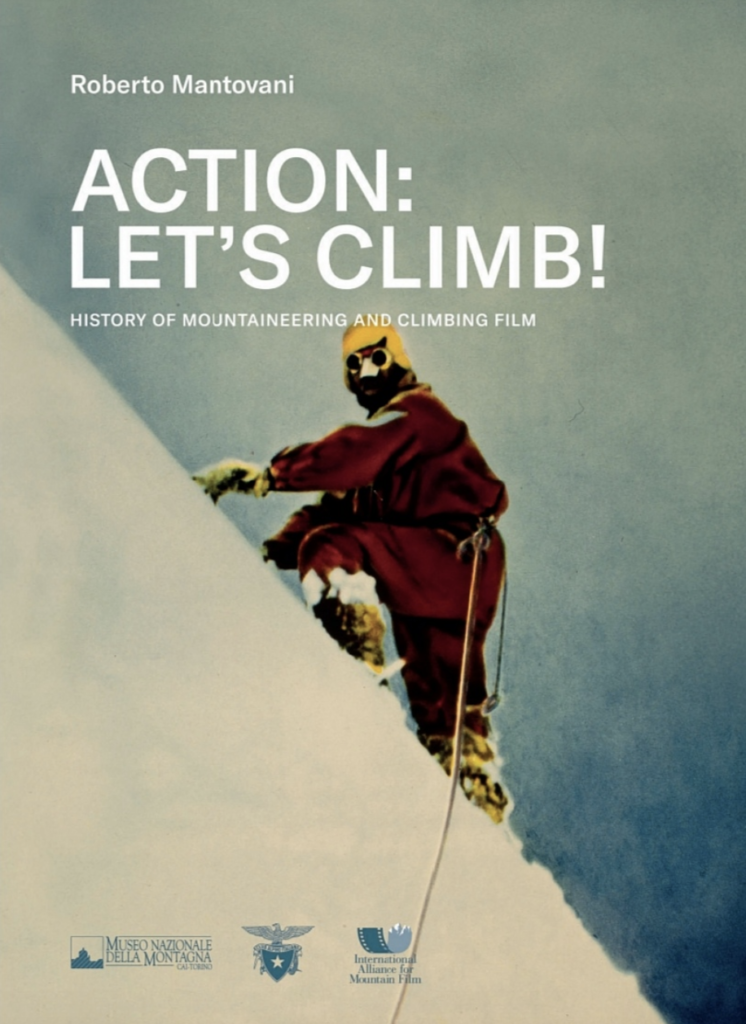

by Roberto Mantovani

C.A.I. – Club Alpino Italiano, 2020. 251 pages

$39.27, €39,90 (format), ISBN 9788879820912, English translation of Ciak, si scala!

Reviewed by Kamaal Haque

Roberto Mantovani, for many years editor of the one of the major Italian mountaineering magazines Rivista della Montagna, has written a book on mountains films unlike any other on the topic. At times polemical, at times simply encyclopedic, Mantovani’s wide-ranging work both challenges and reinforces much of what has previously been written on the topic, beginning with the definition of what exactly a mountain film is. While claiming to sidestep the generic question, Mantovani defines his subject as those films “in which climbing and mountaineering act as a background to the stories offered to the film-goer or – and we are talking about the majority – are the actual topic on which an ever more important number of titles is centred” (15). Thus, he is, as his subtitle suggests, mostly interested in “mountaineering and climbing film,” where the focus is on the act of ascent and descent.

This structure works, with one large exception, namely that of the Bergfilm, the classical German mountain film of the 1920s and 1930s most famously directed by and/or starring Arnold Fanck, Luis Trenker and Leni Riefenstahl. After chapters on the earliest mountain films – unsurprisingly the history of mountain film begins with a few years of the beginning of the history of film – Mantovani writes a chapter on “The Long Season of the Bergfilm.” Here, Mantovani deviates from defining the scope of his books as focusing on films involving mountaineering or rock climbing. He even admits so, writing “Many of the films listed on the pages above lie outside the specific focus of our story. Nevertheless, we believe it necessary to mention them” (58). Indeed, the Bergfilm actually disproves Mantovani’s opening statement on the first page of his introduction: “If you flick through the specialist film magazines and websites the words mountain and mountaineering never appear under the ‘genre’ heading” (13). Mountain films do appear as a genre in film studies, sometimes exclusively consisting of, but at a minimum containing, the classical German mountain films of the interwar years. Confronted with the most prominent subset of his subject, Mantovani expands his definition to include not only such obvious mountain films as Der Berg ruft (The Mountain Calls, 1938), but marginal productions such as Der Kaiser von Kalifornien (The Emperor of California, 1936) (both directed by Trenker) and films with no clear connection to the mountains such as Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938). Mantovani may wish to define the genre anew, but confronted with an existing corpus of films, he seems very much caught in the shadow of the Bergfilm.

Since the book is organized chronologically, further chapters discuss the developments in mountaineering and climbing cinema in the postwar years, one decade at a time. For Mantovani, there is a clear progression. Mountaineering film reaches its apogee in the 1970s and early 1980s. This is a time when not only has the camera reached mountains all over the world, but ice climbing’s development has added a new subgenre to the movies produced (118). Furthermore, the “Californian Dream” of Yosemite’s granite walls has become an ever more present topic as the American interest in climbing films increases. 1975 marks Clint Eastwood’s role as a spy who climbs in The Eiger Sanction, possibly the high point of large-scale Hollywood involvement with climbing in feature films.

But then the perfect becomes the enemy of the good. Mantovani bemoans that at the end of the 1980s, “perfectly photographed and filmed sequences ever more frequently came out on top in the battle with the director’s eye and the artistic quality of the production” (137). He blames television productions for this alleged decline in quality and he returns to this topic in each subsequent chapter. Of film in the 1990s, he writes, “in spite of a marked improvement in image quality, we can detect a definite deterioration in the artistic level of production” (146). The 2000s often provided “perfect images but not much cinema” (174) and “the 2010s saw a marked increase of products painstakingly researched down to the smallest details, backed up by amazing photography and undeniably spectacular shots […] but of scarce cinematographic calibre” (210). Of course, such a critique is subjective and difficult to prove, especially as many of the films Mantovani highlights in the chapters from 1990-2018 are productions which he elsewhere praises. But the takeaway is clear. In Mantovani’s view, the quality of cinema is inversely proportional to the quality of images in the film. This argument has many issues with it, not the least of which is that it seems to equate quality with simple resolution.

In addition to discussing mountaineering and climbing films, the chapters on postwar film generally include information on the burgeoning mountain film festival scene. Mantovani provides quite a bit of information here. In addition to discussing the festivals themselves, the book contains several useful tables on film awards. Surely, only the most devoted of mountain film festivalgoers know which film has won the most grand prizes at such festivals (Freedom Under Load (Slovakia, 2016)) (199). Without question, Action: Let’s Climb! is a worthy read for anyone interested in the history of mountains and cinema. The book’s wide range is truly impressive. Films from dozens of countries are covered. Mantovani’s work functions best as a source to find new films to watch. His critical judgments are much less secure than his encyclopedic knowledge of mountaineering and climbing cinema. Both experts on Fred Zinnemann and on mountain films will find it puzzling to learn that his Five Days One Summer from 1982 is “xonsidered one of the most successful mountain films” (127). Mantovani makes a similarly unusual argument for Werner Herzog’s Schrei aus Stein: “It goes without saying that Scream of Stone, if for no other reason than the director’s renown, will be considered an icon of mountain and mountaineering films in the future, too” (147). Critical and popular reception strongly suggest the opposite. These judgments coupled, with several typographic errors (“Fank” instead of “Fanck,” for instance (40)), as well as some bizarre claims (contrary to Mantovani, Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi are not “both excellent climbers” (217))1, detract from an otherwise admirable book. For the reader willing to look past the occasional misstep, Action: Let’s Climb! provides an enormous amount of information on mountaineering and climbing cinema throughout the world.

Footnotes

1While Chai Vasarhelyi is an accomplished skier, she is not a climber, unlike her professional climber husband Chin. Cf. Chase, Lisa. “Free Solo’s [sic] Director Doesn’t Give a F**k about Climbing.” Outside. Sept. 12, 2018. https://www.outsideonline.com/culture/books-media/elizabeth-chai-vasarhelyi-free-solo-movie/ Accessed Oct. 3, 2022.