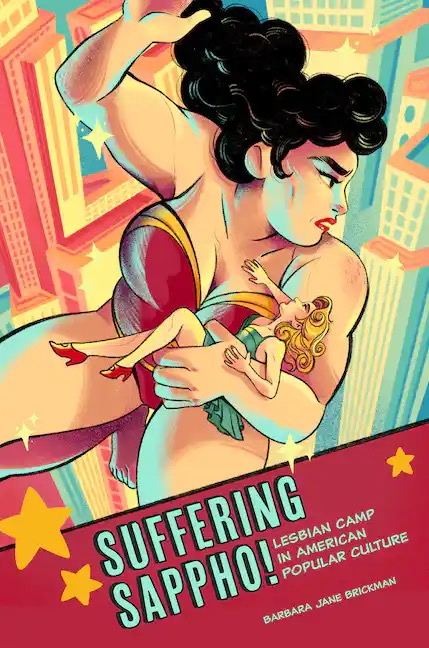

Barbara Jane Brickman’s Suffering Sappho! Lesbian Camp in American Popular Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2023) promises to uncover the least popular form of camp – lesbian camp – in the most unlikely moment of US American history, the Post-WW II era “often considered to be the most repressive and conservative era of the twentieth century” (Brickman 1). And yet, as Brickman argues, “lesbian camp … flourished on the pages, stages, and screens of American popular culture” (1), even as – or rather precisely because – the era was also uniquely obsessed with presenting queerness as deviant. For the lesbian, this played out in “five dominant types – the sicko, the monster, the spinster, the Amazon, and the rebel” (3) – each type differently fit for a camp reading in which pleasure and pain are complexly entangled.

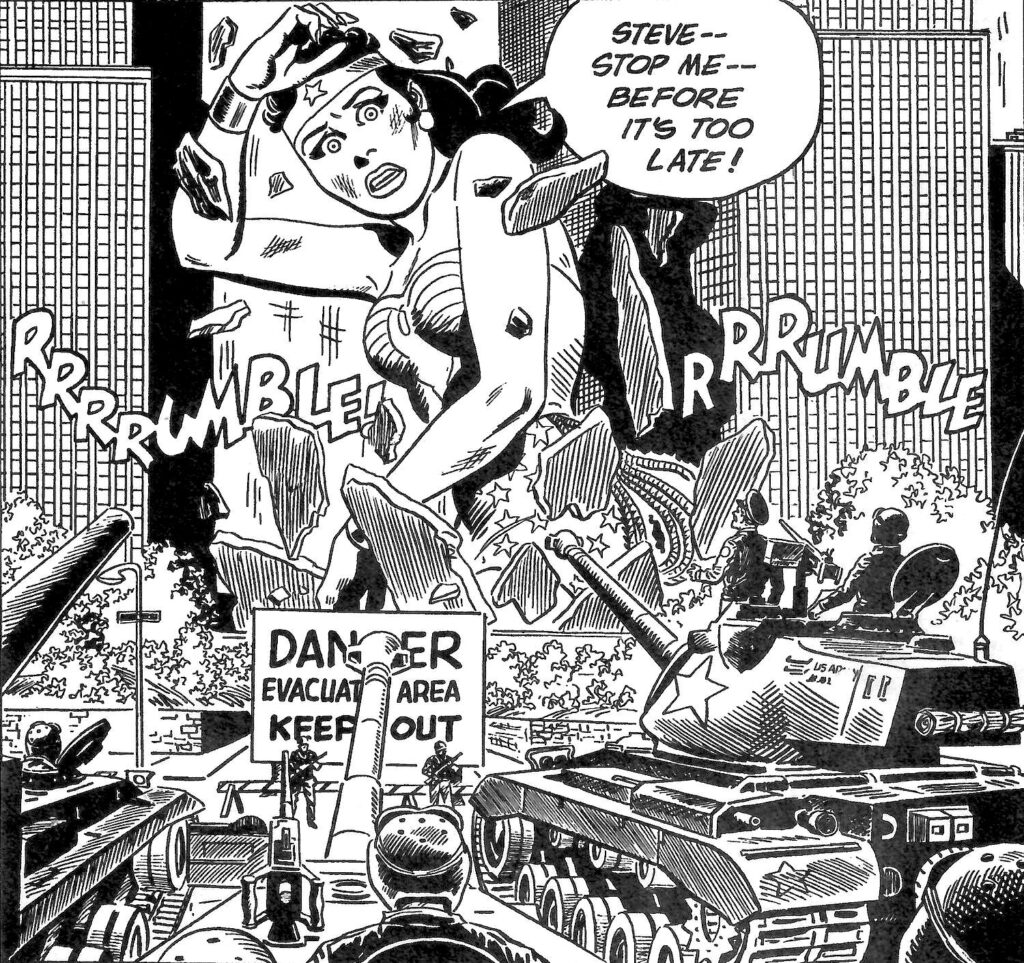

Suffering Sappho is, without a question, a book that you should judge by its cover. It is as pretty, witty, and gay as the cover itself, it delivers on the “larger-than-life lesbian menace” (3) that’s illustrated there, and offers smart, thought-provoking, and beautifully written analyses of otherwise often neglected texts. With elegant transitions and myriad connections between the chapters – whether it is Tallulah Bankhead showing up again in the final chapter on Black performers or pulp fiction making an appearance in the analysis of Wonder Woman – the book’s content and structure equally emphasize that lesbian camp was not a one-off thing in post-war America, but rather presented a pervasive part of the media landscape – from radio variety shows, to pulp novels, B movies, spinster sitcoms, super-hero comics, and club stages.

In my conversation with the author, Brickman reveals what role Jodie Foster played in her book’s “origin story,” which texts did not make it into her manuscript, why butch sensibilities are rife for reappraisal, and how understanding lesbian history is crucial to contemporary queer survival.

(The following Q&A was conducted via Zoom and has been edited for publication.)

Katrin Horn (KH): It is nearly impossible to begin this conversation in any other way, so I will just go ahead and embrace the stereotype. How do you define camp? To make the question more precise: you distinguish between “a model for lesbian camp, as well as camp reading practices” (Brickman 123; in connection to the Wonder Woman comic). In several other cases you differentiate between camp as an aesthetic strategy and “the camp” as a person. You describe, for example, Bertha Harris – author of “Notes Toward Defining the Nature of Lesbian Literature” – as “performing the humor, absurdity, pain, and defiant critique of the camp, an ‘agent provocateur’” (64). How do you make these distinctions and why are they important to you (if I am right to claim that they are)?

Barbara Brickman (BB): Yes, those are my distinctions, and they are indeed important to me. Initially, I found it challenging to answer this question, but I’ve become better at it over time. I appreciate the distinction between camp as a creative practice for makers and camp as a reading practice for audiences. However, I also want to emphasize that camp exists as something within an object, read by the spectator or audience. For me, it started with identifying campy representations of female same-sex desire in the 1950s characterized by exaggeration and artifice, prevalent in sensational fiction and B movies like Daughter of Dr. Jekyll (1957, Dir. Edgar G. Ulmer), which we can read as camp because we see its bad acting, its failed seriousness, and we can get inside its representation as phobic, panicked representation of female same-sex desire.

As I delved deeper, I became more invested in uncovering lesbians who practiced camp in their lives and communities, who performed on stage with their friends. This extended to individuals like Tallulah Bankhead and Gladys Bentley, who were makers, actively creating camp experiences and performances, or people who – like Marijane Meaker – produced a disruptive and ironic and parodic denaturalization of normative culture. And so it became increasingly important to me to make a case for the practice of camp by lesbians – at least in this historical moment.

As for a definition of camp: there’s a couple of combinations which are central to me. If I’m going to talk about the camp as someone who practices then I think about this gay male cultural practice, predominantly gay male-coded signifiers, disruption of gender, double entendre, a wicked kind of retort or venomous undercutting of anybody who is a closeted or heteronormative.

And then for camp as a sensibility I always think of Esther Newton’s phrase of “incongruous juxtapositions” that tend to disrupt gender and sexuality. And I also love the idea of a failed seriousness that you perceive, but that you also love. Those are the ones that I hold onto.

And then I just think about RuPaul and that centers me again, because I’m around 18- to 25-year-olds a lot, and because Drag Race has been so popular in the US. Hence, when I tried to explain to them what this thing is like, I referred to the contestants on Drag Race and their sense of humor – painful, harsh, but really funny, and then my students get it. It is very similar to how Batman mainstreamed pop camp in the 1960s. RuPaul’s Drag Race is that mainstream camp text that rural Alabama kids have seen. That, and But I’m a Cheerleader (1999, Dir. Jamie Babbit) – that is another text that they know.

KH: But I’m a Cheerleader is a fantastic camp text! I want to pick up on one of the things you just mentioned in your definition, and which seems to me a crucial point of contestation among scholars of camp, namely the question of how camp relates to failure – be that aesthetic failure, a failed seriousness, or a mismatch between intent and result.

You address, among others, characters that are marked by the excessive failure to conform to matrimonial demands and heteronormative gender ideals. In contrast, in your analysis of the teen exploitation horror film Daughter of Dr. Jekyll you write that the movie “would not be fitting for a camp reading if there were not a seriousness that fails” (73). This seems to be a comment more in line with the “conventional” ways in which camp is connected to failure, but it is also one which seemed less relevant in other chapters. And while you stress through the book that you are interested in “lesbian camp, both intentional and unintentional” (3), I was wondering whether you could nonetheless untangle these different failures of camp and their intersections.

BB: It’s a really great question. It’s a really hard question. I think where I will go with that is thinking through the concept of marriage. Because the thing that occurred to me as I was writing this book over this long period of time, in terms of what was particular to the 1950s, was compulsory heterosexuality and that incredible imperative to marry. When you look at census data, they show that in 1948 about 96% of women and men of a certain age were married. This is such an important aspect of that historical moment. One of the things I realized after I wrote the book was that camp was a way to show marriage as a possible failure. Think, for example, of the kind of critique of marriage that was coming out of a show like Our Miss Brooks (CBS, 1952–1956), where Miss Brooks is the spinster, and the whole joke is that she’s never going to marry Mister Boynton. It becomes a joke on the show, in the press, from the producer of the show … you can’t have her marry. You find this theme throughout so many of these texts. Daughter of Dr. Jekyll has this adjustment therapy moment, where the doctor and the fiancé are literally saying to the young female protagonist: we have to drug you into sleep and force you into heterosexual marriage. That kind of pain is also central in Silver Age Wonder Woman, which circles around this enormous cartoonish idea that Wonder Woman is never going to marry Steve. And this is causing the both of them so much struggle, pain, and conflict. So one really important failure that camp creates concerns marriage in the 1950s, and the lesbian becomes this signifier of failure, but also an upsetting kind of signifier of success because she represents a different life, one that does not conform to this domestic containment culture.

When people misread camp, they think it’s this happy drag, this witty kind of ability to put somebody down, or this very empowering kind of drag mastery. But that misses the pain of camp. To me, and that’s the thing I always come back to: camp is drenched in love, it’s drenched in anger, and it’s drenched in pain. And if you miss that you don’t understand camp.

The camp is saying I have this power to disrupt normative culture, I have this power to take popular culture and to make something different of it, make it maybe even the opposite of what it wants to be, or what it thinks it is, but that action is rooted in pain, it’s rooted in what you perceive as your own failure or your own marginality from that normative culture. It’s therefore not surprising that I found failure across many, many of these chapters. I think it’s probably bleeding even into the way I understand a kind of butch sensibility, too, as rooted in a kind of pain and vulnerability that maybe it hasn’t had in evocations of it in the past.

KH: Let’s stay on the topic of pain for a moment. While it is hard to pick favorites, I was probably nodding most enthusiastically while reading chapter 2 on lesbian pulp fiction, and that is because you put into words what I have always felt to be true about these books and their continued fascination for contemporary readers, namely that they invite and allow an engagement with a painful past and with negative affects, particularly shame, for which there is otherwise little room in post-Stonewall queer culture. You write “The pulps … are more than bad objects of humiliation, despair, and vicious distortions smugly put in their place by postmodern irony and kitsch consumption. They still have an affective pull for contemporary readers that lies beyond irony, indeed beyond pleasure – at least partly in that same lowly realm of pain, self-loathing, and sad, traumatic alienation experienced by its original audience” (44). You also repeatedly stress that our post-Stonewall focus on progress was probably more hurtful than productive. For this argument, you’re drawing on scholars such as Heather Love and Christopher Nealon, among others. Did you come to their work through pulp or was it the other way around and you came to pulp through their work?

BB: I had read lots of pulp – a lot of Ann Bannon, maybe also Tereska Torrès’s Women’s Barracks (1950) – I love them because I do love sensational culture, I love B movies. I love trash. I love pulp. And then I was giving a paper on Daughter of Dr. Jekyll and in the Q&A someone said you need to read about shame. And so I read Heather Love [Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History, Harvard UP 2009]. I had read Nealon [Foundlings: Lesbian and Gay Historical Emotion before Stonewall, Duke UP 2001]. And I read other texts and I forget whose critique it was, but it concerned this idea that we’re so advanced, we’re so progressed beyond the 1950s that we can have this ironic distance from these pulp texts. Isn’t it pretty to think so?

I want to fight against this progressive, simplified narrative that the 1950s were one thing, and we’re in the 1990s or the 2020s, and we’re so much better, and we’re so much wiser, because I remembered the 1990s, when there were bags, and buttons, and magnets with pulp covers everywhere and that seemed disingenuous. And when I read [Heather] Love and Ann Cvetkovich [An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures, Duke UP, 2003], it just became increasingly clear that this idea that there was this bad, gay past – the 1950s as a kind of dark ages – is oversimplified.

That is something that always bugs me as a critic: oversimplified stories, where you create this scapegoat, or you create this boogeyman, and it doesn’t jibe with human experience. Similarly, I read all these accounts of women who had read the pulp, and they were repeating that shame again and again. That bugged me because I knew there’s pleasure here. There’s pleasure and pain. Yet even Marijane Meaker gave this account of how she lost her shame, how she ‘got politics’ and became properly identified with the positive narrative. But she’s reluctant. When I read that interview, I could feel the regret about the sense of humor that she had, this kind of bitter wit that was not self-deprecatory, but really self-loathing. In reaction to that I felt compelled to offer a more complex narrative about the 1950s as well as about our current moment. Living in the United States right now just makes you realize that the persecution of queer people never seems to go away and, therefore, a part of me thinks that negative affect, unpleasure is a part of life, and is going to be a part of people’s consumption and reading practices, probably forever. I don’t think anyone will read the pulps and not have a complex affective response to them.

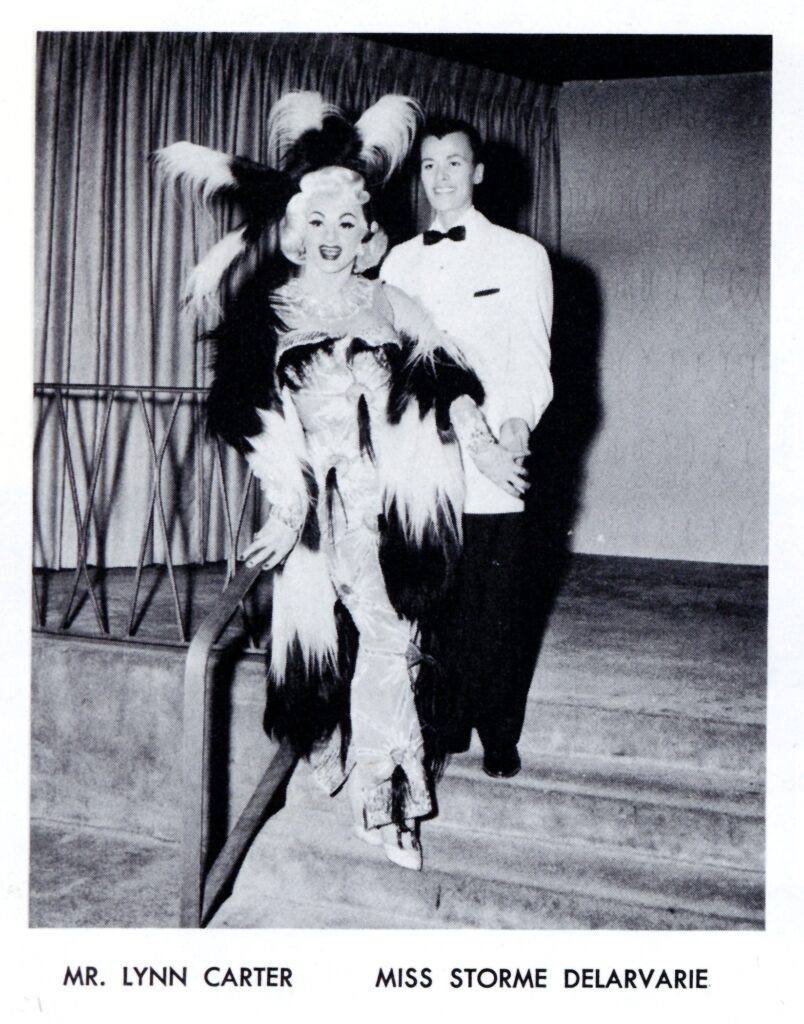

KH: Absolutely! I want to return to your earlier comparison between camp and butch sensibility, and thereby address the other big disagreement among camp theorists (besides its relation to failure and intent): its gender. At various stages throughout the book, you put the play with masculinity and butch personas at the center – among others in your reading of Tallulah Bankhead, your focus on Wonder Woman’s sidekick “Etta Candy,” your chapter on “butch comedy” in 1950s sitcoms with spinster protagonists, or – most clearly – in your final chapter on butch performers Gladys Bentley and Stormé DeLarverie. This focus – away not only from gay men, but from femininity – seems maybe the clearest deviation from how most people have written about camp. I am thinking, among others, of Clare Hemmings’ “Rescuing Lesbian Camp,” which ends by arguing: “‘Lesbian Camp’ – that is, the taking on of styles that uphold a masculine order, the embodiment of excessive immateriality, the refusal of gravitas; serious play with constructed superficiality. Who knows, eventually it might be possible to imagine such a masculine lesbian-camp subject too, but not just yet” (64).

That article is 16 years old now; however, and as you yourself acknowledge, it has become more “fashionable” in recent years to also see female masculinity as … well … fun (you point, among others, to a piece of non-scholarly writing called “Notes on Dyke Camp” from 2018). Would you say that your readings of the past have been influenced by this new “vogue” in contemporary culture – or are you simply happy that more people are finally catching up with what you have always known about butch comedy and lesbian camp?

BB: I’m certainly influenced by our current moment, but also influenced by the idea of an oversimplified sense of butch identity. I am indebted here to Sue-Ellen Case and Jack Halberstam and their push back on what butch can mean. One of the things I love about Stormé is that she says in Michelle Parkerson’s film Stormé: The Lady of the Jewel Box (1987), when asked, “Who are you? How should I address you?” Stormé says, “I’m me,” like this is who I am. This is who I’ve always been. So I very much wanted to open up a definition of butchness and of engagements with masculinity. But I think that is undoubtedly in the air. You know, it’s sort of funny to have lived through the moment where Judith Butler’s work was new. And then now, kids, when they’re 13, have absorbed this idea that was so bizarre when those texts came out. I also really think that so much of what Halberstam was saying all that time ago about female masculinity and what it means to present different masculinities, it’s in the water now, in a way.

A part of me also was really interested in thinking about how the lesbian camp’s use of masculinity is disrupting normative masculinity. Think of a performer like Eve Arden, who is not non-binary, but where there are multiple signifiers of femininity and masculinity, and they’re at play in that performance and changing the male characters around her. In the case of Daughter of Dr. Jekyll, too, I became increasingly fascinated by the fiancé, or in Wonder Woman with Steve. Because that’s something that I didn’t see people talking about, how in those texts, the butch performances by the central women dramatically disrupt normative male masculinity.

KH: One thing that struck me in your work is your interest in voice because it stands in contrast to so much else that has been written on camp, and which is usually focused on visual elements. This comes up in connection with the butchness and masculinity of Marlene Dietrich, Tallulah Bankhead, Ann Arden, as well as Stormé DeLarverie. Was that something that you wanted to explore from the beginning or did that only emerge over the course of your research? And are there maybe other non-visual markers of camp that deserve more attention?

BB: Okay, there are two ways to answer that question. I think that when voice became really important to me – it’s funny because I was writing about a radio show, and I didn’t think about it – was when I noticed that the reviews of Our Miss Brooks were obsessed with Eve Arden’s voice and they loved lemon metaphors: she was tart, she was lemony. And it’s not like she’s a baritone – she’s not Tallulah Bankhead, or that kind of hushed Marlene Dietrich – but still, they were obsessed with it, and then started to see it picked up in other places. And when I was listening to this episode of The Big Show with Marlene Dietrich, I was like, Oh, right! It’s not something that is discussed in terms of signifiers of lesbianness, not of these figures, anyway. So, voice came to me out of the research.

The other thing that occurs to me about that second part of your question, concerning other markers of camp that deserve more attention, is walk. I was having a conversation with a friend of mine yesterday about how there is a kind of butch walk, and it’s a signifier that people do mention, but there could probably be more examination of that, and I didn’t really do it. Again in Parkerson’s film about Stormé, there are many shots of her as the bouncer right outside the Cubby Hole. And there’s not only a stance, there’s a way she sits on the stool, the way she paces in front of the club, and it’s like a weird cowboy thing. She’s got a jean jacket on, and she’s got a gun in a holster on her belt, and a bow-legged kind of cowboy walk. I’m also really fascinated with cowgirls as camp in the early part of the twentieth and the nineteenth century, but that’s a whole different side project. But I probably could write a small piece on gate and walk.

One of the things I’m doing right now is thinking through what happened to lesbian camp after the 1950s. After you get out of the tunnel vision of research, as you start writing the epilogue, reviewers ask you and you ask yourself: where does this go? So I am thinking through how the lesbian camp gets hidden or disappears, gets ghosted in the 1970s and 1980s, and then comes back in this other form in the 1990s. Just out of my own curiosity I am looking at the early to late 1980s and I have seen still images of The Five Lesbian Brothers’ productions, and there’s a stance. If I could see them live, I would maybe be able to see that walk, and I’d love to be able to hear what their voice sounded like.

KH: As you’ve just mentioned the 1980s, can you say a bit more about what drives you to look at the past? You have obviously written about popular culture from earlier decades before, among others in your prior monographs New American Teenagers: The Lost Generation of Youth in 1970s Film (Bloomsbury, 2012) and Grease: Gender, Nostalgia and Youth Consumption in the Blockbuster Era (Routledge, 2020), and you touch on this question in the epilogue for Suffering Sappho!, which you just mentioned. There you cite Sue-Ellen Case, whose work you describe as “allow[ing] us not just a richer view of the past but also a stronger sense of a lesbian identity in the present” (178). In your introduction, you also point to your intent to “create a historical (and theoretical) foothold for lesbian camp and camping” (2). I was wondering if you could go into a bit more detail about the particular value you see in this kind of analysis of forms of media reception and representation from the past, and if you think the stakes are higher for queer history?

BB: They are definitely higher! I’m married to a historian. I am not a historian. I don’t play one on TV, but I think that my sense of the young people I’m around today is that they do not have a very good grasp of the past. I read Lesbian Death: Desire and Danger between Feminist and Queer (University of Minnesota Press, 2022) by Mairead Sullivan, and one of the things that I’ve become consumed with since I finished the book is this idea of the lesbian disappearing forever, that identity disappearing. And so for me, the stakes are very high because if you have a population of young people who don’t have a sense of the past and then also an identity that always has a sense of being disappeared, then I want them to know their past. I have a high school student I’m advising who’s doing her capstone project on Code-era lesbians, and she had never read Vito Russo’s The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies (Harper & Row, 1981) or Andrea Weiss’s Vampires and Violets: Lesbian in Film (Penguin, 1983). She was quoting something from 2012 and I told her that this person has no argument without Russo and Weiss! It is so imperative that young people have a sense of history, but also to let them know that this is an identity that is possible for them. Sullivan in her book stresses that this version of the lesbian feminist as somehow radical and no fun is being used by the right to disrupt, to cause conflict amongst us and to dismantle feminism. If I can possibly counter that discourse with the idea that there is this strong legacy of humor and critique and camp within a lesbian culture or community, then that’s what I’m going to do.

KH: Another way to connect to the past is nostalgia. You only explicitly mention the term two or three times in Suffering Sappho!, but considering your prior work and camp’s embrace of the “out of date” more generally, I still have to ask you: how do you think about the connection between camp and nostalgia, maybe also a specifically queer or reflective nostalgia (in the sense of Svetlana Boym)?

BB: One of the things that I love about nostalgia is that there’s pain and pleasure. And so, I think, we can see a theme developing across my works. I reject the oversimplification of nostalgia as necessarily reactionary or necessarily about elevating a better time from the past when that past moment might have been more politically advantageous to you. That’s not understanding nostalgia correctly.

I think it sounds strange to say, but … you could imagine someone having nostalgia for a very awful time. And I know that nostalgia can be reactionary, but it does not have to be. It also can be used in so much more complex ways. One thing that occurs to me from the book is that I was completely fascinated with this throwaway line that Lillian Faderman has about these groups of kiki lesbians who are having parties to listen to Tallulah Bankhead – 30 or 40 people! (see Brickman 32); I was like, you guys are having great parties, can I be at that party?

Fandom, fans, and audience have always been central to what I do, and part of the thing that fascinated me about that was this was in 1950 or 1951, when that show was on; it’s supposed to be the Dark Ages. This is a terrible time, the worst time. And yet I wonder about the nostalgia that they felt: what did Tallulah Bankhead represent in terms of nostalgia for a pre-war moment or for a different experience of sexuality in that kind of 1920s and 1930s moment when it was less visible, and maybe more rebellious. So while I know that nostalgia has its issues, I’m reluctant to not see it as a really useful, affective experience for someone and also a communal, effective moment for groups of people.

KH: In all of the six chapters you present this intricate interweaving of close reading, theoretical discussions, and archival research (e.g. newspaper articles from the 1950s or personal ephemera by some of the women you look at). Chapter 1, for example, opens with an in-depth discussion of the very different reactions to the release of the Kinsey reports regarding first, the sexuality of men, and then a few years later, in 1953, the Sexual Behavior of the Human Female. You use these as indicators of incongruous postwar sentiments around female (queer) sexuality. From there you develop your analysis of the impact that the large numbers of women serving in the military have had on queer representation in comics and on TV, which finally gets us to the heart of the chapter, namely The Big Show (NBC radio, 1950–1952) and Tallulah Bankhead’s camp persona. That is a lot of ground to cover, and lots of sources to keep in order and in balance. Would you say that this is typical for the kind of scholarship you produce or did this project demand different skills and approaches from you than your prior work?

BB: It absolutely necessitated a different approach for me. As I say, I’m not a historian – I am fully aware of this, because I know I’ve watched a historian at work for 25 years. I felt compelled to do my homework, let me say, and I think it probably shows a bit too much. But I felt compelled to get it right, because if someone is lost from history, you have an obligation to try to fill in that history. To say that I had never before written about a real person is just so rude to every actor and actress I’ve ever written about, but still; I was writing about their star personas. When writing about Stormé, I felt a different sense of responsibility to a human being who had lived a certain life, and who had been made into a legend – maybe not even of her own desiring, in a way. Stormé’s evasiveness about Stonewall is fascinating to me.

But I did feel compelled to do more work, and I also had the insecurity of a graduate student, which I shouldn’t have had because I was 20 years out of graduate school. But I had never written about television history, and so when I came to the Our Miss Brooks chapter, I may have been overcompensating: I read everything about the early period of television. I read also many, many, many books on radio. Similarly, I’d never written about comic books in my life and so I felt compelled to do it justice. Overall, I felt that if I’m going to take on these historians and say you all are leaving out this element of lesbian life, then I had to do as much work as I could to say I’m not just a media theorist who’s dabbling in history – I actually know this history.

But you asked about my working process, and it is 85% research. If you looked at the timeline, you’d be like holy crap, why is she spending six months researching when she writes for three weeks the paper that comes out of it? But that’s my process and I will sit and stare at a blank computer screen if I don’t feel like I’ve done all of that work. I often liken myself to Meryl Streep when I talk to my students about my writing process, which they always find humorous.

One of my fondest memories of graduate school is having the time to sit in the stacks. And I would just go for one book, then think, Oh, there’s Jacqueline Rose’s book that I was gonna get, and then would notice the books next to that, and I would sit and read the three or four books and I would be there for hours. That has not changed. But, additionally, I did feel compelled to do my due diligence.

KH: As has by now probably become clear to all readers of this interview, the range of material in this book is nothing short of impressive. The diversity of media and of contexts that you introduce into your arguments, the details of the close reading, there is just so much there. Which leads me to a couple of interconnected questions: Was there a particular text or object that inspired the book? How did you find the material? Were there any surprises in what you found and encountered? And was there anything you couldn’t include in the final manuscript?

BB: The origin story of this book is that I was giving a paper on Freaky Friday. That film and its star Jodie Foster make up much of a chapter in my first book, New American Teenagers. So I was giving this paper during a panel on youth film, and all three papers possessed a certain kind of humor. A person in the audience – this is at SCMS [Society for Cinema and Media Studies’ annual conference] in Atlanta, I believe – asked me, “Oh, so are you doing a camp reading, like, is Jodie Foster camp?” And I was like, “Huh, maybe?” Because in my mind, gay men camp, right? So I went and read a little more into camp, and I was like, “Oh, yes, this is what I do, this absolutely resonates with everything in my being.” And this is really true to my process: Somebody asked me a question, or I find something, and then I go and I read everything I possibly can about it. Because I feel like, oh, I don’t know this. I should go read 400 books.

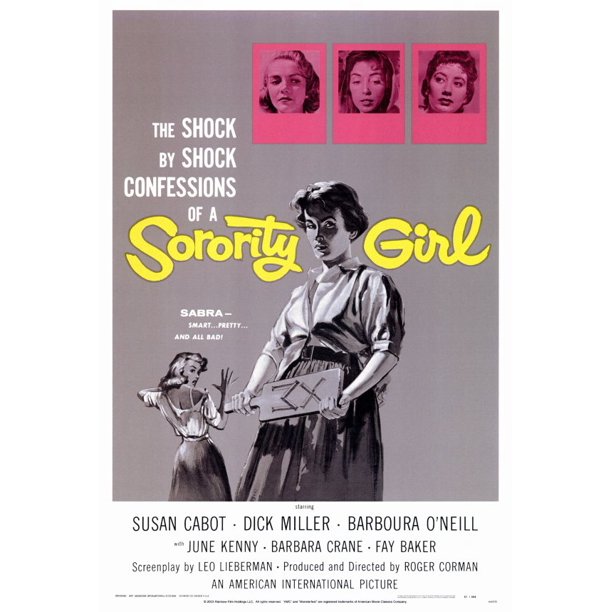

I had an article at the time on Daughter of Dr. Jekyll and it was just going nowhere, and I couldn’t figure out why I was so interested in Daughter of Dr. Jekyll, until I realized it was camp, and it was camp in a way that people don’t necessarily talk about camp. I became obsessed with Roger Corman and I really wanted to write about a whole series of those 1950s-exploitation films by Corman. And then something I read about camp made me re-read all those pulp novels, and once you’re talking about the pulps and exploitation films in the 1950s, then the other sensational popular culture things start to bubble up. For a month I was obsessed with Irving Klaw’s photographs of Betty Page. And then people asked me, well are you gonna talk about comic books? I started to go down that path. And then I met with a publisher who said, “Have you thought about television? You should have a chapter on television.” And so I went to one of my colleagues, Jeremy Butler, who is an expert in television, and I asked him, “If you were gonna do lesbian camp and television in the 1950s, what would you watch?” And he said, “Our Miss Brooks.” And I was like “Eve Arden’s in it. Well, yes, I will.”

KH: Who do you envision as the audience for this book? I am asking, because on the one hand, you offer these very sophisticated arguments regarding your intervention into how queer theory has conceived of camp – or more specifically, what it has missed not only in terms of lesbian modes of producing and appreciating camp, but where recent takes have unnecessarily and wrongly diminished or misunderstood camp’s importance as a strategy of survival, especially in repressive environments and moments of extreme pathologization. So that is heavy and theoretically dense stuff. But on the other hand, the book is also simply such a delight in terms of the archive of lesbian images that you bring into the spotlight. I, for example, immediately went to archive.org to listen to the flirtatious conversation on The Big Show between Tallulah Bankhead and Marlene Dietrich (references in chapter 1) and I also watched the episode of Private Secretary (CBS, 1953–1957), which consists of an extended spoof of Greta Garbo as a closeted lesbian (that’s from chapter 4). So it would seem to me that it also has this very popular appeal, and I am already thinking of several friends for whom this might be the perfect Christmas present, even though they are not in academia. Do you think of this more as your addition to understanding lesbian history, your contribution to a fuller understanding of camp, both … or something else entirely?

BB: I think this book, more than any other, has kind of changed who I think I could reach. I am the youngest of five kids, and I have three older sisters. I see myself in this position of, if only the older girls would think that I was great, I would be great. So, in my mind, my ideal reader is still those critics of feminist film theory and media theory that I’ve read and that I admire. But I was very, very conscious with this text of trying to write for more people, letting go of some of the jargon.

Part of the thing that’s happening to me now is that I realize that the post-life of the book and the way in which I can frame it online actually enables me to reach more people. I started making trailers. My kids taught me how to make trailers on iMovie. So I started a book trailer thing, and I looked it up. Novels and romance novels have book trailers. They’re beautiful. They’re the most magnificent camp product.

Additionally, when I wrote my introduction, even though it’s full of camp theorists, I very much wanted to write it in a voice that was less theory-heavy and generally I was working very hard to make the book more accessible. My hope is that a much broader audience will read some of it, engage with it and go down a rabbit hole and find out about Tallulah Bankhead and realize that there are so many ways to be the person that you are, that this is an option for you, and we should all be laughing as much as we possibly can, trying to find humor where we can, because I do think it’s important to survive.