In advance of our forthcoming Special Issue, “That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore: A Critical Exploration of Joker”

A roundtable discussion featuring guest editor Sean Redmond (Deakin University) and contributors Caroline Bainbridge (Roehampton University); Jesús Jiménez-Varea, Alberto Hermida, and Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla (University of Seville); Misha Kavka (University of Amsterdam), Mark Kerins (Southern Methodist University), and Ernest Mathijs (University of British Columbia).

As I compose this lead-in to the roundtable discussion that follows, Joe Biden has just been inaugurated the 46th President of the United States. As more than 74 million Americans made shockingly clear, it could have gone drastically differently. This introduction is infinitely easier to write given the outcome of the election, alarmingly close as it was. As Sean Redmond’s introduction to his guest edited special issue, forthcoming this March, spells out, Joker is a film as much about our present as about the past in which it’s set. When I received Redmond’s proposal in 2019, though I felt sure that the topic was all too important, my initial sense of Joker’s (at best) ambivalent and (at worst) reckless approach in registering the real-life nightmare playing out on the national stage made me wary of welcoming that nightmare’s uncanny likeness into our pages.

As 2020 would come to show, I didn’t know the half of it. While this made my anticipation of the impending issue – as with all things in the last many months – all the more anxious, so too has it become only more apparent with each new crisis, injustice, uprising, and – now – insurrection, how presciently Joker took our cultural temperature and issued a distress signal that, not unlike those sounded shortly thereafter by immunologists and #BLM/Antifa activists alike, was drowned out in the din of rancorous discord, panic, and suppression that followed.

Looking back, I’m heartened by the efforts that Redmond and his global cohort of co-contributors devoted in this most challenging year to tracking that distress signal, to carefully and judiciously appraising such an intractable work as Joker, training clear eyes and open minds on its cadences such that we now might hear more acutely and forcefully its call of alarm. The exhaustion wrought by 2020 makes me all the more grateful for their rigorous intellectual labor on our behalf, as does the reminder a year in to my tenure as NRFTS editor of my good fortune at finding myself empowered to usher into the cultural conversation such enlivening exchanges and perceptive insights as those below and in the special issue to follow. Like any work of art, Joker is a living document necessarily subject to reassessment — hence our having conceived this roundtable — and faced with the fallout of 2020, it’s clear there’s a great more to say, and to do. If ever a film has sounded a blaring wake-up call for a new decade, Joker is it.

MARIA SAN FILIPPO, NEW REVIEW OF FILM AND TELEVISION STUDIES EDITOR

NRFTS: What, for you, made Joker feel urgent to write about?

Sean Redmond:

I think there were two almost simultaneous reasons: watching Joker filled me with both a sense of dread and desire, as if the film had flashed its oblique consciousness across the scars and tissue damage of this viewer; and reading the critical commentary pointed to a film that was both an ‘event’ and compass point for the collisions and dislocations in the social world. It reeked of Trump and austerity, and yet its ideologies and ‘senses’ undermined any simple or singular dominant reading. That the film divided both viewers and critics confirmed for me that this would be a film that ‘mattered’, that needed greater understanding, and which therefore needed assessing through a special edition.

Jesús Jiménez-Varea, Alberto Hermida, and Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla:

Mostly, it was Todd Phillips’s revisionist take on the eponymous character, carefully crafted to manipulate the viewers’ emotions and propitiate their empathy, while also focusing on current real-world social issues. All of it wrapped in a highly appealing and culturally resonant aesthetics, powerfully captained by Joaquin Phoenix’s stunning performance.

Caroline Bainbridge:

My feeling when watching the film for the first time at the cinema was that it was the most timely thing I had seen in quite a while – it seemed to have its finger on the pulse of shifts that I was sensing were happening all around, bringing the message to a crescendo and conveying the urgency of the entanglement of mental health with aspects of identity at just the moment when identity politics and the culture wars seemed to be pushing the global agenda into worrying and frightening new domains – or, perhaps they are not so new, just resurgent in a novel form… I thought the film makers had cleverly bolted the sensibilities in question to the superhero genre, intelligently showcasing the film’s complex commentary on the state of the world and the states of mind it engenders by harnessing it to a genre with mass appeal.

Ernest Mathijs:

For me, it was the combination of ‘rushed judgement’ (and a self-sustained media panic, in which media almost seemed to compete to be the most alarmist), and the burst of both symptomatic interpretations and narrow interpretations that left out audiences who wanted to elaborate and have a conversation about wider implications or aspects of the film’s reception.

Misha Kavka:

The film has a mesmerising ambivalence that speaks to our cataclysmic era suffused by constant exhortations to hope, smile, be kind, care, etc. (an ambivalence that has only intensified, and hence become more urgent, under pandemic conditions). The film’s ambivalence is aesthetic (it’s a beautiful film about a horrible subject, as distilled in the scenes of Joker dancing), political/moral (it’s a compassionate film about the rise of collective violence), and affective (the reviewers all hated or loved it, with no in-between, while my own experience was of having seen a very moving, elegiac film about the justification for male violence).

Sean Redmond:

When I sent out the cfp I had close to 70 abstracts submitted. These abstracts took me across numerous academic disciplines and approaches and methods. It was clear that across the arts and humanities, Joker had indeed struck a major chord.

When making the selections I wanted to narrate a sort of journey: where we moved from space, place, to bodies and music. Each article would address a key theme (a major chord) but would at the same time lead to the next: its ‘minor chord’ would become the next article’s major chord, so to speak. Joker would haunt each article, sometimes a saviour, a radical, a figure of chaos; and sometimes seen in the service of othering and neoliberal resurrection dreams and fantasies…

My own chapter sees the film through the lens of loneliness: Arthur is a carrier of what it feels like to be lonely. And yet his loneliness is also joyous and murderous, and so the folds and flows of the lonely imagination are also set in tension. Joker is marked by his loneliness and goes on to kill with it.

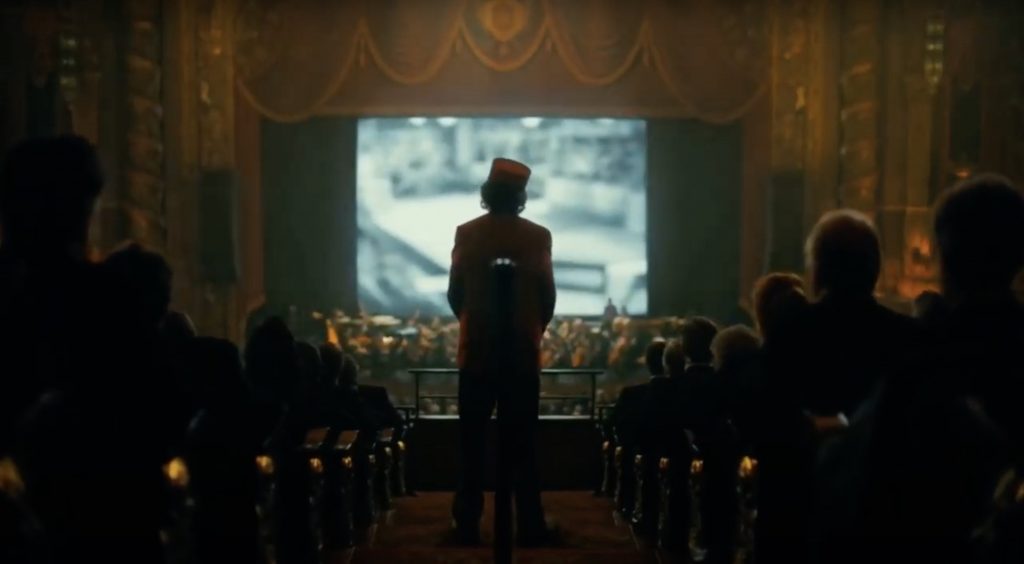

When Arthur first ‘dances’ as Joker in the film – a scene set in a dilapidated public toilet – one has a haptic, fully sensorial experience. The delusional, deadly Joker dances for and to you: a hypnotic, soft, but invasive dance of dread and desire…. It is one of those lasting movie ‘impressions’ that I still feel on my body as I recall the scene…(fig. 1).

NRFTS: Why do you think the superhero narrative has become the dominant mode of contemporary commercial cinema, and what impact do you feel that’s had on our culture?

Misha Kavka:

Interestingly, not so long ago I would have said that the answer to this question is simple: the superhero narrative assures us that the world is divisible into simple right and wrong/heroes and villains, and it locates us, via identification, in a place of insuperable power within this world – always on the side of the right and good. But in recent years, the genre has begun to fracture, thus also fracturing the inevitable moral and physical success of the (super)hero through grim tonality (e.g., The Dark Knight), the heroes’ mortality (e.g. Avengers: Infinity War), or simply satire (e.g. Thor Ragnarok). This greater complexity has allowed the superhero narrative to develop from genre film to, as you say, the ‘dominant mode’ of contemporary cinema. At the same time, this fracturing makes evident what has been the creeping impact of the superhero narrative all along: namely, that as audiences are encouraged to feel the moral and material righteousness of (their own) power through these figures, the superhero film has a more or less direct connection to the impassioned political bifurcation between ‘liberal’ left and ‘alt’ right that so many nations, as well as the entire social media-verse, are currently experiencing. It took Joker, though, to make this connection explicit.

Ernest Mathijs:

I am actually not sure if the superhero narrative is all that different from ‘hero’ narratives in general – in that they are a sign of mono-mythical storytelling, against which I notice a rise in frustration from storytellers and audiences alike. I guess you could say that with the convergence in media-conglomerates there is a convergence in storytelling perspectives.

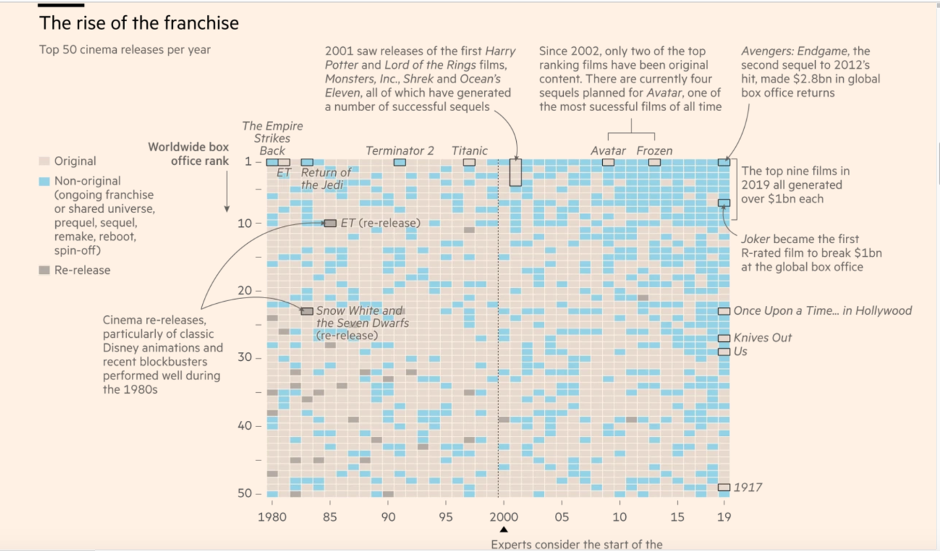

Figure 2 below, taken from a January 2020 article from The Financial Times, shows that ‘sequels, remakes, franchises’ are more popular than ever. It is an evolution you can see as alongside the rise of comic book superheroes, but I am not sure the fact that the heroes are more ‘super’ than before is a driving force in this evolution.

Jesús Jiménez-Varea, Alberto Hermida, and Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla:

This question opens the doors to many possible paths of reflection and argumentation.From a technical and technological perspective, in the last couple of decades, cinema and television have reached the point at which they can generally offer convincing live/CGI-action portrayals of the most physical and fantastic aspects of the hyperbolic exploits routinely found in the pictures of the comics medium that gave birth to the genre.

Contextually, the larger-than-life nature of superheroes (and supervillains) may be speaking to social, cultural, and ideological preoccupations related to such phenomena as posthumanity, post-truth, global trauma (namely post-9/11 and presumably the current COVID situation), along with a general need for savior figures in times of crisis that may well have favored this ever-increasing interest in superheroes in media more massively consumed than comics.

Also, it is pertinent to pay special attention to the crossroad of the superhero narrative and the franchise strategy in which we can find the superhero franchises as developed in the cinematic medium, particularly the MCU and the DCU. Of course, only the latter did enjoy the spotlight in the previous cinematic superhero crazes, starting with Donner’s Superman and Burton’s Batman respectively. However, during the present and still strong superhero boom, it is the Marvel characters that invariably become box-office sensations, while their ‘Distinguished Competitor’ does not seem to keep the pace (though, to be fair, this situation is pretty much reversed in television). We could speculate that the MCU makers have found a most valuable blueprint for their strategy in the original comic-book universe as designed by Stan Lee, arguably more noteworthy as an intuitive marketer and implementer of synergies between titles than as a writer, strictly speaking. Whatever psychological and/or social anxieties this fascination with shared and inter-connected universes responds to, its huge potential for profit from the perspective of the entertainment industry is already leading to many other attempts to develop similar multi-franchise projects, often with dissimilar results.

All in all, arguably, media audiences have already become so familiar with superhero conventions that the genre is now ready to work as a general framework in which a variety of modes and effects can be played, including comedy, horror or character studies (like Joker), to name just a few possibilities already explored.

Caroline Bainbridge:

I write about this in my article, citing psychoanalytic work on the psychological function of both the superhero and the supervillain. Such characters offer us ways of processing aspects of experience linked to fantasies of authority, gender, control, the law, power, and oppression – all themes that seem to resonate with the shifting sands of ideology since 2008 in particular. The collapse of established pillars of ideological authority and control in the last decade has been linked to the emergence of ‘toxic’ forms of (cis, white) masculinity such that this trope is now commonplace in popular culture. I think the superhero genre allows viewers (and readers and creatives) to process what it might mean to live with the uncertainties created by ideological fissures and to bear the unknown dimensions of feeling and a sense of self as the reality of their impact comes to be understood.

Sean Redmond:

Mythically, superheroes have always had a hold on the popular imagination: everyman made superhuman. However, the machinery of the transmedia, transnational, entertainment industries produce ‘product’ that can be sold across multiple markets. The superhero franchise perfectly fits these new forms of vertical and horizontal integration.

I am not sure there is one superhero narrative but many, and these narratives are not ‘contained’ or ‘complete’ but speak to wider political and social issues, and to the origin myths they come from. That is to say a film such as Black Panther is not the same as Captain America. Spider-Man (2002) can be read against the grain of 9/11, while TV series The Boys can be read against the alt-right fascism of Trump. When Homelander masturbates over New York City [while repeating “I can do anything I want”] at the end of season two, he cums in the image of Trump (fig. 3).

Mark Kerins:

Perhaps the biggest shift in studio feature filmmaking over the past few decades has been the move away from thinking of most movies as individual creations and instead shifting toward ‘universes’ and franchises. Obviously franchises and sequels have existed for a long time, but as the costs of making and marketing a major release have increased and the stakes of each film thus higher, studios seem increasingly reluctant to take ‘risks’ on new intellectual property when they can instead do a sequel/remake/spinoff that capitalizes on audience familiarity. The success of Marvel’s MCU has inspired other studios to try to copycat it (with limited success) through things like Warner’s DCEU, Paramount’s Transformers universe, and Universal’s ‘monster’ universe. Given this, some filmmakers are finding ways to explore the stories and themes they want in these existing sandboxes – so you get something like Joker which is really a portrait of a mentally ill protagonist that through using a couple key names and design details is ‘placed’ in the Batman world and thus gets the attendant marketing and attention. It’s easy to imagine an indie version of this film (or a studio version as an ‘Oscar bait prestige picture’ in an earlier era) being made without the Joker/Batman connection; it’s hard to imagine that version, however well done, getting the marketing push or achieving the box office success of Joker.

NRFTS: How do you understand the newfound turn towards superhero franchises centering on the villains (thinking of Suicide Squad, Joker, and now the forthcoming Loki series)?

Misha Kavka:

I think of this in terms of the ‘fracturing’ of the originary simplistic moral order of the superhero universe, as I discussed in my previous answer. In terms of genre, we could lean on Thomas Schatz’s work to recognise that film genre is dynamic and needs to change in order to stay relevant (and meaningful). In this case, though, the genre has not just remained relevant but become fully dominant, which suggests that the ‘villainous turn’, first to an expansion of the role and most recently to the villain-hero, speaks to a certain kind of widespread social grievance that understands the villain not as a bad guy, but rather as a disenfranchised guy – someone, that is, like the Joker, but also like so many audience members who feel that the world owes them something, which has not (yet) been delivered.

Ernest Mathijs:

I think the receptions of The Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal, Dexter, and countless zombie and vampire films have shown that villainy is a safe bet. Villains are seen by audiences as more complex (why are they the way they are?) and invite more sophisticated interpretation (or, more checks within a reaction). You see that in the reception of Joker (if you look past the media panic mentioned above).

Jesús Jiménez-Varea, Alberto Hermida, and Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla:

This seems to be part of a wider interest in what have come to be known as “bad protagonists” in popular narratives, which is not really unprecedented as attested by the attractiveness of Milton’s Satan, Gothic villains, and Byronic antiheroes in the past, an let’s not forget that the first shared cinematic universe was built around the Universal studios versions of classic monsters such as Dracula, the Frankenstein’s monster and the Wolf-Man. In more recent times, it was just a matter of time that the proliferation of popular narratives (both factual and fictional) around very questionable main characters would spread to superhero franchises.

From the subversive attitude of trickster figures such as Loki or the Joker himself to the overt evil of psychopaths like, again, the Joker (in most iterations), supervillains probably appeal to a range of appetencies in the audience, including a certain degree of identification with flawed characters (versus impossibly noble superheroes) or a morbid curiosity toward the vicarious experience of taking a walk on the wild side.

Sean Redmond:

When I teach sci-fi and horror to my undergraduate students I give them the binary option of whom they most like or are ‘attracted to’: Clarice or Hannibal; Frankenstein or the monster; Terminator or John/Sarah Conner etc. They very often majorly favor the villain. This may be to do with the power of transgression, the unwieldly nature of the taboo; the ‘excess’ that defines their characters, but it also points towards the moral and ethical uncertainty that sits at the heart of culture and social life.

Caroline Bainbridge:

As [I responded] above, I think this speaks volumes about the ideological context and the collapse of faith in a system of patriarchal authority that leaves some men feeling out of place and out of time. Villainy and its appeal are everywhere – we just have to look at the popularity of the antihero protagonist in TV drama to see further examples of this. Jungian analysts might argue that this points to the persistence of our shadow side, and suggest that the ‘darker’ elements of human nature are brought to the fore in the context of the collapse of faith and trust that we have seen taking root in the western ideological setting of late. I’m most interested in what this reveals about the pleasures we take from witnessing painful and traumatic experience – is this because it provides a sense of relief and release from the on-going individualised and personal everyday traumatic lives inflected by a late capitalist system that erodes notions of community and humanity? Does it show us how meaningful cultural experience has become for a sense of survival and resilience in the face of ever increasing processes of mediatisation? Does ‘escapism’ into fantasy and archetypes paradoxically allow us to contemplate what remains of selfhood, and what aspects of self-experience remain unscathed by mediatization and the logic of capital? For me, the entanglement of technologization and mediatization with selfhood is one of the most pressing questions of our time. The unconscious psychological aspects of human experience need urgent attention in my view.

NRFTS: While the majority of viewers saw Joker in theatres, it now seems “day and date” releases are likely to be the new norm — how do you think this will affect the cultural impact of movies like Joker?

Misha Kavka:

I think this is actually a question about streaming platforms and, rather like the cable revolution of the 90s, the extent to which streamed releases will break up what was once a fairly coherent movie-going socius. If, as I suspect, ‘day and date’ releases will severely diminish the impact of opening weekend buzz, then this will likely reduce the audience that sees a film in the ‘water cooler’ period of 2-4 weeks within release, as well as reducing the breadth of the audience that goes to see a film. In turn, this is likely to reduce cultural impact of films like Joker, even if – perhaps – the exhibition profits remain the same.

Jesús Jiménez-Varea, Alberto Hermida, and Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla:

Most probably, this phenomenon will alter the whole landscape of the film industry profoundly, but it is difficult to forecast its effect on the cultural impact of movies like Joker in particular. Actually, the on-demand availability of a wide library of movies should contribute to the viewer’s immersive experience in multi-franchise universes, but Joker is somewhere between the standalone film (at least so far) and an unequivocal place within an intricate web of serial narratives and alternate versions.

Ernest Mathijs:

I am super curious about this evolution. I love theatres and the sense of occasion and ‘event’ that comes with (and with festivals, retrospectives, double-bills, …or other forms of ‘live’ curation), and I worry about losing a sense of ‘happening’ if that goes away. Joker‘s release at Venice was a significant moment. But so was its extended run, and so was its longer life on social media (even prior to its release), and so was its streaming run, and … in other words: if we are serious about studying film receptions we need to look beyond the ‘immediate splash’.

If we look at reception trajectories over periods longer than the three weeks of a box-office release (or its equivalent on home screens, namely the ‘top 10s’ or ‘popular in your region’, that streaming services use) then the longer tails of this change in distribution are not yet visible. Audience reactions and engagement with the released text may (or may not) need to switch perspectives (for instance, how do we look at ‘cohorts’ of reception?)

Mark Kerins:

The pandemic basically accelerated the move to ‘Day and Date’ releases that was already underway; Wonder Woman 1984 is a perfect example of what we will see more of in the future. Setting aside whether this is good or bad for the movie industry as a whole, in terms of cultural impact it seems likely to push in two different directions. On the one hand, it becomes even harder for any one property/movie to be a ‘break out’ success when it won’t have the same theatrical box office or cultural currency of something that smashes records, draws sell-out crowds, etc. Even if a film reaches a massive audience through home viewing/streaming, it’s usually impossible to get accurate details from the streaming services on how many people watched something, in what time frame, etc. And for those watching at home, it’s less likely to feel the need to watch something the day of its release as opposed to a week or several weeks later – it’s the paradox of something being available every night making you less likely to feel any urgency to watch it. On the flip side, it does seem possible that for the few movies that really do can cultural traction and feel like ‘everyone’s talking about it,’ they can reach more people more quickly. Those who can’t afford to go to the movie theatre, or don’t have a babysitter to stay home with the kids, or whatever, can still watch a movie at home and join in the conversation that previously may have been limited to those who made it to the theatre opening weekend. So it seems likely we’ll see less films really rise to the top as things everyone is talking about, but those few that do may actually be more widely seen than in past years.

It also could make people choosier about what they’re willing to pay to see ‘on the big screen’. It’ll be those rare movies both crafted to really take advantage of theatrical space and which attain a level of quality and cultural relevancy to get people to be willing to go out and pay to see them in the theatre. The entire pandemic I’ve only gone to the theatre once, and it was to see Tenet (four weeks into its run, but still) because I knew that was a movie that was designed for the big screen and would play significantly differently in the theatre than at home.

NRFTS: How do you think Joker looks from today’s vantage point, given the events of 2020?

SEAN REDMOND:

In one clear sense Joker seems one of the most prescient films ever made: ‘rioters’ and ‘looters’ donned Arthur’s Joker mask as America fell apart. However, as I write in my introduction to the special issue, the film’s allusions and references show us that what it fears and desires stretches back in time, into the long night of the birth of neoliberalism. This is a film that shows us the full arc of the politics of the last 40 years.

Misha Kavka:

As I was answering the first question, it struck me that the deep-seated ambivalence of Joker, exposing an even more deep-seated cultural and political bifurcation, has become more relevant due to the events of 2020. Conspiracy theories – whether related to Trump or COVID-19 or both – are cutting into mainstream media use, as people express grievances, on behalf of themselves and others, against some imagined ‘deep state’ of would-be heroes that has long done them wrong. These are the grievances that Joker gives voice and violent expression to, and, if anything, the situation became only more bifurcated, and more grievous, in 2020.

Jesús Jiménez-Varea, Alberto Hermida, and Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla:

In 2020 we have been witnesses to real scenes of social revolts and streets on fire that strongly resemble those in Joker, as well as blatant exercises of oppression, discrimination, and power abuse that may well justify the kind of violent reaction against the system inspired by Arthur Fleck in the movie. Additionally, the Covid lockdown and the fear of contagion along with the proliferation of conspiracy theories related to the same pandemics as well as the US elections may have put many millions in a situation not so different from the miserable circumstances of Arthur just before becoming the Joker, confined in his flat, living mostly through screen devices, and struggling to hold his grasp on a reality in which the barriers between the truth and delusions (and blatant lies) have been blurrier than ever.

Caroline Bainbridge:

Gosh, this is hard to answer… In many ways, it foreshadows the acute and lingering collapse of all that we most take for granted in the contemporary way of life, and heightens our reliance on technologized states of being and relatedness in ways that had not really been imagined as a real (tangible) possibility for many people at the level of everyday life. The epidemic of loneliness and the sharp increase in reported struggles with mental health have intensified the feelings on show in Joker, while these have also been diversified across boundaries of social class, race, sex, gender, embodied experience and so on. I don’t want to suggest that Joker can in any way been seen as a harbinger of our experiences in 2020, but, in hindsight, it certainly acts as a useful cipher through which to read the writing that was clearly on the wall.

Breaking Down Joker

Violence, Loneliness, Tragedy

Edited By Sean Redmond

Will be available December 31, 2021