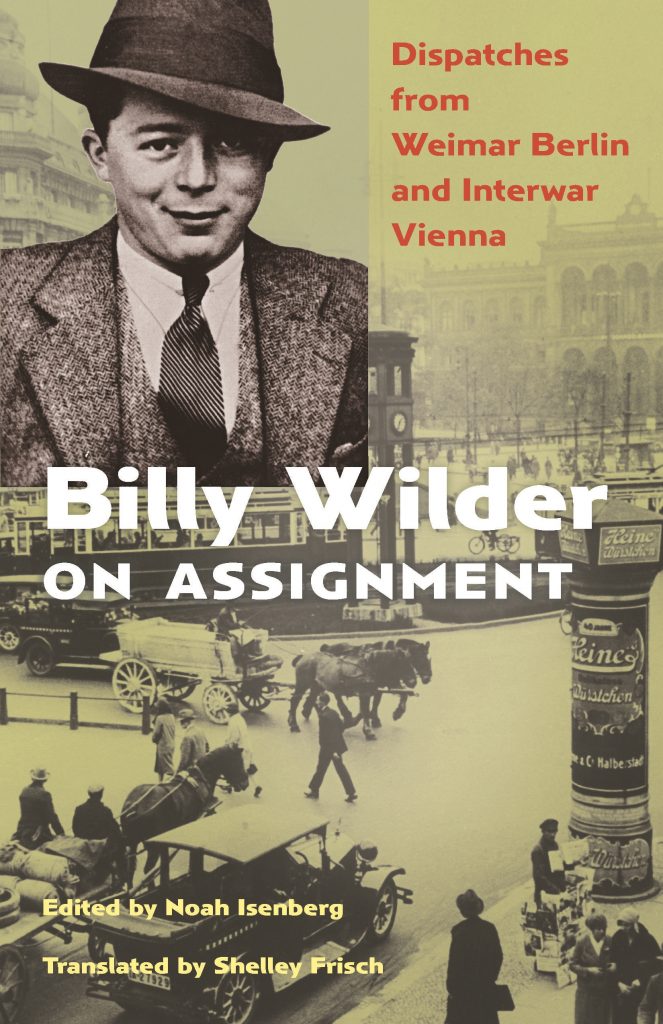

Available now from Princeton University Press

This conversation was edited and condensed.

Freda: I loved reading the book. I thought your introduction is fantastically informative about Billy Wilder, situating his life within the context of Weimar Berlin and 1920s culture too, really fascinating. I was struck by the language in these pieces.

Isenberg: There we really need to thank Shelley Frisch. She translates with such extraordinary aplomb, it’s amazing. Translating is so hard. I’ve done it and I’m not terribly skilled at it and Shelley is just a wizard. And we owe her a great deal in making these texts accessible to people who don’t otherwise have the German language skills to read them. That was the impetus for this collection: I’d worked with [these texts] over the years, I happen to have done my graduate training in German, so I had the access and I was grateful for it, but I was also equally upset and kind of miffed, perplexed, and even borderline depressed that my Anglo-American comrades couldn’t have access to these texts. These are jaunty pieces. There’s a certain liveliness to them, and that comes across in the German, and thanks to Shelley Frisch, it really comes across in her rendering of it in English. The snappiness of Wilder’s language – a snappiness that will ultimately make it into his American screenplays and be translated into the screen, is definitely on the page in these early articles of his.

Freda: Yes, I love your word “jaunty.” It leads to this broader issue of language and description and style. There’s that wonderful quote from [Charlotte] Chandler’s [biography] Nobody’s Perfect, of Wilder saying that “to know me, you have to know Vienna of 1906. This was a world of whipped cream and cream cakes.” That nostalgia for the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and Berlin of the 1920s. In that milieu, it was language all the time. It was café culture, when people actually read newspapers and spoke to each other. He was a writer, his creativity in terms of these little pieces – feuilletons, cultural essays. It’s such a lovely genre, kind of like Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag. Little daily flashes of imagery, not pre-directorial in any specific training, but a jaunty orientation to reality.

Isenberg: Yes, that combined with acute observation – the powers of keen observation of people in his midst. And likening it to Susan Sontag or Joan Didion or Roland Barthes is maybe not all that wide of the mark. Here is someone who is enormously perceptive but also enormously playful. Because he’s Wilder and is someone who likes to add a little mischief to whatever he’s doing, you do have a bit of poetic license.

During the time that he’s writing there is what’s known in Weimar Germany as Neue Sachlichkeit, The New Objectivity, with the best-known example being Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927), this great Soviet-inspired montage of Berlin. The whole point of the New Objectivity was to present the facts, whether on the screen or on the page. Obviously what Wilder’s doing isn’t exactly that, you have those acute or keen observations but you also have someone who’s having a good time, spinning a yarn, telling a good story. That is one criticism of the New Objectivity phase in visual arts and culture: there was a certain coldness to it. And you don’t have that in Wilder’s writings at all. Exactly the opposite: they radiate warmth and there is a personal voice that’s often there. In some cases it’s Wilder’s voice, and in some cases it’s an invented voice. There’s that piece (“Wanted: Perfect Optimist”) when he takes on the persona of being a hardboiled New York tabloid journalist writing on the person who’s hired to smile all day for that marmalade company. He’s just having a good time.

Freda [laughing]: That’s a wonderful piece.

Isenberg: It is. And it reminds me of the “Shouts & Murmurs” column in the New Yorker where sometimes you’ll see there’s a single line that’s ripped from a tabloid piece, and then an author will create a humorous story out of that. I don’t know whether young “Billie” caught a notice of this story somewhere and then made it into his own, but it does seem to have that sort of “Shouts and Murmurs” style to it.

Freda: He has an attitude, he’s not an intellectual, and maybe that’s where my analogy went wrong; he’s not even really an essayist. Although I love “The Art of Little Ruses,” which is about him complaining why aren’t people taught to dissemble and lie – because this is the most important thing you need to learn. This goes back to this issue of language and description. It starts out, “I don’t want to come right out and insist that, starting this very day, schools teach the art of lying, by which I mean using postures and facial expressions, gestures and inflections of the voice to convey the opposite of truth with sweeping powers of persuasion and achieve smashing success.”

Isenberg: You’re saying that he’s not an intellectual, which is so true, and he would never want to have any of the stuffiness of an intellectual. He’s a born entertainer so that’s his objective in these pieces… I love the piece that you mentioned, “The Art of Little Ruses” which I think is in some ways a nod to Oscar Wilde, or at least has a certain Wilderian (if you’ll pardon the pun) feel to it. “The Decay of Lying” by Wilde and “The Art of the of the Little Ruses by Wilder” – so we’ve got Wilde and Wilder.

There’s another one, “Anything but Objectivity,” which may in fact be viewed as a little bit of a barbed critique of intellectual culture at that time. He clearly knows these philosophers and sociologists and other thinkers and artists who were prominent at that point in time in Weimar Berlin and Vienna between the wars – [Sigmund] Freud and his colleague [Alfred] Adler and Richard Strauss and Arthur Schnitzler – he claimed to have interviewed all four of them in a single day. That was one of the more audacious claims by young Billie. I think he just figured that there’s no way that anybody could ever verify whether [he had]. There are no extant articles, no interviews. So I think that was Wilder being Wilder, or being Wilder than Wilder perhaps. I’ll stop.

Freda: Wasn’t it in a later interview when he said “Well, Freud kicked me out, but at least I got kicked out by Freud. That was the status symbol.”

Isenberg: There’s this profile of the French playwright Claude Anet, and Wilder’s adaptation of Anet’s Ariane, jeune fille russe (Ariane, a Russian Girl) is what forms the basis of Love in the Afternoon. I’m almost obsessed with the idea of Wilder as a young journalist in Vienna between the wars and in Weimar Berlin laying the foundation for a lot of the work that he would do as a screenwriter in Hollywood. You can’t see everything that he would later do in these early texts but there’s a lot that’s there.

I was doing an interview for a journalist at the Observer in the UK who wanted to know some of the examples, and I [mentioned] a sort of alienation in the big city, that struggling to get by and being a little bit of a schlemiel – an architect of one’s own misfortune. There’s a direct line between that and C.C. Baxter, Jack Lemmon’s character in The Apartment. I thought I was going out on a limb, and maybe I was, but then I saw a recent short documentary on Wilder, and the German filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff is interviewed in it and he makes exactly that same claim, so I felt vindicated by Schlöndorff.

Freda: It’s flawed, but in Trespassing Bergman [(2013)] you have all of these directors and it’s quite fascinating, even the most more obnoxious ones. It would be interesting to have a series of filmmakers speak about Wilder.

Isenberg: It’s a recent documentary it came out maybe two years ago and it’s called Never Be Boring, which I suspect is probably a line from Wilder. I can’t actually find proper attribution.

Freda: Not as easy as Nobody’s Perfect.

Isenberg: The epitaph on his tombstone is “I’m a writer, but [then] nobody’s perfect.” Schlöndorff interviewed Wilder at length and did this documentary [with Gisela Grischow] in the 1980s called [for its English release] Billy Wilder Speaks, and it’s the German biographer Hellmuth Karasek who was interviewing Wilder for the German language biography that came out a little bit after that so Schlöndorff tagged along so he’s on screen a lot in that earlier documentary. It’s in the later one that I just referenced, where he says [that with] CC Baxter you can really trace the line back to Wilder’s Weimar Berlin writings as a young freelance journalist. That’s from maybe 2018 or so. You can stream it free on Amazon Prime.

Freda: I will, because for anybody writing about or teaching Wilder this is fascinating stuff. As you so beautifully observe here and in the book, it’s that kind of observation, that kind of orientation – the jauntiness, the way of seeing, the color of his language and how that translates in his films, which are notoriously variegated in terms of topic and genre. He really has a range as a director that, I think, you see even in these pieces, in the range of who it is that he’s interviewing — Vanderbilt, and then the Prince of Wales…

Isenberg: …Asta Nielsen. He’s just as promiscuous as a journalist as he is as a screenwriter and director, I would say. There is this promiscuity that drives him, and I mean that in all senses of the term.

Freda: And in a positive way.

Isenberg: Definitely very sex-positive! That variegated, as you said, number of topics and genres that he would later take up as a writer-director, you see that here in the range of a relatively small collection. Back to the extraordinary award-winning translator Shelley Frisch, when we were doing this together – me and my capacity as editor and she in her capacity as translator – there were certain texts that we decided just didn’t really fit, or wouldn’t really speak to an Anglo-American reader or just didn’t work well in translation. Sometimes you face that…But in this representative selection, you can get that sense you seem to just have noted yourself of the breadth, the range of somebody who’s really interested in so many different things. And that jauntiness comes across as he’s just flitting about, as he was known to do his whole life, you know this inveterate pacer, just sort of taking in everything that he can.

The point that you made moments ago about trying to think of his writing as a feuilletonist, as someone who’s trafficking in the sort of cultural reportage, in the feuilleton, and the writings of Roland Barthes or Susan Sontag… There are definitely affinities and I think it’s certainly worth making those references when thinking about Wilder’s journalism. The key difference is the element of play. And that mordant wit that is palpable on every single page of the book. In terms of style, he’s very interested, I think, not only in the sartorial habits of the Prince of Wales and of fashioning himself as a sort of elegant, natty dresser, but also in the style of writing, the form, achieving an elegance on the page. I think that he’s aspiring to that elegance already at a 19 [year old] and then early 20-something.

Freda: When you speak about humor, that’s present throughout [the book], but where he really goes to town is the [piece published in Harper’s] and again where I see the beauty of the translation because of the word choices…

I wanted to ask you about your great observation about [the New Objectivity] and his mediation of that tendency at that time. Either he states it in the first person or he’s quoting somebody: “Ignore the Neue Sachlichkeit,, except for…”. You mentioned Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, which is really kind of brutish. It’s always interesting to compare that film’s realism, with a Vertov – much softer, playful.

Isenberg: I think that the real comparison – and it says a lot about Wilder – comparing Ruttman’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City from ’27 to the production that Billy Wilder was involved in in the summer of 1929 and that was released in February of ’30, People on Sunday, which is such a love letter to Weimar Berlin. And the author of that love letter is Billy Wilder.

You’re absolutely right about comparing Vertov and Ruttman, for sure, but in People on Sunday it’s even more extreme because the film really presaged, I think, Neo-realism and also Jean Vigo and Paul Fejos, those sort of sun-dappled landscapes. It’s a very different feel and a very different aesthetic than that sort of steel-like, harsh imagery that you have in Ruttman’s film. To a certain extent, you see some of it in Man with a Movie Camera, but I think that if it’s not a love letter, it is definitely a kind of passionate interpretation of the joys and the art of filmmaking. You don’t see that in Berlin: Symphony of a Great City.

Freda: We don’t want to draw Wilder into everything, but he is this personality. He’s not only, of course, Jewish and had the terrible tragedy of his family during the Holocaust, but that personality, where he comes from in Vienna, his orientation, this sort of joyful playful quintessential beauty of German culture at this time. I think that you’re right with the film People on Sunday, where you get these beautiful studies at this precipice in world history. Every time I see that film I can’t help thinking, right around the corner from this beauty is…

Isenberg: I don’t know whether you saw [2017-2020 TV series] Babylon Berlin, but there’s a couple of scenes from People on Sunday that are actually cut into an episode, and of course you’re anticipating even more the rise of Hitler. In People on Sunday, there are a couple of points where you can get at least a vague sense of the storm that is brewing. There’s the scene for instance of that older man in the Tiergarten who’s sitting there and saluting the statues of these Prussians, the days of glory, and you can sense a sort of worship of Germany’s militarist past. But otherwise you’re absolutely right, that’s what’s so kind of haunting about the movie is that it’s made and there is something so joyful – they’re really just trying to squeeze as much as they possibly can out of a single day in the life of Weimar Berlin and these four people out on a double date.

But there is an element [in People on Sunday] of that so-called [New Objectivity] and that comes on the beach. Eugen Schüfftan was the cameraman on the film, and Fred Zinnemann worked as his assistant. You have those kind of almost August Sander-like photos that are taken on the beach, and that has a certain nod to that dominant trend of New Objectivity. But otherwise the film is much of a departure from it. There really isn’t any of that coldness or that sort of hyper-detailed focus on capturing the facts and nothing but the fact, so to speak – the facts stripped of the emotional content effect. I don’t mean to make the New Objectivity into our straw man, but I do think it’s a pretty stark departure from that and People on Sunday.

Freda: And going back to his writings, he brings all of this again to his second entrance into American culture, the Hollywood exile experience – exiled in paradise, to quote the book. Like so many others his adaptation is extraordinary. There are some really interesting pieces for film historians; his [piece on] Asta Nielsen I really want to give to my class if I’m showing a German Expressionist film. Thinking of the [New Objectivity] again it’s the acute observation, and then we leave the coldness for warmth, which is like a Vigo versus a Ruttmann.

Isenberg: People on Sunday is much more Vigo than Ruttmann. Again I don’t mean to make these false dichotomies, but I think you can see it. You know Pabst’s film Joyless Street, that’s a good one to teach with the Asta Nielsen profile by Wilder.

Freda: It’s a good one to teach but it’s grim.

Isenberg: But a nice counterbalance if you want more warmth and less grim is then to teach Vicki Baum’s novel Grand Hotel, which appeared just a couple of years later, and would become the source novel for Edmund Goulding’s Academy Award-winning film with [Greta] Garbo and [Joan] Crawford and the Barrymore brothers.

Freda: Pandora’s Box, of course, as well. All of these great films that are surrounding Wilder at this time. It’s interesting that he’s not this avid filmgoer that you would expect. I know he did write movie reviews.

Isenberg: Capsule reviews.

Freda: I guess he couldn’t find the forum to write other pieces like the one [he wrote on Erich von] Stroheim. That’s a long piece and it’s very interesting and his perspective on Greed (1924) – that’s exactly what he’s not interested in, in terms of aesthetics and reality and megalomania.

Isenberg: No, that’s not Wilder!

Freda: I want to bring up [another] piece I just adore, “Why Don’t Matches Smell That Way Anymore?”, in terms of what you were discussing about Wilder being [so] keenly observant. “Well, it was like this: a match whooshed gently across the striking surface, and light blazed up. And silently, eerily, the blue spirits’ flame arose…Oh, blessed fragrance from the sun-kissed leather cushions of a carriage!” I’ve just got everything underlined. I was thinking of where one trains one’s camera, how one composes a narrative, and what is that filmic frame.

I want to refer to Wilder’s return to Berlin with A Foreign Affair (1948), a film I discovered a number of years ago and fell in love with, a great example of Wilder weirdly being able to [craft] what seems like a kind of schizoid narrative of bombing and destruction, and the way he works with Dietrich and the experience of Germans in Berlin, that’s also a romantic comedy.

Isenberg: Where he comes to terms with his own personal loss. Mother, stepfather, extended family. In US servicemen’s uniform he returned to Berlin in 1944 and together with Hanuš Burger who’s a Czech filmmaker they did a documentary called Die Todesmühlen (Death Mills, 1945), which you can stream on YouTube. It’s just unrelenting footage of these piles of dead bodies from the camps and Wilder makes that documentary with Burger and then somehow a mere three years later is able to have fun, so to speak, with A Foreign Affair.

You could see that kind of acerbic wit in a lot of Wilder production, but here he is returning to a Berlin in ruins and dealing with the incomplete denazification process that hadn’t even really fully begun. You’ll see flashes of that in One, Two, Three (1961) as well. In an interview late in life when someone was asking him about his past, Wilder says, you know there are optimists and pessimists; the optimists died in the gas chambers, the pessimists have swimming pools in their backyards in Beverly Hills. If you extrapolate from that anecdote –I’m not gonna put him on the couch, but I think there is a certain degree of survivor guilt and yet he’s coming to terms with it by way of comedy. And Marlene Dietrich, as she so often is, is marvelous in that film.

I need to make a plug for a dear friend and colleague of mine and I’ve been indebted to this work as well, and in my own writings on Wilder, and that’s a book that took the title of that film, it’s called A Foreign Affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films (Berghan, 2008), by Gerd Gemünden who teaches at Dartmouth College.

Freda: I have it! It’s really great.

Isenberg: It is really great and in fact I give him a little shout-out in the editor’s introduction.

Freda: I was just thinking about this realism and attentiveness to detail and then humor, and we’re getting to Wilder’s return to Berlin. I was also thinking of [Wolfgang] Schivelbusch’s In a Cold Crater, that fascinating book about Berlin at that time.

Isenberg: There’s another good book by a guy named Robert Schandley called Rubble Films that I think you may find interesting.

Freda: I read it too. I like to [teach] that and Schivelbusch with the trilogy Murderers Among Us (1946) and Germany Year Zero (1948) and A Foreign Affair – three radically different ways of negotiating that [history]. But Wilder’s is the most powerful in some ways.

Isenberg: I agree, and I’m a big fan of Murders Among Us, but I agree about A Foreign Affair. You’ll get no argument from me.

Freda: Thank you for editing this book. I’ve already of course told my mother to read it.

Isenberg: It’s those people I want to reach, that I care about. Your mom, my mom. Those people in film, if they can learn something from this, fabulous. But it’s those ever-elusive general readers – they’re the target audience for this book. And the reception has been like a warm bath. They have embraced this; it’s really lovely.

Freda: That’s beautiful; that’s how it should be. And it’s because of the way that it’s framed, the way that you’ve edited it, its readability, the chapter segmentation, the translation, the font…It was a real pleasure to read, and to discuss with you.

Isenberg: Thank you, the pleasure was mine. Great chatting. Nice kaffeeklasch and you take care.

Freda: All right, you too.