Guest Editor Maria San Filippo

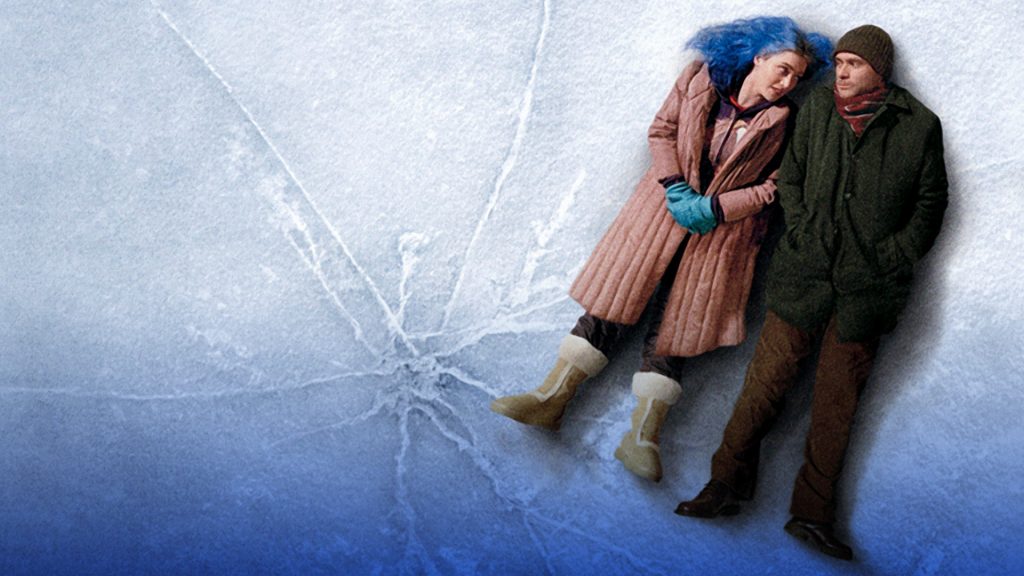

Introduction: Radical rom-com: not an oxymoron

EXCERPT: In contemplating what that final destination may be, we should keep in mind that rom-com’s devaluation (read: ghettoization) is also attributable – recalling Ruby Rich’s characterization – to the genre’s ‘built-in optimism.’ In conjoining ‘romance’ with ‘comedy,’ the genre’s creators and audiences imagine a potential for human connection through love and laughter. In some fundamental sense, this is a radical vision – one founded on a valuing of collectivity over individualism, a faith that the unknowable other might just be knowable after all, and a commitment to opening eyes alongside hearts. Certainly such a perspective runs the risk of being undermined by utopianism or, alternatively, tainted by insularity, as many a decidedly un-radical rom-com falls back on idealized representations and retrograde fantasies. But such regression is not a foregone conclusion, and thus neither is ‘radical rom-com’ an oxymoron.

Articles

Evidence to the contrary: matrimony & legal interventionism in silent divorce comedies

By Leslie H. Abramson

EXCERPT: Captivated by the vagaries of romance, American silent cinema was smitten from the outset with the narrative possibilities of not only attraction but the gamut of ensuing legal entanglements. Divorce and near-divorce comedies appeared in cinema as early as the turn of the century, contrary to their prevailing historicization. Moreover, focusing on the catalysts, processes, emotional turbulence, and romantic fantasies of divorce even among loving spouses, key silent comedies incriminate the law as a central agent in instigating and facilitating the couple’s disunion. This essay examines how Why Mrs. Jones Got a Divorce (1900), Getting Evidence (1906), and Max Wants a Divorce (1917) indict the modern legal system’s seductively broadened possibilities for divorce via modern methodologies and technologies for capturing attraction and licentiousness. These silent comedies pass judgment on the overriding appeal of fingerprints, the detective camera, and the private investigator, as well as other forms of legal documentation. The essay considers early divorce films’ association with silent cinema’s own weddedness to institutional codes and cinema’s commentary on its formal capacity to document the inconstancies of romance. Ultimately, insofar as intoxication with documentation rather than the spouse foregrounds the detriments of establishing actionable legal evidence, these divorce comedies implicate the law’s own capacity for unfaithfulness to a more perfect union.

Romantic comedy and the virtues of predictability

By Kyle Stevens

EXCERPT: While cinematic narratives are often evaluated and enjoyed in terms of their ability to captivate through suspense and revelation, in this essay, I mount a defense of narrative predictability. I take the genre of romantic comedy, arguably the most critically derided for its formulaic nature, as a case study, arguing that not only are there virtues to predictability but that the negative values that have been attached to it are often masculinist and politically suspect. More specifically, through a close reading of Nelson Lyon’s 1971 film The Telephone Book, I consider what romantic comedy shares with pornography, another genre that trades on the knowledge – evident from the start – that characters will, in the end, come together.

The awkward truth: failure to romance and the art of decoupling in the films of Hong Sang-soo

By Sueyoung Park-Primiano

EXCERPT: Hong Sang-soo’s films are famous for their persistent exploration of failed personal relationships. Hong’s obsessive passion for baring the truth about men and women in contemporary South Korea drives his experiments in narration, minimalist aesthetic, and improvisational style. Hong’s films are the antidote to syrupy date films; stripped of romance, even the occasional meet-cute scenes quickly sour and expire. Sex scenes are awkward and passionless, every chance encounter leading to drunken folly and disillusionment, and rarely do characters actually evolve. It is striking that Hong stubbornly refuses to inject any sentimentality into the meetings of men and women; and yet he appears to be under some compulsion to revisit these same stories again and again. This article approaches Hong’s work as an update and revision of the classical romantic comedy. It prioritizes Hong’s candid look at human weaknesses and insecurities and how he seeks to dismantle any idealized vision of two perfect strangers coming together happily. By bracketing Hong’s films as a deconstruction of the long-standing traditions that mythologize true love, the article identifies the dialogic relationship of these films to the romantic comedy genre, and interprets their idiosyncratic structure and style as an explicit critique of modern love.

Romantic female friendships as resistance: subversive web series in the United States and India

By Molly Bandonis & Namrata Rele Sathe

EXCERPT: The current representative wave of romantic female friendships (Girls, Broad City, Insecure) in the United States owes a great deal to the web series. The online platform bypasses conventions of the romantic comedy, which prioritize heterosexual romance over female relationships. This article seeks to bring two geographies (United States and India) into conversation with one another via a textual analysis of two such web series: Brown Girls (US) and Ladies Room (India). These stories of female friendship explore the unique concerns of urban female identity, sexuality, and solidarity. A central question we address in this textual dialogue is how these representations subvert and critically engage their respective political climates of neoconservatism. Brown Girls and Ladies Room move away from prioritizing heteronormative relationships reflects the transcultural disillusionment with the ideology of containment that defines the genre of romantic comedy. The acceptance of the romantic female friendship narrative within the mainstream thus fosters new critiques of old illusions of monogamous coupling, feminine duty, and heteronormative subjectivities.

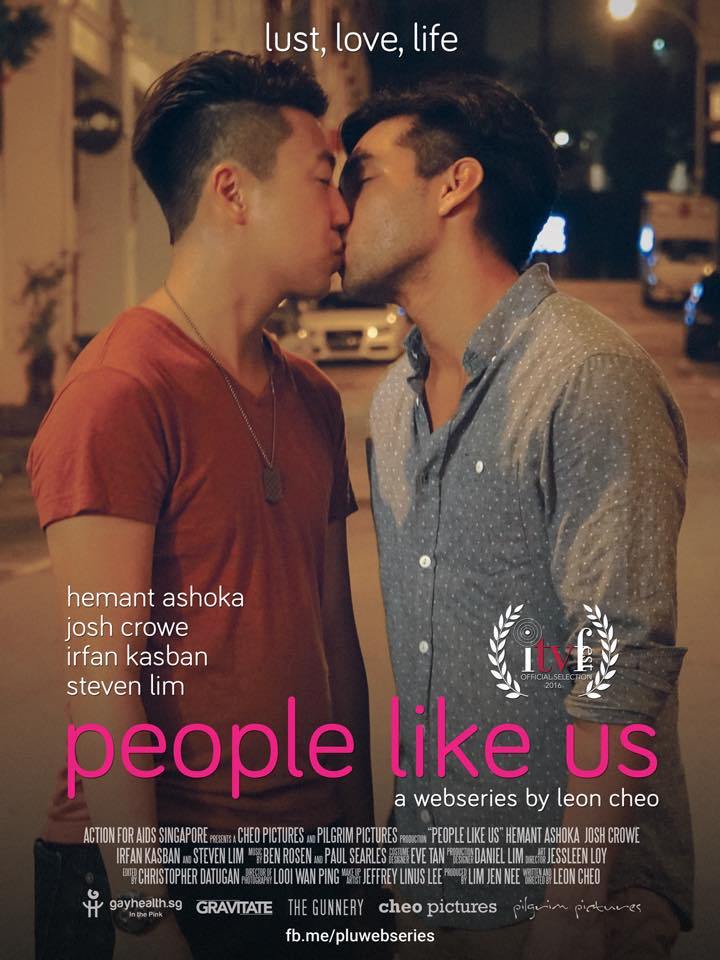

Rom-com without romonormativity, gays without homonormativity: examining the People Like Us web series

By Eve Ng

EXCERPT: This article discusses the Singaporean web series People Like Us (Leon Cheo, 2016) as a text with characteristics of a romantic comedy that also challenges many generic conventions. In terms of production and distribution, the web series format enables content that might otherwise encounter funding or censorship challenges. With respect to content, People Like Us has two important distinctions. First, while depicting gay men’s pursuit of romance in often lighthearted ways, People Like Us is not what I term ‘romonormative,’ i.e. it does not privilege monogamous romantic relationships or downplay same-sex eroticism. The series also encodes a distinct Singaporeanness without inscribing homonormative or homonationalist discourses, instead presenting different modes of gay men’s intimacies as comprising a queerly specific Singapore. As such, People Like Us’s production and narrative characteristics exemplify new evolutions for the rom-com genre.

“Money can’t buy me love”: radical right-wing populism in French romantic comedies of the 2010s

By Mary Harrod

EXCERPT: This article surveys developments in the French romantic comedy of the 2010s from a cultural studies perspective. Specifically, it considers how the particularities identifiable in the French genre following its emergence in the 1990s and consolidation by the end of the 2000s have evolved during the next decade. It argues that the most striking new trend comprises a more domestically circumscribed orbit for the genre, with notably fewer export successes, paralleled by the increased prominence of nationalistically inflected and/or otherwise broadly retreatist themes, notably in relation to ‘globalizing’ conformist (neo-liberal) values. These traits manifest themselves through elements such as explicit celebrations of French culture, especially that of the northern French provinces that are the historical heartland of the right; obsessive representations and validations of heterosexual family structures, including through homophobic elements; a marked accentuation of bromance and other misogynistic elements in the genre; and a parodic if not mocking attitude towards generic and cultural values coded as North American – albeit one typically embedded in layers of ‘self-reflexive’ postmodern irony. I argue that this last tendency, constituting one of the complexities of the hybrid French genre à l’américaine, is useful for interrogating the very concept of radical ideology – and its antithesis, conformity – for their different meanings in diverse geo-cultural contexts.