By Raed Rafei

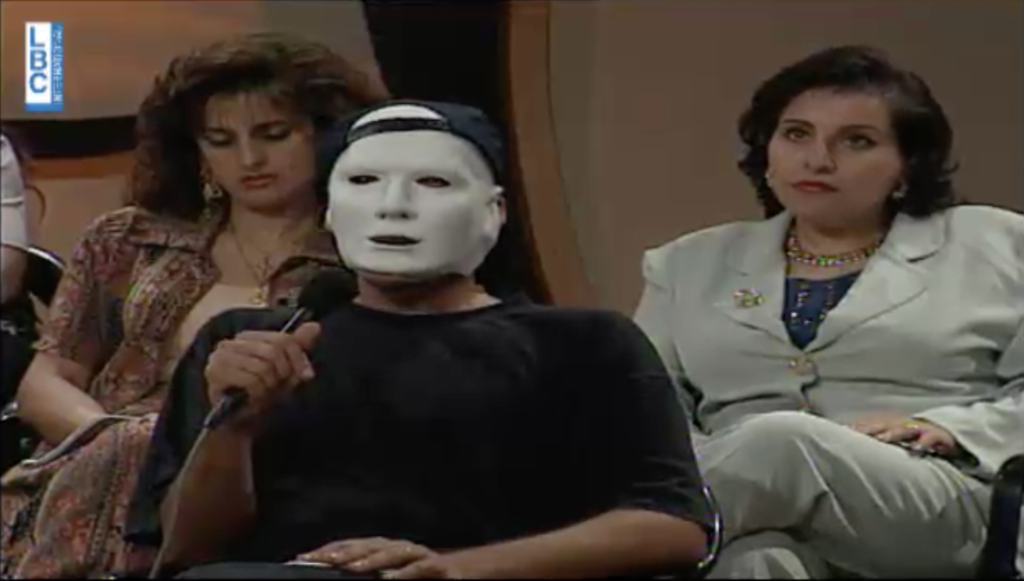

Two men with their faces covered by masks sit in a TV studio surrounded by psychiatrists, scientists, legal experts, religious figures, and a small group of “regular” people. I remember this episode of a popular Lebanese TV show from April 1996 as my first encounter, and that of the Lebanese public more generally, with a major national televised debate on the topic of homosexuality. Watching it again twenty-eight years later with an odd mix of amusement and dismay invites some contradictory thoughts about the question of queer visibility and audio-visual representation, the subject of my article, “Queer (In)Visibility and the Production of Queer Space in Postwar Lebanese Film”, scheduled for publication in issue 23.3 of New Review of Film and Television Studies.

The episode of al-Shāṭir Yiḥkī (Let the Brave Speak Out), titled “al-Jins Ajnās” (“The Many Types of Sex”), tackled a taboo issue for the Lebanese met generally with loathing by society, evident in the unsettling negative opinions of people on the street surveyed in the vox pop section of the show. But despite attempts to cast a positive light on homosexuality, I cringed at the way it was pathologized by some of the mental health experts, who tried to explain same-sex desire with a Freudian analysis resting on “unwholesome” childhoods spent with overbearing mothers and absent fathers. I saw a total absence of lesbian women, a clash between antiquated religious values and western-influenced scientific and legal views, and an emphasis on private freedoms and the respect of independent selfhoods in a nation struggling with identitarian questions after a fifteen-year-long sectarian civil war. But what stood out to me most was the defiance of the two masked queer guests who repeatedly insisted that they felt perfectly normal and in harmony with themselves. One of them, presented as nūn or the letter n in Arabic, poignantly noted that their mask, used to protect their identity in a country that criminalizes same-sex relations, was “the mask of people’s ignorance.”

The techniques used to hide (in plain sight) queer subjects in the show merit further consideration. In pre-recorded reports punctuating the stage discussion, one of the faces of the queer interviewees was pixilated, another was backlit and filmed behind a white veil, and a third was represented by their shadow on a wall. In the TV studio, two wore white masks and their voices were distorted with a pitch shifter effect that made them much deeper than “normal.” Ironically, they sounded more masculine in a caricatural way that contrasts with common Lebanese misconceptions of queer men as necessarily “feminine.” The producers of the show probably wanted to demonstrate that queer individuals exist and are just regular human beings. However, the use of these techniques to singularize and isolate them, as well as the repeated dispute among the experts in the show over the percentage of homosexuals in society (placed roughly between 4 and 15 percent), helped to consolidate the categorization of homosexuals as a minority and a deviation from a norm, albeit a common one for some in the discussion. While the minoritizing view, as Eve Sedgwick calls it, has political importance especially in a country where abuses and violences against queer bodies continue to exist, it’s essential also to consider queerness through other, more capacious perspectives.1 As I listened to the “regular” participants, the ones with uncovered faces, presumed to be heterosexual external bystanders to the question of homosexuality, I wondered how many felt various forms of same-sex desire, difficult to be classified neatly.

In a critique of how the LGBTQ community is produced as a homogenous minority in Western discourse and discussed only in terms of freedom of expression and sexual practice, Ghassan Moussawi instead unpacks queerness in Lebanon by highlighting queer tactics and strategies for everyday life as ways of understanding local and regional politics.2 Moussawi criticizes the imperative of coming out, stressing that Lebanese queer people strategically use “indirect ways to signal their non-normativity.”3 For Moussawi, the interplay between “concealment and disclosure” that happens in both private and public circles plays “a central role in reproducing and resisting normative understandings of queer visibility.”4 As Sedgwick reminds us, coming out is not a straight movement from tradition to modernity but rather a tactical performance that might involve both boastful moments and retractive silences depending on context.5 With this conceptual framework in mind, my NRFTS article analyzes the Lebanese documentary Shū Bḥibak (How I Love You) (Akram Zaatari, 2001), a pioneering essay film that represents the desires and relationships of queer people without narratives of homophobia and oppression, often thought to be characteristic of the Middle East. Unlike the talk show, Zaatari uses overexposure and closeups on body parts to create a sensual and erotic representation of his characters. I see in the film a form of resistance to the focus of “colonial modernity and its afterlives” on visuality and seeing as regimes of knowledge and power.6 I suggest that by blocking an Orientalist gaze that unveils and exposes, How I Love You offers instead forms of haptic seeing that activate other senses, mainly touch.

When I first saw the TV show, I was a first-year biology student at the American University of Beirut and not yet “out” in a Western sense (not even, maybe, to myself). I remember being in a dorm room with a couple of friends sitting in front of a small TV. I don’t recall what I felt exactly at the time. But with the scarcity of any positive information around homosexuality or access to queer stories and experiences, I think I was invigorated by the discussion and the defiant voices of the queer participants. Today, there are several openly queer public figures in Lebanon who challenge identitarian discourses and ponder the forms of visibility to which Lebanese queer people might aspire. Last summer, an attack against a drag show in Beirut was carried out by a Christian vigilante group self-appointed as “Soldiers of God” in an atmosphere of heightened homophobia from the corrupt political class.7 This raised questions about safe and responsible actions in an environment where visibility for certain queer individuals can be deadly. Sadly, the recent atrocious murder of a Syrian transgender woman in a Beirut suburb was a stark reminder of the many vulnerabilities within the queer community of sex workers, immigrants, and other marginalized individuals.8

Jasbir Puar and Maya Mikdashi argue that sexuality is always tightly imbricated in bio-political forms of control, stressing that the study of queerness in the region has to take into account the war-torn realities of the Middle East and the responsibility of US regional politics and military interventionism for the current state of affairs of the region.9 They write, “The precarity of queer life is not exceptional in these [the Middle East’s] sociopolitical spaces: it is additional precisely because war, genocide, occupation, oppression, dictatorship, terrorism, and killings are part of the everyday fabric of life for many people who live in the region.”10

This statement is particularly resonant today with the ongoing devastating war on Gaza (and to a lesser extent, southern Lebanon) by the Israeli government, which also claims to be the only democracy in the region championing LGBTQ rights. This pinkwashing tactic attempts to render invisible the many forms of queer lives and resistance in Palestine and the region, as a number of Middle Eastern queer activists have noted. A widely circulated statement published in November 2023, titled “A Liberatory Demand from Queers in Palestine,” insisted on the impossibility of social and political emancipation and life and dignity for queer individuals amid a deadly military occupation. Importantly, the statement called out the blind spots of those in the international queer community who do not recognize “the racialized, capitalist, fascist, and imperial structures that dominate us.”11 Similarly, recent calls to boycott official pride festivities in some Western cities, routinely accused of being coopted by self-serving corporations and political groups, insisted upon a queer visibility that is not complicit with genocide and upholds justice not only for Palestinians but for all oppressed peoples.12 Many of my queer Arab friends living in so-called gay-friendly Western cities like Berlin say they feel that being visibly queer is welcome and even celebrated but coming out in solidarity with Palestine, by wearing a Keffiyeh for instance, is sometimes frowned upon and can even be dangerous.

The imbrication between queer public visibility and political struggles in Lebanon has a long history. Mazen Khaled, another filmmaker I focus on in my article, was among the first group of people to raise a rainbow flag on the streets of Beirut in 2003. It was not during a pride march. It was at a protest against the US invasion of Iraq, marking the central role of queer groups in the country’s anti-war movements.13

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008), 1. ↩︎

- Ghassan Moussawi, Disruptive Situations: Fractal Orientalism and Queer Strategies in Beirut (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2020). ↩︎

- Moussawi, Disruptive Situations, 88. ↩︎

- Moussawi, Disruptive Situations, 92. ↩︎

- Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet, 68. ↩︎

- Gayatri Gopinath, Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 7. ↩︎

- Rasha Younes, “Violent Assault on Drag Event in Lebanon,” Human Rights Watch, August 25, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/08/25/violent-assault-drag-event-lebanon. ↩︎

- See the statement released on May 17, 2024, by the LGBTQ rights organization Helem in Lebanon on its Instagram page, https://www.instagram.com/p/C7EweOGIqGT/?hl=en&img_index=6. ↩︎

- Maya Mikdashi and Jasbir K. Puar, “Queer Theory and Permanent War.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 22, no. 2 (2016): 217, https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3428747. ↩︎

- Mikdashi and Puar, “Queer Theory,” 219. ↩︎

- QueersinPalestine, “A Liberatory Demand from Queers in Palestine,” Instagram, November 7, 2023, https://www.instagram.com/p/CzWvUTULg27/?hl=en&img_index=1. ↩︎

- Yaffasutopia, “THERE IS NO PRIDE IN GENOCIDE!” Instagram, June 3, 2024, https://www.instagram.com/p/C7w1LuIAy3q/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==. ↩︎

- In a post on his Facebook page, Khaled shows the image of a short article in the popular Lebanese newspaper As-Safir by journalist Sahar Mandour, where she writes positively about a group of queer people raising a rainbow flag at a large 2003 protest in Beirut against the US invasion of Iraq. See: Mazen Khaled, “Rainbow Flag,” Facebook, September 26, 2017. ↩︎

Bibliography

Gopinath, Gayatri. Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

Helem. “A statement issued by Helem regarding the murder of the trans woman Tala.” Instagram, May 17, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C7EweOGIqGT/?hl=en&img_index=6.

Khaled, Mazen. “Rainbow Flag.” Facebook, September 26, 2017.

Mikdashi, Maya, and Jasbir K. Puar. “Queer Theory and Permanent War.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 22, no. 2 (2016): 215–22. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3428747.

Moussawi, Ghassan. Disruptive Situations: Fractal Orientalism and Queer Strategies in Beirut. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2020.

QueersinPalestine. “A Liberatory Demand from Queers in Palestine.” Instagram, November 7, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CzWvUTULg27/?hl=en&img_index=1.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008.

Yaffasutopia. “THERE IS NO PRIDE IN GENOCIDE!” Instagram, June 3, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C7w1LuIAy3q/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==.

Younes, Rasha. “Violent Assault on Drag Event in Lebanon.” Human Rights Watch, August 25, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/08/25/violent-assault-drag-event-lebanon.