By William J. Simmons

Introduction by William J. Simmons

Drive

Moonbeams, frightened and indifferent,

trickle down and mingle with headlights

and turn red,

bright and undiluted,

like a rose offset by

snow that has yet to touch the ground.

This imaginary world

floats on the LA River and

I watch it escape from me,

flow and drive away.

I’m always more concerned with

what must pass me by

than what light I can hold,

here, in these hands, which emit

a crackle of leather-upon-leather.

When did I see him, you first?

Then, walking in the snow,

saying I’m sorry in the snow,

trying to get fucked in the snow,

with the darkness belied by

sunny boxed wine and

a crimson-grey cigarette that had yet to be pressed into skin.

No penetration, only yet another

divulging disappointment and more

summers spent in Cape Cod, not on holiday but because

you live there.

Gripping sounds transform into the silence of

watching a handsome young man relentlessly,

surreptitiously watch ice skating on the TV behind me.

(Regret makes me a Modern Girl)

To be seen invisibly

on an empty Boston road,

on the Red Line to Braintree,

on a walk to buy a box cutter,

stumbling upon nothing,

slapping kind faces,

longing, being pursued on the cold street, knowing, aching to be held at gunpoint,

crying, feeling crushed by another mouth.

Then a cineplex, footsteps to it and footsteps back.

Some changes in between.

All at once, one last gasp,

a choked and choking howl, just to say:

(I hear it through my strangling fingers)

“I might have loved you in return if only you’d given me just a little more time.”

The words of a debtor speeding off into the sunset.

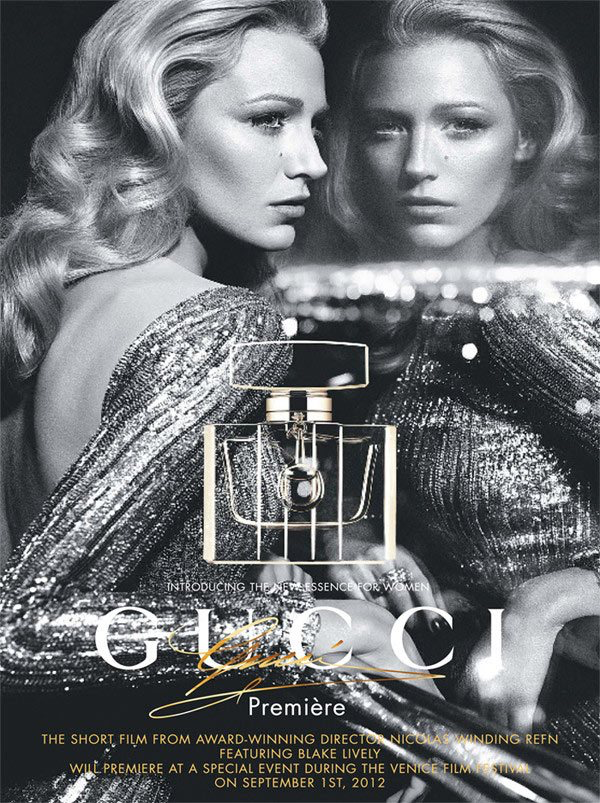

Interview with Nicolas Winding Refn

The following interview was conducted by William J. Simmons (WJS) with Nicolas Winding Refn (NWR) and is structured as a Q & A. The transcript was edited lightly for clarity.

WJS: When I think about your work, all of your films cross genres. There are certainly some horror and exploitation hallmarks in The Neon Demon, for instance, but it’s also a melodrama. It’s also a “women’s film.” or whatever the term is. To what degree were you thinking about, for instance, the B-movies and exploitation movies, that you’ve cited before that are compiled in the book The Act of Seeing, which you created with Alan Jones?

NWR: Actually, I was making that book while I was writing the film. I’m not really like a walking encyclopedia of film. I don’t really know a lot of movies. My introduction to film really came through television because I was born in Copenhagen and my mother and my stepfather moved to Manhattan when I was eight years old. And in Copenhagen at that time, there was only the state channel and they had maybe a 20-minute children’s program once every day if you were lucky. It probably involves some eastern European dolls or something like that or an even more politically correct version of Sesame Street. So, I discovered television and it wasn’t so much what was playing, but that I could change the channel and something else would appear. When I think back, this is really what started my interest in film. But it wasn’t so much the films. It was just a belief that I could control them. I could control the emotions by flicking from one emotion to another emotion, from a movie or a TV show to a commercial. I’ve always loved this idea of being able to go from one emotion, then with the click experience something completely different. You create a nonlinear linear format. It’s like poetry in a way. There is no real narrative in the traditional sense. It’s just a flow of emotions.

The book came about because of Jimmy McDonough. He had been working on Times Square in New York in the 70s and had been a big part of that scene. I’d always been interested in anything that was perverse, probably for more of a voyeuristic point of view. And I was a big club kid in New York in the 80s. You know, I ran with the whole Michael Alig crew and I remember going to Danceteria. I remember when Palladium opened as a nightclub. When Jimmy asked me if I wanted to buy his poster collection, I was like, yeah, sure, why not? Boxes arrived with like 1000 posters and my wife was like, really?

I started looking at them and I didn’t know any of the movies, but I found the images very fascinating and the titles and all of what they promised. I was like, either I’m going to throw them out, or I’m going to make the most expensive poster book ever made. I decided to make the book. We went to LA and I had gotten The Neon Demon financed without a script. I was in some kind of a limbo land. I mean, I had come up with this concept of wanting to do a movie about beauty and the obsession of beauty and what it must be like to be envious of beauty. I mean, I wasn’t born beautiful, but I have a wife who was, and I have children who are very beautiful. Ironically enough, my eldest daughter had her first modeling shoot yesterday.

I’d come up with this concept [of beauty] and I had hired Polly Stenham, who was this very young playwright based in London. I worked with her on this concept I had and then brought in another writer, Mary Laws. I was trying to become the 16-year-old girl that is in every man. What was the odyssey going to be like? And every time I was creatively stuck, I would go through the book. I would use the book every night or whenever I was stuck creatively to go through to react to these sensational promises of sin that a lot of these films would promise.

And so, in a way, [The Act of Seeing] was conceived as I was conceiving the film. Every time I would get creatively stuck at night or if I was inspired, I would always use the book as a visual reference of what kind of kaleidoscope I wanted The Neon Demon to be. And I wanted it to be a kaleidoscope of emotions. But the core of it was beauty because it’s something that is distasteful in many ways. And yet it’s something we are so obsessed with and have been and will continue to be more and more. And it will dominate our lives more because of the digital revolution, because with the world of the digital, perception is how we are introduced to each other. Do you have an image? That is how we define ourselves and how we want to be defined by others. And there’s a glorification and the celebration of the narcissist, the individualistic idea that narcissism is a virtue.

Aleister Crowley believed that if you didn’t give into your sins, you are actually being sinful. I always found that very interesting, especially when it comes to beauty because there is a part of us that indulges in perception and that very much is a world that is dominated by women. It’s in our methodological understanding. We think men were strong, women were beautiful. Whether that’s wrong or right, that’s not for me to judge, but that’s how we would read fairy tales. You know, that’s how you would read into Grimm’s fairy tales and how I would read them for my own children. Beauty is so much more than just what you look like. It’s what can be done with it. It’s the power of it. It’s the influence. It’s many things. It’s the only thing in a way. And I think that part of you giving into that perversion of indulging in something that is essentially sinful, it’s just very intoxicating.

WJS: That is a really interesting way to enter the film. I largely focus on gay and feminist art. You’ve said in several interviews about several different projects, but specifically about The Neon Demon, that this is not a political work. By way of sort of maybe digging deeper into that question, what would you consider to be a political work of film and how is your work different even though many people would say, well, this must be some sort of commentary on feminism?

NWR: Well, I think that it’s normal human behavior to want answers or to label whatever you experience. Especially nowadays, it’s the norm because the faster something is defined, the quicker you can be consumed, defined and forgotten. And I think for me, everything can become political and anything can become sociological. You can read anything you want into whatever is there. I always say political films are more made for its time where I make films for the future.

Political films deal with predominantly themes of the past in terms of a political ideology: what does the filmmaker politically believe in, what’s the purpose of it and what is the agenda and what is to be defined? Because politics needs a definition. Poetry on the other hand is free of that because it’s not based on an ideology of how the world needs to function. It’s about human behavior, which is futuristic.

WJS: Is it fair to say to you maybe that form is more interesting to you than content?

NWR: I think depending on the film, form is, at least for me, what intrigues me. But you know, you’re a product of where you’ve come from. I mean, I grew up in New York in the late seventies, early eighties and part of that movement of that time was conceptual art—the idea that the concept was artistry. You didn’t necessarily need to have craftsmanship if you had a vision because the vision was the concept and that you were the canvas. Yourself was an extension within that. So that’s why I always say I can only make films about myself essentially because I am the only thing that I can look within. Because I like fetishization, I make films about what arouses me and because I make fantasy. At the end of the day I make artificial reality. I don’t make documentaries. You know, love and hate are the same thing creatively. It’s just a flip of a coin.

WJS: How do you take something that is very much about you and put it into a space where other people are going to project onto it, where the audience might or form a different kind of relationship? If you’re coming to it from a very individualistic standpoint, how do you transfer that individual experience into something that any other person could relate to in a productive way, as in a melodrama?

NWR: Well, that’s the billion-dollar question. I don’t know how to answer that because I don’t have a formula and I hope to God I never find it, because then it loses its sincerity. I always believe in being sincere in what you create. It’s essential. But it’s also frightening because it’s an equivalent of taking your clothes off in public and then asking everyone to look at you. And so I don’t know if there is an answer to that. It’s like liquid. It just kind of flows through your fingers and then it just evaporates. The experience stays on and that’s how I always look at it. It flows through you whether you’re thirsty or not, or desire liquid, it’s still essential for your existence because if you don’t have liquid, you don’t have life. But I can only do what I do and then if it is sincere then it will always have a heartbeat.

WJS: What is your relationship to irony, which is often seen as a hallmark for cinema deemed interesting?

NWR: I mean, look, anything is valid. I’ve never made anything with the intention of making something ironic. The chief enemy of creativity is good taste. Irony for me is almost like a filter that you can impose on what you do because you are afraid of being naked. But there is a strange masochistic satisfaction in nudity to be exposed to other people, especially if you don’t know them, because the idea of creativity is to draw attention to oneself. Your creativity is an extension of you. The desire is to be seen. There’s always a strong sense of exhibitionism, but you need to own that. And if that makes you uncomfortable you put an ironic filter on your work. But it almost makes it all in good taste and then it becomes the enemy.

WJS: I think that that definitely comes through in The Neon Demon where, in a certain sense, it’s a film about belief. I think that’s interesting too in terms of archetypes or even clichés, if one wants to use that term.

NWR: I think what’s great about clichés is that they work. That’s why it’s a cliché. There is this misunderstanding that a cliché is viewed as something negative. It only is if it’s felt without imagination. The lack of imagination sterilizes the cliché, but if the imagination that is infused is gigantic, the cliché becomes an asset. But there’s this strange belittlement of clichés that seems to be invoked right now, which is ironic because we’re getting more and more conservative in our views.

The archetypes of the Elle Fanning character as either innocence or ultimate evil, it’s up for interpretation. She’s a cliché of both, but there is no answer because if you’re given an answer then there’s nothing to react to. So, she is the enigma and in a way she is the female version of Driver from Drive. And Driver was a version of One Eye from Valhalla Rising. She continued in Only God Forgives with the lieutenant and in each stage she evolved. So, when Elle played it was primal; it was ancient. And when Ryan Gosling played him, it was of your time; it was of your fantasy. There was something imaginary about him. Then in Only God Forgives, he was futuristic. The Elle Fanning character, she was the female version of all three male characters. She was the past, the present, and the future. At the same time she was pure innocence and yet she was all ultimate evil. She was an antidote and she was a virus. She was essentially an emotion in its core.

The enigma of her was that she was both of the spectrum. She was the same side of a coin. That makes her a cliché on both sides, but there’s no definition to her. There’s no explanation to her. Once you don’t explain, it’s natural for us to start looking for the answer because we are accustomed to get through information, we get clarity. We get control, and through control we then understand it and consume it and forget about it.

WJS: At some point at the press conference at Cannes, Elle mentioned that the script was substantially changed. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about that.

NWR: I like the unknown, so I was very open. I didn’t really know how this film was going to end, even though I had an ending, I knew it was not going to end like that. And it’s been like that on all the films I’ve made since Bronson really. Even the Pusher trilogy was a little bit like that, but once Bronson came in, it really became the concept. And so we got The Neon Demon. The idea that she was just the innocent girl coming to the city to be a model was the big starting point. But then it was two weeks into the shoots that I think, “You should be the evil one.” And it was like painting, again, with people. Community, we were all painters painting together, and they would just consume and suck out everything from everyone. Then Jena Malone was such a good actress and her character was surely supposed to die, so I decided not to kill her. Then I was like, “I want you to become a witch now and you will be speaking to the moon.” Those kinds of things are how we continue to evolve and evolve and change.

WJS: How do you do something that’s at once familiar but also leaving room for there to be a surprise, or for the narrative to shift in an unexpected way?

NWR: I don’t know how to answer that, but I will say that I always believe simplicity, which again, strangely enough, a lot of people find very provocative, just like they find silence very provocative. But I guess it’s so many things overcompensate in complexity and noise to hide the fact that people that are making it have all their clothes on.

WJS: As a final question, I have to ask—you’ve got the gay art historian here! At the Cannes press conference, you made a passing comment about Drive and homoeroticism and I was wondering if you could talk about that a little bit more.

NWR: I always find old-fashioned heterosexuality to be very dull in fantasy, and I think that with the movie like Drive the fetishization of Ryan’s physique and his aura really is so erotic that it becomes exciting to admire. It’s all very normal for women to admire other women’s physique and to look at them and so forth. But for men, it’s still, at least for heterosexual men, it’s very uncomfortable.

What’s great in fantasy is that it can be components that are a form of an extension. For Drive, the idea behind it was that I wanted to make it about a man and drives around in a car at night listening to pop music, because that’s his emotional relief. But art is feminism in a way. It’s all raw emotions and so I always say the more femininely the character’s portrayed, the more masculine it becomes because he crossed the border of normal heterosexual sexuality.

I love women. The female body is for me the most glorified piece of art, but I understand the excitement of having both sexualities within you and living out your desires. The love story between Driver and Irene is pure teenage love, but the Driver is half man, half woman in a way. The homoeroticism comes across because it is the way that I photograph him and the way that he is perceived. It both caters to both sexes equally and that makes him the ultimate man, the ultimate hero. And then in The Neon Demon, that homoeroticism of Jena Malone’s character, and the extent that she lives at her fantasies to death is in a way the ultimat, erotic act. Death and sex with death because death has no gender really. And so it was a living sexual celebration through both experiences, whether it was the Driver character or through Ryan Gosling or through Jena Malone.I dedicated The Neon Demon to my wife Liv because the whole film, everything I do in many ways, is about her. Drive was about the love that I have for her. What I would do, my fantasy illusions of my youth, the idea of protecting her. With The Neon Demon, it was more like I worship her and I’m envious of her as a human being, of everything she possesses, especially her beauty, because I can only fantasize about being beautiful.

Part 2 forthcoming in early 2021