Reviewed by Ken Stewart

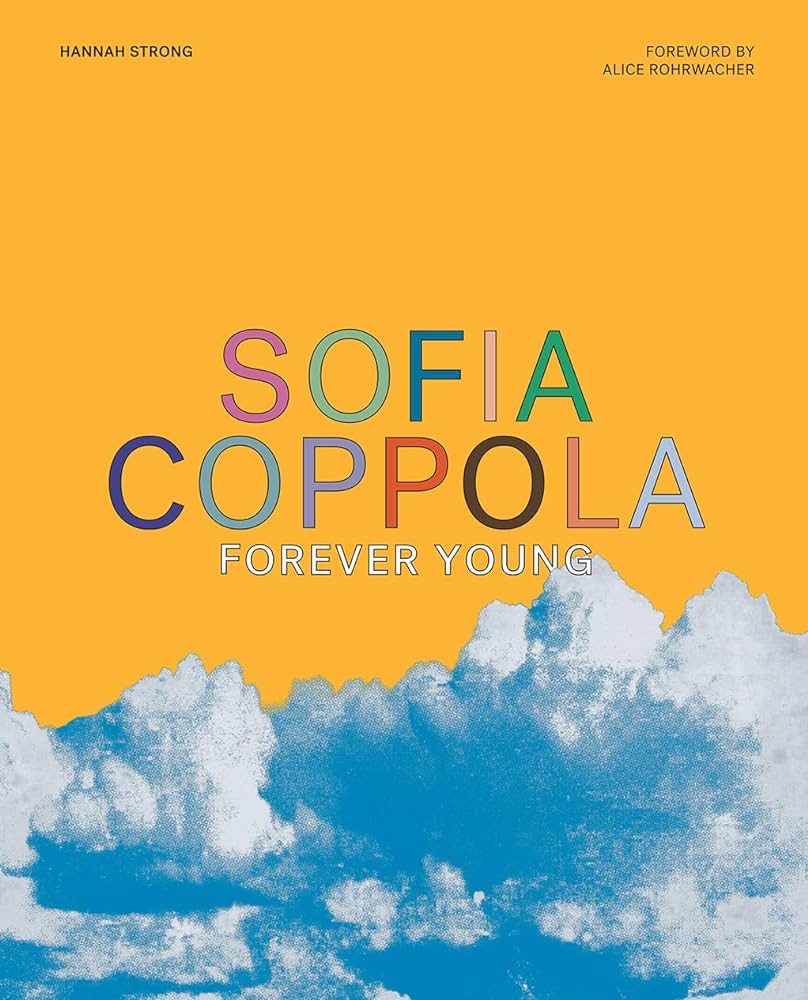

Upon first impression, Hannah Strong’s Sofia Coppola: Forever Young, a thick hardcover compilation of the titular subject’s film and media career, is gorgeous. The playful block lettering in a rainbow of pastels spells the famous director’s name, overlaid onto a collage of pale blue pixelated clouds digitally cut and pasted over an orange-yellow book cover. Clearly, this isn’t a regular book on filmic analysis and male auteurs; this is a cool book on filmic analysis and a very powerful female auteur: Sofia Coppola.

Upon further inspection, the interior cover of hot/pale/millennial pink cybernetic abstractions match Strong’s fashionable dress, evident in her author’s photo on the final page. The design of Strong’s tome is reminiscent of flipping through a coveted Vogue September issue or Seventeen magazine of yesteryear. Her book on Coppola is a gloriously tactile perusal through glossy pages, replete with stunning full color stills and behind-the-scenes photos from every Coppola film aside from her most recent film, Priscilla (2023).

Forever Young’s aesthetic appeal does not stop at its impressive design. The Table of Contents acts as a guide through the collage of information that Strong has collected on Coppola throughout her research. Traveling to the back of the book, the Production Notes, Index and Bibliography make this visual and textual analysis a living document. And as a reader, I frequently found myself flipping between the front material and the references on box office successes, themes of femininity and allusions to other adored films. These corroborating resources of information added a sense of richness to my newfound understanding of Coppola’s work.

Strong takes a uniquely modern, journalistic approach to the synthesis of Coppola’s public life and art through analog and digital resources. Throughout her book, she engages with the films themselves via DVD bonus features, interviews over the past two decades from magazines like Vogue, social media selections from YouTube and Spotify, reviews from more literary journals such as The Paris Review, and culture columns culled from The New York Times.

At its core, Forever Young’s structure of information is told in a circular, nonlinear fashion—almost like a well-informed diary or fairytale. Beginning with both filmmaker Alice Rohrwacher’s forward (in both the original Italian and an English translation), entitled “Sofia’s Garden,” the reader is immediately immersed in a realm where female directors create a hazy daydream world to cope with the severe confines of femininity.

While Rohrwacher’s adoration of Coppola is a guarded, almost mystical abstraction of reverence of Coppola’s first film, The Virgin Suicides (1999), Strong’s connection to Coppola’s earliest feature film is vivid and striking: she begins her introduction boldly by offering the reader a trusting look into her adolescent inner world: “The first time I wanted to kill myself I was thirteen years old” (11).

From here, Strong uses the remainder of her introduction to orient her critical analysis of Coppola’s filmic work through her personal experiences as a female viewer who felt her adolescent angst was misunderstood by the outside world. These feelings of deep turmoil were uniquely recognized by Coppola, a goddess giving materiality to the ephemerality of passionate emotion juxtaposed against physical stagnation. Strong contends that the crucial viewpoint of the teenage girl has been missing from writing on Coppola’s work.

Strong echoes the heroine’s journey in the remainder of her introduction, spinning the tale of a girl named Sofia, a Taurus, born the daughter of famed Hollywood directors: an aggressively masculine figure in her father Francis Ford and a ubiquitously observational temperament in her mother Eleanor. Forced into a failed acting career as a teenager by her father, Sofia drifted between artistic pursuits throughout the rest of her adolescence—fashion, music and photography (at the behest of her mother)—collecting a group of sparkling friends along the way, including Zoe Cassavetes, Spike Jonze and Marc Jacobs. Compelling details emerge in these early explorations of the moments that Sofia begins to find her footing as a budding visual artist in text-heavy sections entitled “Music Videos, Commercial Work and Short Films.”

Once Sofia [the girl] finds her visual voice, Strong, acting as a narrator, guides the reader through the rest of her life and directorial work as Coppola [the woman] through a creative layout emphasizing imagery. Coppola’s narrative features are grouped thematically around the ideas of feminine youth identified by Strong, rather than in order of actual creation. Each section is announced with another unique digital collage layered beneath the theme’s title: “Innocence & Violence” peers into The Virgin Suicides and The Beguiled (2017); “Celebrity & Excess” covers the aesthetic frills of Marie Antoinette (2006), The Bling Ring (2013) and A Very Murray Christmas (2015); “Fathers & Daughters” reckons with Somewhere (2010) and On The Rocks (2020); and finally, “Love & Loneliness” drifts into a concluding examination of Lost In Translation (2003). Each theme concludes with a section titled “Inspirations” and reviews a selection of films by other filmmakers that are clearly influential or directly alluded to in Coppola’s work, such as In The Mood For Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000), Paper Moon (Peter Bogdanovich, 1973) and Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975).

Each feature film vignette is front-loaded with several pages of photographs, usually outnumbering the length of the text by multiple pages. While many film analysis books are text-heavy, Strong allows the reader to engage with the visual source material directly. As she notes, “[Coppola] has always been more interested in allowing audiences to develop their own understanding of her films than dictating where and when significance exists” (110). Strong’s emphasis on imagery and feeling mirrors Coppola’s communication style, making this retelling of her narrative portfolio achingly visceral.

Strong offers captions for each photograph presented at the beginning of the film’s analysis, a combination of production notes related to each frame, or references and allusions to other works identified by Coppola in various interviews that Strong sourced in her research. The layout of these photographs is like a collage in itself, with photos either taking up an entire page for emphasis, like the many stills from Lost In Translation, or photos being methodically placed in small or unusual spaces on a blank white page, which is apparent in the visual layout for her more controversial follow-up feature, Marie Antoinette.

Arriving at the films’ textual descriptions, Strong includes the year released, runtime, budget and box office numbers as a header template before diving into her analysis of each work, mentioning everything from the ideation, pre-production, production and distribution processes of the film. Strong illuminates Coppola’s creative processing of youth and girlhood through her journalistic compilation; however, because she heavily identifies with Coppola’s stories and perspectives, she does not directly address any instances of blatant privilege or racial microaggressions portrayed in Coppola’s work, as pointed out by some of Coppola’s critics. Nonetheless, Strong’s exploration into Coppola is pioneering in the ways it explores white feminism in popular culture: all women are still at a loss to the patriarchy, but by beginning to acknowledge the work of women of privilege, we can work towards celebrating the stories of all.

After a beautiful foray into the core themes of Coppola’s auteur arsenal, Strong completes Coppola’s journey of artistic transcendence by turning her focus to another primary source: interviews with Coppola’s longtime collaborators such as actress Kirsten Dunst, Jean-Benoît Dunckel from the band Air and editor Sarah Flack. A significant, heart-stopping quote is delivered in Strong’s interview with Dunst, an early Coppola collaborator starring in The Virgin Suicides and Marie Antoinette. Dunst reflects on her time as a teenage girl coming up in late 1990s Hollywood under the watchful eye of the male gaze. Because of her experiences working with Coppola, Dunst states, “Well, Sofia thinks I’m pretty. I felt like the coolest girl thinks I’m cool, so I’m good” (245). Through Strong’s comfort as an interviewer, the reader sees Coppola for what critics are unable to see through the eyes of her “garden flowers,” as Rohrwacher might call them: a friendly visionary with excellent taste in fashion and music, a soft spoken and sharp communicator, a curator of unseen experiences and deep intuition, a role model and very cool girl.

With her breathtaking and multilayered curation of Forever Young: Sofia Coppola, Strong collects an array of ephemera—images, interviews, popular cultural references, privilege, girlhood, love, disdain, color, collage—in support of Coppola as an auteur, a woman and a mosaic of an individual. Strong’s work serves as an act of humanity, fighting the patriarchal structures that often withhold powerful women from existing in the public eye. Likewise, Coppola uses her perspective, her access and her care for the quiet parts of girlhood to illuminate the passionate and misunderstood paradox of the female transformation: the heroine’s journey. Sofia Coppola’s “garden” is a place where girl-dreamers like Dunst, Strong and myself can rest our heads on the grass amidst the flowers, staring at the clouds in raucous peace.