By Gregory Brophy

Creative Statement

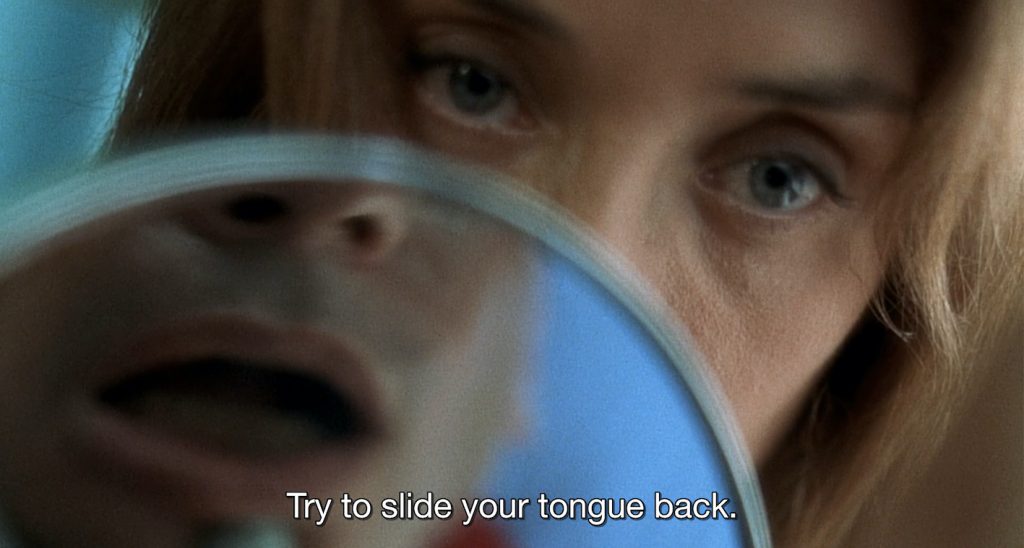

My essay in the current issue of New Review of Film and Television explores the fraught intersection of disability and gender in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, a film that adapts the memoirs of Jean-Dominique Bauby to evoke a visceral experience of ‘locked-in syndrome.’ Committing to extensive literal first-person perspective, the film deploys the camera as body double to explore the intimacy and terror of being touched (intrusions to which both patient and viewer must yield). The film’s haptic vision, paradoxically enabled by Bauby’s disability, mounts a challenge to popular cinema’s dominant gaze and the normative body it so often assumes on behalf of viewers.

When the editors of the New Review invited this issue’s authors to contribute tie-in pieces, I considered how a video supplement might grant readers more direct sensory access to the phenomenological analysis of film conducted in my written essay. Videographic work is new to me, but it’s been one of the most invigorating aspects of the past year’s shift to online learning, and I’m eager to explore how that experiment may reshape post-pandemic teaching and research.

Tracing across film history and genre, “Untouchable” gathers together exceptional moments of camera contact, probing the haptophobia, or fear of touch, that such collisions typically trigger. While cinematic norms tend to naturalize the pose of a distanced observer, unsusceptible to touch, the Diving Bell’s camera is manually examined by characters, caressed, addressed, and even dressed by others. How strange to watch an actor place a hat atop a camera! It seems almost an affront to the machine’s dignity. But such peculiar gestures reveal much about the unspoken premises of cinematic perspective, the strangely disembodied view we expect to occupy, a touch-deprived existence that Bauby’s disability exposes as itself pathological.