but to take up the political arms and strategize a response. A half-hearted attempt to cast someone of Asian descent would have more probably resulted favorably for the project among the fanbase. What’s more, in that case it is not even about the heaviness of race–or the lack thereof–but rather that the visual body does not match the original materials. While this certainly leads to conversations about who is considered bankable and how the answer is often not AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) folks, Ghost’s remedy could have been far simpler.

JR: In building off my previous point, if some fans avoid ‘heavy’ discourse it is also worth considering the weight of meme textuality. In my article (Rendell, 2021), memes serve as visual verifiers of the Ghost in the Shell remake’s inferiority and inauthenticity, where the combination of bitesize text and image provide the subcultural shorthand for the larger points anti-fans argue. This becomes nuanced when Asian, Asian American, and Eurasian users post selfies that simultaneously delegitimise the film and legitimises their own racialised identity as an act, I argue, of third space writing. Yet, whilst memes ‘image posts can support racial and civic discourse, memes might be read as shallow or superficial in their engagement compared to traditional political commentary’ (Rendell, 2019b: 109). Again, we can consider what the memes do not discuss. Notably, the film’s director Rupert Sanders, who up until GitS had only directed one other feature film: Snow White and the Huntsman (2012). Thus, he seems very much a director for hire, rather than an auteur/authorial figure, yet meme texts paint Sanders as such to be able to lay blame at his feet. Yet, none of the meme imagery names nor criticises any other professional/behind-the-camera personnel that were pivotal to the making of GitS. In keeping with this blog, this includes casting by Lucy Bevan and Liz Mullane – both of whom have worked on a number of big Hollywood blockbuster productions – as well as other staff members in the transnational casting department (see IMDB 2017). Likewise, the screenplay writers Jamie Moss, William Wheeler, and Ehren Kruger are not mentioned for their ‘inauthentic’ character (re)creation of Major Kusanagi. Also, the various producers who helped the remake’s financing get away unscathed including the executive producer Mitsuhisa Ishikawa, a producer of the original anime (1995) and its sequel Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004). Likewise, Mamoru Oshii has publicly defended Johansson playing the role of the lead he originally directed across the original two cult anime films (Sheperd, 2017). If meme rhetoric refuses the remake as part of cult/mainstream distinctions, Ishikawa’s involvement and Oshii’s support potentially destabilises this symbolic binary maintained by fans of the original film and, in the process, undermining anti-fan rhetoric. It also highlights how contemporary white washing, whilst historically tethered to Hollywood, is a transnational issue tied to the political economies of global corporations. Again, the international complexities that impact representations within GitS and beyond – certain meme sets visually cite other blockbuster films that tautologically groups these texts as indicative of Hollywood’s problems with race – are something not explored in anti-fan meme discourse. Thus, memes are perhaps a double-edge sword in that they can convey anti-fan affect and discourse simply, effectively, and powerfully given that the hijacking of the marketing campaign went viral. Yet, this simplicity can frame ‘industry talk’ in ways that render certain visible roles with more power, agency, and status than they might actually have, i.e. Sanders. Likewise, memes’ uncomplicatedness misses the intricacy and convolution of multinational media productions in myriad ways, such as engaging with other employees working on projects and the international financing of films.

KW: Indeed, this is such a crucial point to make and honestly saddens me when I think of the ways that some fandoms absolutely do their homework and follow the money appropriately. The very idea that they stopped at Sanders and did not notice that the Shanghai Film Group/Huahua Media, who promised to finance at least 25% of all Paramount Pictures movies over a three year period, in exchange for helping distribute and market their films in China, had no issue with Johansson in the lead is telling. That a Chinese company tasked with marketing and promoting films in China did not believe that an Asian lead was bankable is the CRUX of the conversation and it is wholly overlooked (Scwhartzel, 2017) not just by fans but by critics who quite frankly should know better. The mystery here is easily solvable and, yes, while certainly indicative of fans’ personal testaments of visibility via visual mediation, does render the memes plastic. If one were to consider that outside of the obligatory testing done to unsuccessfully placate cries of disenfranchisement from unionized AAPI actors, the financiers seem to never have had a plan to book an Asian actress for the part. The realization does not soften the blow of GITS pre-production decisions but it certainly allows for the kinds of logics that multinational media productions embody. As you mention, Sanders is far from an auteur, especially after contributing to the breakup of yet another fandoms forever couple, Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart. He is a director for hire and his hiring choices are very much contingent upon his producers tastes and desires. Thinking through those logics, the logics of bankability even at the expense of a Chinese film studio denying an opportunity to a Chinese actress is essential to fandoms functioning less as meme generators that result in plastic discourse and more as thoughtful, strategic players in this heightened producer/consumer environment.

Bibliography

Couch, A. 2021. ‘The Mandalorian’ Star Gina Carano Fired Amid Social Media Controversy. The Hollywood Reporter, 10th February. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/the-mandalorian-star-gina-carano-fired-amid-social-media-controversy

Fu, A.S. 2015. Fear of a black Spider-Man: racebending and the colour-line in superhero (re) casting. Journal of graphic novels and comics.6(3). pp.269-283.

Hills, M. 2003. Putting Away Childish Things: Jar Jar Binks and the “Virtual Star” as an Object of Fan Loathing. In Austin, T and Barker, M (eds.). Contemporary Hollywood Stardom. London: Arnold. pp.74–89.

Hills, M. 2005. ‘Ringing the Changes: Cult Distinctions and Cultural Differences in US Fans’ Readings of Japanese Horror Cinema.’ In McRoy. J. (ed) Japanese Horror Cinema. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. Pp:161-174.

Hills, M. 2007. ‘From the Box in the Corner to the Box Set on the Shelf: “TVIII” and the Cultural/textual Valorisations of DVD.’ New Review of Film and Television Studies. 5(1). pp: 41-60.

IMDB. 2017. Ghost in the Shell (2017): Full Cast and Crew. IMDB. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1219827/fullcredits?ref_=tt_cl_sm#cast

Jenkins, H. 2012. ‘“Cultural Acupuncture”: Fan Activism and the Harry Potter Alliance.’ Transformative Works and Cultures. Vol. 10. http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/305/259

Jenkins, H. and Shresthova, S. 2012. ‘Up, Up, and Away! The Power and Potential of Fan activism.’ Transformative Works and Culture. Vol.12. http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/435/305

Johnson, D.D. 2015. Misogynoir and Antiblack Racism: What The Walking Dead Teaches Us about the Limits of Speculative Fiction Fandom. Journal of Fandom Studies. 3(3): 259–75.

Kim, M. and Brunn-Bevel, R.J. 2020. ‘Political Economy and the Global-Local Nexus of Hollywood’. In Hughey, M.W. and González-Lesser, E. (eds). Racialized Media: The Design, Delivery, and Decoding of Race and Ethnicity. New York: New York University Press. Pp:21-40.

McCulloch, R. 2015. Whistle While You Work: Branding, Critical Reception and Pixar’s Production Culture. In Pearson. R. and Smith. A.N. (eds). Storytelling in the Media Convergence Age. Exploring Screen Narratives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp: 174-189.

Rendell, J. 2019a. Black (anti)fandom’s intersectional politicization of The Walking Dead as a transmedia franchise. Transformative Works and Cultures. 29. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2019.1477

Rendell, J. 2019b. “A picture is worth a thousand corpses: Audiences’ affective engagement with In the Flesh and The Walking Dead through online image practices.” Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies 16 (2): 88-117.

Rendell, J. 2021. ‘I am (not) major’: anti-fan memes of Paramount Pictures’ Ghost in the Shell marketing campaign. New Review of Film and Television Studies, pp.1-27.

Scodari, C. 1998. “No Politics Here”: Age and Gender in Soap Opera “Cyberfandom”. Women’s Studies in Communication. 21(2). Pp:168-187

Schwartzel, E. 2017. “Paramount Pictures Gets a $1 Billion Infusion from China.” The Wall Street Journal, 19th February. https://www.wsj.com/articles/paramount-pictures-gets-a-1-billion-infusion-from-china-1484868302

Sheperd, J. 2017. Ghost in the Shell: Original director Mamoru Oshii defends Scarlett Johansson casting. Independent 26th March. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/ghost-shell-original-director-mamoru-oshii-scarlett-johansson-casting-whitewashing-a7650461.html

Warner, K.J. 2015. The Cultural Politics of Colorblind TV Casting. London: Routledge.

Warner, K.J. 2016. Strategies for Success? Navigating Hollywood’s “Postracial” Labor Practices. In Curtin, M and Sanson, K (eds). Precarious Creativity: Global Media, Local Labor. Oakland. University of California Press. pp. 172-185.

Warner, K.J. 2018. The emergence of the Iris West Defense Squad. In Click, M.A and Scott, S (eds). The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom. London: Routledge. Pp.253-261.

Yodovich, N. 2020. “Finally, we get to play the doctor”: feminist female fans’ reactions to the first female Doctor Who. Feminist Media Studies. 20(8). Pp.1243-1258.

Young, H. 2014. Race in Online Fantasy Fandom: Whiteness on Westeros.org. Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies. 28(5). pp:737-747