by Tim Shao-Hung Teng1

There is no denying that the current movements for social justice in the US have much to do with cinema and the broader realm of visual culture, where questions of representation, visibility, and power remain crucial and contested. The #MeToo movement, when it first took off as a high-profile phenomenon on social media, centered around sexual-abuse allegations against a Hollywood industry mogul, whereas people awaken to the call of Black Lives Matter through the viral videos documenting—sometimes live broadcasting—the horrendous murders of Black Americans by police. To film and media educators, images and the industries that produce them thus constitute valuable sites where instances of social inequity can be exposed and critical awareness nurtured.

Things get complicated, however, when such pedagogical tasks take place in a cross-cultural setting. How, for example, does a regional cinema far away from the American mainland relate to the social dynamics unfolding in the country today? In times of crisis, how should educators fulfill the requirement of knowledge production, which concerns cultures and histories of a particular region, while advancing the cause of social justice, whose resonances have a much wider reach? These were the questions that surfaced in the classroom of East Asian Cinema, a General Education course offered in the Spring semester of 2022 at Harvard University. With the course instructor and five fellow graduate students, I participated as a teaching fellow, attending lectures, giving guest lectures, and leading sections with a body of 130 undergraduates comprising mostly non-humanities majors.

Surveying major works from countries and regions including China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, our course is situated at the intersection of film studies and area studies. Its goal is to hone students’ visual analytic skill, on the one hand, and to acquaint them with modern East Asian history, on the other. Yet our self-positioning as East Asian film experts was complicated by the fact that we were teaching at an elite university in early 2020s America. We noticed that in these trying times, regional cinema can no longer stay complacent as an autonomous study of subject matters “out there.” Rather, it is compelled to respond, and, if need be, adjust to social agendas seeking to build more just communities, agendas that shape the here and now of our pedagogical mission. This short essay documents some productive moments in which present political climate urged us to reflect on the way we taught. While it offers a general narrative on the course, the opinions detailed below are all mine; they by no means speak on behalf of the teaching team or the students.

*

Born around the turn of the twenty-first century, the present generation of college students spent their formative years attuned to discourses of social injustice rippling across media in the wake of major national events such as the Trump elections, the Harvey Weinstein scandal, and the murder of George Floyd and many other Black lives. On the level of the university, Harvard has recently been called out on its nonaction toward several controversies involving its faculty members, including the sexual misconducts of three senior Anthropology professors2 as well as the false claim made by a Law School professor that comfort women forced into sexual slavery during World War II were voluntarily contracted sex workers.3 As these events and scandals percolated in the immediate and distant background, our students proved to be morally sensitized, with many bringing in invaluable insights that urged us to reexamine the syllabus, the canons, and research methods, thus breathing new lives into them.

Indeed, one thing I realized early in the semester was how much the classics had changed: viewed in the age of #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and Stop Asian Hate, certain classics appeared problematic in ways previous viewers would not have readily registered. An all-time favorite such as Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express (1994) became jarringly inappropriate due to its racist depiction of South Asian migrants in Hong Kong, shown in the first vignette of the film. As some students noted, these characters are portrayed using dark lighting, appear in blurred images given mere seconds of screen time, and are paired with traditional Indian music that intends to essentialize and exoticize their ethnicity.4 Featuring a man relentlessly pursuing a woman at a bar, this part of the film also sees Kaneshiro Takeshi’s Cop 223 pester Brigitte Lin’s drug smuggler with lines like “When a woman falls out of love, what she needs is a man’s shoulder.” While some students interpreted this scene as a parody of the pickup culture embodied by Kaneshiro’s attractive yet toxic character, others were less willing to let it off the hook, insisting on a critique of heteronormativity the film does indeed impose.

If Chungking Express represented a mildly disturbing case in point, a more controversial film such as Kurosawa Akira’s Rashomon (1950) demanded more careful deliberation. For previous iterations of the course, the film furnished an occasion for lively discussions of issues ranging from historical representation, genre and style, gender politics to literary adaptation. What made it problematic—and, to a particular few, triggering—this time around was the rape of the samurai’s wife in all four retellings of the story. Though only alluded to, the rape lies at the core of the film around which questions of power and agency revolve. In the face of present volatile gender politics, even a genuine question such as “Which character’s version of the story is more plausible?”—a good exercise in thinking about narrative reliability—can be fraught, because it suggests that the testimony of a sexual assault survivor can be faked and thus is not to be believed.

The case of Rashomon pointed to further complications, the more immediate of which concerned the need for trigger warnings, which are gradually integrated into film course syllabi nowadays. While students’ personal histories led us to believe that content warning given sufficiently beforehand could help block out unwanted traumatic experience, the teaching team debated whether administering these warnings would be the best solution. So-called content warning, after all, implies an uncritical equivalence of content and trauma, whereas the latter’s highly elusive nature suggests unrepresentability and untranslatability. Thought to be a precautionary measure of trauma blocking, trigger warning further raises the question of “comfort,” of the university becoming a place where comfort, rather than rigor, is prioritized. As Lynne Joyrich contends in her reflection on the issue, “there is something inherently discomforting in knowledge production, in the emergence of new thoughts that unsettle taken-for-granted assumptions—in, precisely, ‘critical thinking.’”6 In placing comfort above criticality, one might thus lose sight of a core function of humanities education. The issue is worth some consideration, too, from the perspective of regional cinema. For it is often those “unfamiliar,” “exotic” texts from the geographical elsewhere that are more likely to become targets of trigger warning demands. Classic East Asian films in this regard are more susceptible to labels of being triggering, politically suspect, “undemocratic,” or “uncivilized.”

Students’ political reading of the films also helped foreground problems resulting from the cross-cultural encounter between the West and the Rest. It was not uncommon that in their incisive criticisms, ethically conscious students interiorized contemporary views against sexism and racism to a degree that they retroactively applied these views to the texts of previous eras. Yet to what extent should Rashomon, a “foreign” text produced more than half a century ago and based on two early-twentieth-century short stories set in medieval Japan, be subjected to our progressive stance informed largely by contemporary liberal thinking? In a personal conversation with a faculty member who did not take part in the course, we pondered the possibility that such readings might risk reproducing a neocolonial structure, imposing too forcefully certain expectations not (yet) existent in non-Western, non-contemporary contexts.

The political response to social inequity also changed the way we applied close reading skills to films. In the past, a key exercise of teaching Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A City of Sadness (1989) was to unpack the meaning of inserting a deaf-mute photographer (played by Tony Leung) in the film. Students were guided to contemplate the oppressive nature of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist regime to which the oppressed Taiwanese could only bear silent witness. Yet this allegorical reading appeared problematic today. One student pointedly questioned the need for a reason for the film to feature a disabled character. To the student, it was just as plausible that the character simply happened to be deaf-mute. Polemics such as this seemingly returned us to the old debate of whether Third World texts should be read as national allegories. But more fundamentally, they challenged the method of symptomatic reading exercised at the expense of marginal others, putting on trial the very premise of film criticism, which has been so adept at distilling meaning from objectified women, sexual minorities, colonized peoples, and disabled characters.7

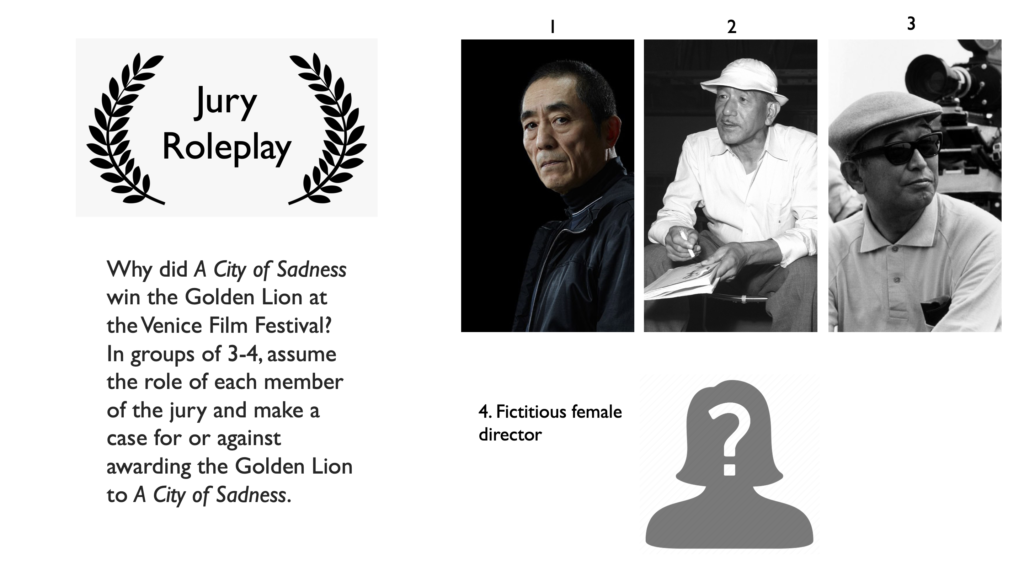

Despite the unresolved tension resulting from the encounter of US domestic politics and regional cinema, the benefits of tuning in to voices on social justice outweigh inattention. For one thing, students’ alertness to gender inequity makes teaching Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay on the male gaze historically meaningful again. The attentiveness to the objectification of women also sparked discussions in unexpected ways. In a group activity, I asked students to play the jury and debate whether they would give A City of Sadness the Golden Lion Award, which the film garnered at the 1989 Venice Film Festival. The jury members I came up with included Zhang Yimou, Kurosawa Akira, Ozu Yasujirō (the three auteurs covered in class thus far), and—to diversify this all-male list—a fictitious female director. My goal was to push students to focus more on the roles played by women in the film, and to think why this female director had to be fictitious. In their response, more than one student challenged the rationale of this design, asking: Is the female director there simply for the sake of representation? Is she allowed to weigh in on topics of “universal” aesthetics like the male auteurs do, or is she merely a token, a heuristic instrument, confined to comments about women and their representations onscreen?

*

Of course, the larger context within which the above scenarios take place is the corporatized neoliberal university. Increasingly, students take on the role of consumers to whose taste knowledge providers must make sure to cater. Yet with social justice as a synergistic force, customization in the form of preference polls, midterm evaluations, and content warnings need not be dismissed outright as selling out to the neoliberal regime. For customization also leads to conversations where students and teachers collectively explore what a syllabus can look like. Throughout the semester, we received a few inquiries demanding a syllabus that would be more capacious toward female directors and LGBTQ representation. In response, the instructor added Asato Mari’s Fatal Frame (2014) to the J-horror week while crowdsourcing advice on LGBTQ films for future iterations of the course. To be sure, adjustments like these necessitated longer conversations: a film about the budding though quickly repressed lesbian love in an all-girls boarding school, Fatal Frame was voted least favorite film at the end of the semester. Some students reasonably questioned the film’s conservative depiction of lesbianism as merely a transient teenage phase, while others expressed confusion with its plot.

From an educator’s perspective, it is of great importance to nourish students’ political conscience and accompanying spirit of critique; the question is how to channel that critical rigor into a productive energy suitable for cross-cultural discussions. My own view is to see social justice movements such as #MeToo not as a conclusion but as a starting point that introduces a new set of problematics. More specifically, there is a need to match students’ eagerness to critique with an eagerness to translate. #MeToo in this regard should first be provincialized, returned to the time and space of its happening; in this process, one can begin to ask how this version compares and translates to a different one, and how it is supported or hampered by differently established legal, social, and political institutions.

In the context of East Asian cinema, it might be useful to reference the recent accusations of serial sexual misconduct against renowned male directors in Japan’s film industry, which some Western media describe as being “on the verge of a delayed #MeToo movement.” The exposé not long after of director Kawase Naomi’s abusive behavior toward her colleagues further reminds us that #MeToo does not always operate along the male/predator-female/victim dichotomy.9 These cases call for a closer look into the work culture of Japan’s film industry, where filmmakers, regardless of gender, might all be structural extensions of an oppressive system. How are these cases received by the public? How does the industry respond to them? Does the legal system work in favor of the victims or those in power? Following these threads will likely reveal a different story than that of the Hollywood.

Provincialization also means seeing differences and making translational efforts on the local level of the text. Using Rashomon as an example, we might ask: Does the framework of female solidarity prevalent in Euro-American countries apply there, too? If vocalization of victimhood is not available to the assaulted character, what other subject positions will she have to develop? It seems her agency in this context is “tainted” by necessary compromises with the patriarchal norm, demanding the violated to be more strategic, manipulative, inconsistent, and hence aesthetically more innovative. How then does this subject position translate to questions of film form? This string of questions can go on. Its attempt at constructing a different model with which to understand a female subjectivity outside the liberal framework serves as a reminder that social justice movements cannot simply be abstracted and idealized to a universal status that in turn structures our viewing. Regional cinema in this way poses urgent questions about politics and pedagogy from the margins that require the center to cross over to address.

Footnotes

1This title is a riff on Rey Chow’s “The Politics and Pedagogy of Asian Literatures in American Universities,” in Writing Diaspora: Tactics of Intervention in Contemporary Cultural Studies (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 120-43. I would like to thank the course instructor Jie Li as well as fellow teaching members Shaowen Zhang and Patrick Chimenti for their generous input, which pushed me to think harder about my arguments.

2See the exposé first published in The Harvard Crimson in May 2020, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2020/5/29/harvard-anthropology-gender-issues/. Student and faculty protests are ongoing, as the university plans to bring back one of the implicated professors to teach a course in Fall 2022.

3See the editorial piece penned by Harvard Crimson’s editorial board: https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2021/3/8/ramseyer-comfort-women-paper/.

4The film’s racist depiction of South Asian migrants inspired one student to write a brilliant paper on the topic, where he drew on anthropological studies to show that most crime cases taking place in the titular Chungking Mansions have been associated with local rather than migrant citizens. See also Gordon Mathews, Ghetto at the Center of the World: Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2011).

5See, for example, Lynne Joyrich, “Keyword 8: Trigger Warnings,” differences 30, no. 1 (2019): 189-96; P. J. Jones, et al., “Helping or Harming? The Effect of Trigger Warnings on Individuals With Trauma Histories,” Clinical Psychological Science 8, no. 5 (2020): 905-17; Jeannie Suk Gersen, “What if Trigger Warnings Don’t Work?” New York Times, Sep 28, 2021.

6Joyrich, “Keyword 8: Trigger Warnings,” 191.

7See Hentyle Yapp’s insightful reading of Wen-ching’s disability in terms of speech and mediation, “To Free Speech from Free Speech: Marxism, Mediation, and Disability Aesthetics in Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s A City of Sadness,” Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies 15, no. 2 (2021): 169-85. Course instructor Jie Li incorporated the essay’s essential arguments into her lecture on the film.

8Quoted from https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/sion-sono-accused-of-multiple-sexual-assaults-1235125282/. These accusations were made against filmmakers Sakaki Hideo and Sono Sion as well as actor Kinoshita Houka.

9The original report published in Shukan Bunshuncan can be found on the magazine’s website at https://bunshun.jp/articles/-/53961. For English-language coverage, see https://www.indiewire.com/2022/06/naomi-kawase-accused-violence-on-set-1234731431/.

Read Tim Shao-Hung Teng’s article “Time, Disaster, New Media: Your Name as a Mind-Game Film”

Further reading:

Thomas Elsaesser’s article “Contingency, causality, complexity: distributed agency in the mind-game film

Marisa C de Baca’s review of The mind-game film: distributed agency, time travel, and productive pathology by Thomas Elsaesser

Madeleine Collier, “Unknown, Unknown, Delaware, Unknown”: The Mind-Games of Severance

We welcome proposals for this section of our site devoted to creative pedagogies. Should you be interested in contributing a feature spotlighting an innovative approach to teaching screen media, please submit a short description and brief bio to nrftsjournal(AT)gmail(DOT)com.