By Nora Stone

Once, the 2013 documentary Let the Fire Burn was available to stream with a Netflix subscription. Then it was gone, removed from the mainstream subscription streaming service. Now, to watch the film, you must hunt it down: subscribe to niche streaming service OVID.tv, sign in to Kanopy with your library card, pay to rent it from AppleTV. Granted, these options mean the documentary remains available to the viewing public. But it resides on a tier of accessibility out of reach—and out of mind—for many people. Relegation to the less-traveled corners of the streaming landscape presents a problem for documentary filmmakers trying to reach a broad public with their work.

The fate of Let the Fire Burn has been repeated again and again over the last decade. Where once the mainstream streamers appeared as saviors for documentary, bringing them more attention and making them more widely accessible than ever, that hope has crested. Major streaming services’ priorities have changed; they no longer value the independent documentaries that used to fill their catalog.

To better understand how Netflix and other general audience streaming services have dumped documentaries, let us turn to this particular case study. Let the Fire Burn is a documentary about the MOVE bombing, a standoff between Philadelphia police and a radical Black group called MOVE in May 1985.

Director Jason Osder, professor of Media and Public Affairs at the George Washington University, spent 12 years making Let the Fire Burn. The Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program and the Independent Television Service (ITVS) supported the production of Let the Fire Burn. As two of the most prestigious institutions in American documentary, their recognition and support means that a documentary has been heavily vetted by industry experts. Sundance and ITVS support give a film legitimacy and a launchpad for success.

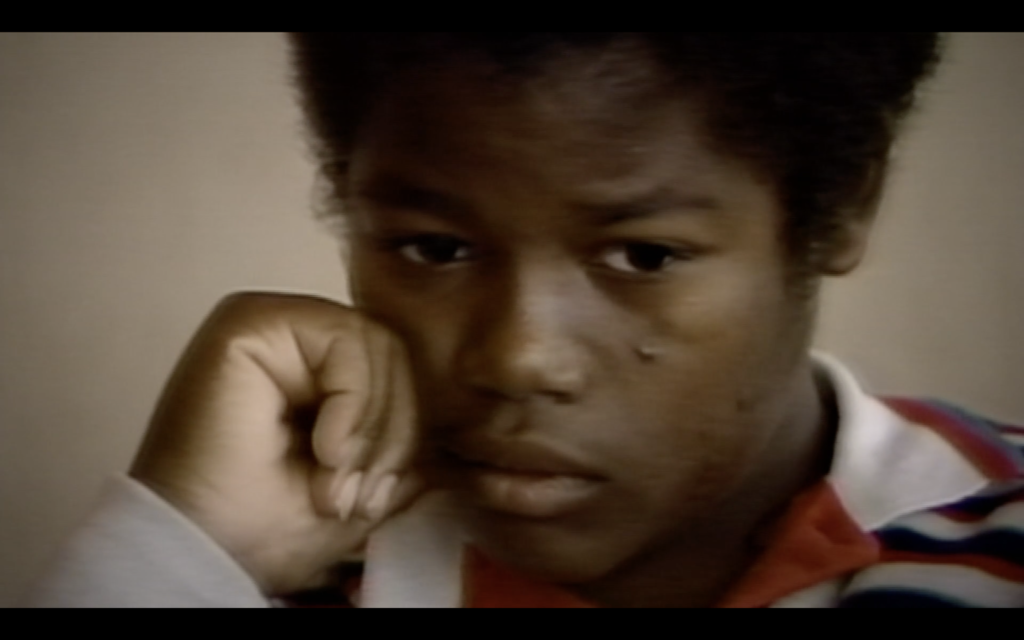

Indeed, Let the Fire Burn premiered at the 2013 Tribeca Film Festival, where it won awards for Best Editing in a Documentary Feature and Best New Documentary Director.1 But I was lucky enough to see the film even earlier, when it was “sneaked” at the True/False Film Festival, in Columbia, MO. I was transfixed. The subject matter was shocking—a police siege of a back-to-nature Black revolutionary group in Philadelphia gone wrong. While authorities had meant to evict the MOVE group from a rowhouse in the Osage Avenue neighborhood, the fire they caused ended up burning down 61 homes and killing 11 members of MOVE, including 5 children.

This tragic event has extraordinary immediacy and ambiguity in Let the Fire Burn because of Osder’s approach. The film is made up solely of archival footage, culled from home movies, television news coverage, depositions and public hearings.2 By using archival footage, Osder lets us experience the event firsthand, rather than through distant recollections. The film builds narrative tension as it ratchets up to the 1985 siege. We feel the strength of MOVE members’ convictions and the frustration of their neighbors. We see police footage of MOVE’s prior run-ins with law enforcement. We begin to understand how all parties would have felt it necessary to stand their ground in a confrontation. Once the siege begins, we are embedded with TV reporters on the ground. We feel their fear as they run and crouch behind their news vans to escape the gunfire the police let loose on the MOVE compound. We hear onlookers describe the scene as a “warzone.” We are present as commissioners interrogate former members of MOVE, the police chief, and district attorney in the aftermath of the disaster.

Inherent to this narrative tension is a productive ambiguity toward all historical actors. Osder does not paint MOVE members as innocent victims of police violence, nor does he dismiss their revolutionary aims as foolish. Rather, he shows the impossible situation that MOVE, the neighbors they terrorized, and the city authorities were in. This conflict animates Let the Fire Burn into an excellent historical thriller, as heart-pounding and intimate as Heat.

Let the Fire Burn earned high praise following its official premiere at Tribeca, and it played at numerous film festivals around the world. Zeitgeist Films, an independent distribution company with a rich experience in distributing documentary films, acquired Let the Fire Burn. Zeitgeist opened the film in theaters at Film Forum in New York and NuArt in Los Angeles in fall 2013. In 2014, it was awarded the Truer Than Fiction Award at the Independent Spirit Awards. Finally, it was broadcast on PBS’s Independent Lens on May 12, 2014, and it became available to stream on Netflix around the same time. By all measures, Let the Fire Burn had a successful distribution and exhibition. It reached more people than most documentary films by being acquired by Zeitgeist and playing theatrically. Being programmed on Independent Lens meant it was broadcast to viewers by PBS stations across the country. Being available on the most popular subscription video-on-demand service, Netflix, meant it had the potential to reach Netflix’s 57 million subscribers in the United States.3

But by the time Netflix licensed Let the Fire Burn for streaming, the service was already pivoting to a new strategy: producing its own content. This pivot to vertical integration would result in Netflix’s own critically lauded series, like House of Cards and Stranger Things. But it meant that licensing independent documentaries was no longer a priority for the company. Even in documentary, Netflix has focused on proprietary series and a few branded Netflix Originals, not on licensing a high volume of individual films.

The benefit of producing its own content is that Netflix owns these movies and series in perpetuity, rather than needing to negotiate license fees from their owners. This became important as the streaming wars escalated. Studio conglomerates built their own siloes of content, like Disney+ and Peacock, rather than licensing films and series to a general audience streaming service like Netflix.

The result is that Netflix did not renew its license for Let the Fire Burn. The film quietly disappeared from the service in 2016.4 The same fate befell many other documentary films, even those with the highest pedigree and the most heart-pounding pacing. It is now rare to find politically incisive or formally inventive documentaries on Netflix and other mainstream streaming services.

This brief distribution case study shows the precarity of media access, especially for social and historical documentary. A place on a major streaming service is not guaranteed. It can be revoked by multinational media conglomerates simply because business strategy changes. The result is that audiences’ access to the hidden histories and cultural treasures within documentary films is endangered.

One way independent distribution companies and collectives have responded to this crisis of access is by building alternative streaming sites like OVID and Projectr. I explore the creation and curation of these sites in the fallout from streaming vertical integration in my article for NRFTS, “Beyond the Algorithm: Curating a Streaming Library for Documentaries.” With simple app-building tools, and a large repository of documentary and other independent films, these small sites are able to match the look and functionality of the mega streaming services. For a more detailed account of documentary films’ place in the media ecosystem, see my recently-published book, How Documentaries Went Mainstream: A History, 1960-2022.

Read more about How Documentaries Went Mainstream: A History, 1960-2022 on the Oxford University Press website.

Order online at https://global.oup.com/academic with promotion code AAFLYG6 to save 30%!

Read the free chapter here. Free to read until 18 September 2023.

Read Ezra Winton’s review in issue 21.4 (Winter 2023) of New Review of Film and Television Studies.

Nora Stone’s article “Beyond the Algorithm: Curating a Streaming Library for Documentaries” is forthcoming in issue 22.4 (Winter 2024) of New Review of Film and Television Studies.

Sign up for NRFTS alerts so you’ll know when future articles become available, and enjoy this related read:

Laura Rascaroli, ‘Sonic modernities: capitalism, noise, and the city essay film’

- Let the Fire Burn, Zeitgeist Films, https://zeitgeistfilms.com/film/letthefireburn.

- This approach is sometimes called compilation documentary, as in the films of Esfir Shub and Emile de Antonio. More recently, the bloom of archival-only documentaries, like Senna and The Black Power Mixtape, have been called “archival verité.” Robert Greene, “Expiry and its discontents: Let the Fire Burn and How to Survive a Plague,” September 12, 2014, Sight and Sound, https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/comment/unfiction/expiry-its-discontents-let-fire-burn-how-survive.

- Todd Spangler, “Netflix Tops 57 Million Subscribers in Q4 as U.S. Growth Slows,” January 20, 2015, Variety, https://variety.com/2015/digital/news/netflix-tops-57-million-subscribers-in-q4-as-u-s-growth-slows-1201409712/.

- Let the Fire Burn, New on Netflix USA, https://usa.newonnetflix.info/info/70274329.