Introduction

Janice Loreck’s Provocation in Women’s Filmmaking: Authorship and Art Cinema (Edinburgh University Press, 2023) sheds light on aspects of women’s filmmaking largely underdiscussed both in academic and wider circles: women’s engagement with provocative filmmaking, and woman qua provocateur. Loreck notes that “if the notion of the auteur tends to imagine the artist as male, then the provocateur does so to an even greater degree” (10), arguing that even since the time of Luis Buñuel’s famed eye-slice in 1929’s Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog), provocation in filmmaking has tended to be thought of within a highly masculinized framework. Thus, in a culture already primed to celebrate the titillation, shock, and discomfort of transgressive male directors such as Yorgos Lanthimos, Michael Haneke, and Lars von Trier, Loreck discusses the female provocateurs whose work is able to provoke through both familiar (and intensely unfamiliar) means.

Loreck details, through surgical analysis of a range of case studies, the works of female directors whose films dazzle in the diversity with which they challenge viewers. Some, like the works of Catherine Breillat and Claire Denis, obfuscate narrative pleasures through cinematic means that readers may identify as more “typical” to what one would imagine provocative filmmaking to be – sparse aesthetics and confronting imagery. In contrast, Athina Rachel Tsangari uses the realm of the bizarre and strangely humorous in order to confront her audiences. Importantly, what unites these incredibly varied texts, as Loreck points out, “is their willingness to engage with confronting images and subjects, and their invitation to us to do so as well” (19).

What Loreck is able to accomplish here then, through her insightful analysis of a melange of provocative works by female directors, is to provide an academic perspective on a painfully overlooked sector of women’s filmmaking. In spotlighting these particular texts, Loreck simultaneously confronts the reader with their own preconceived notions of what transgressive cinema can look like. In my conversation with the author, Loreck discusses the muddying of the concept of rape in mainstream films like Gone with the Wind and Rashomon, the peculiar process of learning femininity, and the mind-boggling comparison between Anna Biller’s Viva and Austin Powers.

Aimee Traficante (AT): So I guess I’d like to begin with the most obvious question, but one that I feel readers will find particularly useful, and that is your definition of provocation in filmmaking within the context of your book. I’m namely asking this question because of the experience I had before, and then after reading your book, where I felt that beforehand I had a pretty clear understanding of what provocation in filmmaking might look like. But then, intriguingly, what your book focuses on in terms of provocation in women’s filmmaking, altered my definition of what being provocative onscreen can look like. So within the context of your book and the films you discuss, how do you define provocation? Does that definition differ from how provocation in filmmaking is more broadly thought of by audiences and film critics?

Janice Loreck (JL): So in my book, I define provocation as the incitement of negative feelings in the viewer that are not experienced as pleasurable, enjoyable, that are primarily unpleasurable. So feelings like shock, a sense of discomfort, sometimes a feeling of being ethically compromised or challenged by the material. And what I mean by unpleasurable is that these films and the provocations that they enact are not like horror films, for example, where feeling terrified or afraid is actually part of the fan’s enjoyment of the film. So my book defines provocative films as those that break that unspoken expectation that films will be an enjoyable, pleasurable, or entertaining experience. And that’s an assumption that underpins a lot of viewers’ and critics’ engagement with cinema. So on top of that, I think provocation can take a few different forms. And I talk about this in the book as well. There are the types of provocation that involve what Asbjørn Grønstad calls visual transgressions, so graphic and shocking imagery or spectacle. And they can also include provocative cinema that involves more of an experiential provocation, of feeling disturbed, unsettled, challenged. Nikolaj Lübecker talks about this a little bit in his book on ‘feel-bad’ cinema, which he defines as cinema that doesn’t offer any catharsis. So I think provocation can involve different types of bad feelings and can be enacted in different ways. When I wrote my book, I mostly focused on that kind of either visual transgression or emotional discomfort. At one point, I did think about including a chapter in the book on the provocation of boredom, like in Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, for example. But in the end, I kind of kept the collection of films around ones that were dealing with questions of ethical representation, ethics around depictions of sexuality, femininity, or gender. So you asked about how my definition of provocation differs to how it might be used by critics or audiences more broadly. I think provocation has a lay meaning which is quite broad and flexible. But I do think that has become a bit of a cliche in a lot of film criticism for describing any film that seems to have an overt address to the audience, that is meant to challenge them, scandalize them, or make them uncomfortable. And it’s used very broadly in film criticism to refer to things like Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness, but also things like Marie Antoinette by Sofia Coppola. So it really can be used very broadly in criticism just to mean anything that might cause a negative reaction from a viewer.

AT: Anything slightly challenging.

JL: Slightly challenging, slightly scandalizing. Especially when it’s being used to refer to women. When applied to women, it usually describes sexual provocation or titillation or some kind of sexually explicit content.

AT: So at one point in your book, you argue that provocation can provide a “point of entry” into women’s filmmaking. So why then do you feel that provocation is a valuable starting point from which to “enter” women’s filmmaking?

JL: Partly because I hadn’t read any work that had considered women’s filmmaking from this point of view. I’d read work on women’s horror filmmaking, and I’ve written on women’s horror filmmaking as well. I think that there are some overlaps in terms of women creating transgressive content in the context of horror cinema. But I hadn’t really read anything that thought about women’s auteurism from the point of view of works that might be transgressive or might be overtly challenging to an audience. And that intrigued me because about ten years ago, there was a lot of scholarship about transgressive art cinema, such as the cinema of Yorgos Lanthimos or Lars von Trier or Michael Haneke. And whilst some women were considered within that grouping of new extremity and transgressive art cinema (i.e. Claire Denis and Catherine Breillat), the question of the intersection of transgressive art cinema and women’s filmmaking hadn’t really been addressed. And that struck me as an interesting oversight, because, as I talk about in the book, provocation is often discussed as quite a macho, masculine form of creativity. And this goes back to before the invention of cinema. It goes back to the avant-garde in the visual arts and in literary culture. And it continued into cinema culture where, you know, people like Haneke, von Trier, and Gasper Noé were described as these kind of macho, masculine provocateurs. And so in the end, I thought it might just be interesting and useful to think about, firstly, why don’t we think about women as provocateurs, and why aren’t they discussed as provocateurs as frequently in film criticism? Secondly, I thought, well, it might be interesting to ask what we can learn from looking at challenging works by women. What can we learn about provocation as a mode of film address more generally? And what can we learn about the work that women make and the form of creativity that women directors and their collaborators might bring to cinema?

AT: Yeah, that’s really interesting, because you do discuss how provocation in filmmaking is constructed as a hypermasculinized act. This occurs because of the perception of an inherent gender dynamic within the term provocateur, where the director is seen as this active aggressor enforcing their work upon the audience, and the audience is positioned as a passive subject. So that is why, as you say, the term has been applied to mostly male directors. So then, would you argue, that it was a goal of this book to incite a dialogue around who “gets” to provoke?

JL: Certainly that was one goal: to kind of bring to our consciousness the fact that the way we talk about the creativity of male auteurs and male creators is different to the way that we talk about the creativity of female auteurs and female creators, and that gendering creeps into our language. For example, in Patricia White’s book Women’s Cinema, World Cinema, she talks about how world cinema and art cinema directed by women is often marketed as a very humane cinema that tells stories of the human spirit. And whilst I love those sorts of movies, and I think that there is a huge value in that, it’s quite interesting that this idea of creativity being challenging and difficult and confronting doesn’t seem to be as discursively associated with women directors as much; thus, I wanted to talk about that in the way that we conceive of male auteurs versus female auteurs. But in the end, that goal opened up a number of other goals as well, such as, well, why would any creator want to make an audience feel uncomfortable, challenged, upset, or disturbed? And specifically, is there a reason or a purpose in which a woman creator might want to do this as well? And this is not to essentialize or homogenize women’s filmmaking. I think women’s filmmaking is incredibly diverse, but I think that we can discern trends in women’s filmmaking around the use of confrontation and challenge that can reveal a lot about the kinds of conversations women creators want to have and the types of experiences they want to communicate to their audience.

AT: Well, actually, speaking of trends, whilst you do cover an array of short and feature length films that each are unique in their depiction of provocative acts, there are, of course, these repeating thematic and narrative patterns that can be seen across several of the texts you discuss. One such trend is a repeated focus on acts of sexual violence against women. So, in regards to this, I firstly wanted to ask if you believe that audiences and critics are more likely to tolerate the depiction of such acts in films when they are in a film helmed by a male director as opposed to a female director, because, as you say, male directors tend to be revered as these “cultural mavericks,” whilst female directors appear to be judged more harshly. You actually provide a specific example in your book that occurred to Jennifer Kent at a screening of The Nightingale, which you analyse in your book. You mentioned that at the Venice Film Festival screening of her film, when Kent’s name came up in the end credits, a critic yelled out and called Kent a whore. There was speculation that this was due to her depiction of multiple rapes in her film. So again, would you argue that there is a discordance there?

JL: That’s a really difficult question to answer, because the way that sexual violence is depicted in cinema varies enormously. For example, the depiction of something like marital rape in Gone with the Wind is totally different to the depiction of sexual assault in something like Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible. So it’s hard to determine whether the gender of the filmmaker impacts reaction. But I do think that one of the largest determinants of audience’s reactions to depictions of sexual violence really comes down to graphicness. Because when we think about sexual violence in film, it is actually everywhere in cinema. For example, it is an enormous narrative event in something like John Ford’s The Searchers, and as I mentioned, it appears in Gone with the Wind. But in these sorts of films, it’s implied either through a fade to black or the camera cuts away and another scene begins.

AT: You also mentioned Rashomon.

JL: Yes, absolutely. Rashomon is sort of such a landmark film that is completely premised around the question of whether rape occurred or not. And we could also name something like Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad, another classic of the art cinema canon that absolutely centers the question of whether rape happened or not as part of its narrative. And Dominique Russell has edited a really interesting book called Rape in Art Cinema, which talks about how rape is often positioned as an ambiguous event in art cinema. And she heavily criticizes this tendency. But returning to your question, I think that certainly when women are the chief creative force behind a depiction of sexual violence, in recent years, the question of the author’s gender has come into the conversation. For example, there were a number of op-eds in places like the New York Times and the Guardian that considered whether it makes any difference if it is a woman authoring these depictions of sexual violence. I’ve read these op-eds and they generally don’t arrive at an answer, I think, because the ways in which sexual violence is represented and its meaning and impact is so dependent on questions of graphicness, duration, repetition, and also the broader context of narrative framing and characterization. That’s why it’s so hard to arrive at a singular answer around the ethics of depicting sexual violence, because there is such variability in how it might be treated in a film.

AT: The two films that you do discuss most thoroughly in relation to their portrayal of sexual violence on screen, Isabella Eklöf’s Holiday and Jennifer Kent’s The Nightingale, whilst each taking differing approaches to the actual depiction of the acts themselves, share a desire to confront their audiences by forcing them into a prolonged look at rape scenes. Which, again, goes back to what you were just saying about how rape typically tends to be treated somewhat ambiguously. So could you talk a little bit about how these techniques, though distressing, do align themselves more broadly with feminist theories regarding the depiction of rape and sexual violence on screen?

JL: Yeah, absolutely. I do think it’s important to first point out that these films don’t necessarily force the viewer to watch it. It’s true that cinema, more than any other medium, perhaps does control what a viewer does and doesn’t see, and the intensity to which they do or don’t see it. But it is important to acknowledge that viewers do have a choice to enter into that viewing relationship, and they absolutely have a choice to leave and they exercise that choice. Plus, Eklöf and Kent have both been very open and acknowledging of the fact that people might not want to sit through those scenes. So I think it’s important to point out that there is ultimately a choice as to the degree of their engagement, even though viewers might be considered passive by some film scholars. But coming back to your question, what I argue that these films are engaging with is a feminist school of thought which says that there’s sexual violence that women experience every day which should be acknowledged and confronted, and, yes, sometimes depicted. And that could be in the visual arts and in the literary arts and in cinema. Now, this isn’t an uncontested point of view. It absolutely has been contested. There is another feminist line of thinking that all depictions of sexual violence and rape are objectionable and problematic, because even if they’re fiction, and even if they’re created to denounce the sexual violence that women experience, they’re still adding to the imagery of violence against women in the world. And that therefore, there should be a cessation, a moratorium on this type of imagery. But the other school of thought, which Kent and Eklöf and other women artists have adhered to or aligned themselves with, is that it’s important to speak truthfully about the realities of sexual violence, and in some cases, that does involve depicting it. And Isabella Eklöf, the director of Holiday, which is one of the key case studies in my book, she says that she feels a need to show all aspects of life and all aspects of women’s lives. And she says she wants to show the “shit that’s supposed to stay hidden” in women’s lives. And she includes sexual violence amongst that. And there have been examples of women artists who agree with that position. For example, Ana Mendieta, the Cuban-American artist, made an incredibly famous performance art piece called “Rape Scene” in the 1970s, where she posed as a victim of sexual violence. And also we could include films like Coralie Trinh Thi and Virginie Despentes’ Baise-moi. The approach of showing this violence is particularly relevant in the context of cinema because, as I mentioned earlier, sexual violence is often tastefully hidden. There’s a fade to black or there’s a cutaway. You could almost forget that sexual violence has even happened in these films. So in this context, you can understand why filmmakers like Kent and Eklöf might decide that for them, the more ethical choice was to actually confront the violence that their characters have experienced.

AT: Especially when you consider rape scenes like the one you mentioned in Gone with the Wind, where it cuts to black, and the next scene is Scarlett looking very happy and satisfied. It really dilutes what happened previously.

JL: Absolutely. And it also introduces an element of ambiguity about the nature of what we saw. Some reading this interview might remember that scene differently and think, I didn’t see sexual violence happening there. I saw something else. And that ambiguity becomes productive because it kind of allows a questioning of issues of consent. And so feminist filmmakers, women filmmakers, might wish to eradicate that entirely by actually showing how things unfold. And again, of course, it’s hard to watch, but Isabella Eklöf’s film Holiday shows how a playful encounter between the protagonist and her boyfriend kind of evolves or devolves into something much more violent. And that is also part of her feminist engagement with the issue of violence on screen: to show how consent can be withdrawn in an encounter between two people.

AT: Absolutely. So another theme of your book that I did find particularly fascinating was your discussion of the intersection between provocation and pretty aesthetics, because, as you say, provocation in filmmaking does tend to be thought of within these very kind of limited parameters that align themselves with masculine aesthetics and gratuitous spectacles. So I was wondering then, if that was part of your motivation for including the works of Lucile Hadžihalilović and Anna Biller within the scope of your book: to provide an alternate view of provocation in filmmaking that aligns itself with more feminine aesthetics.

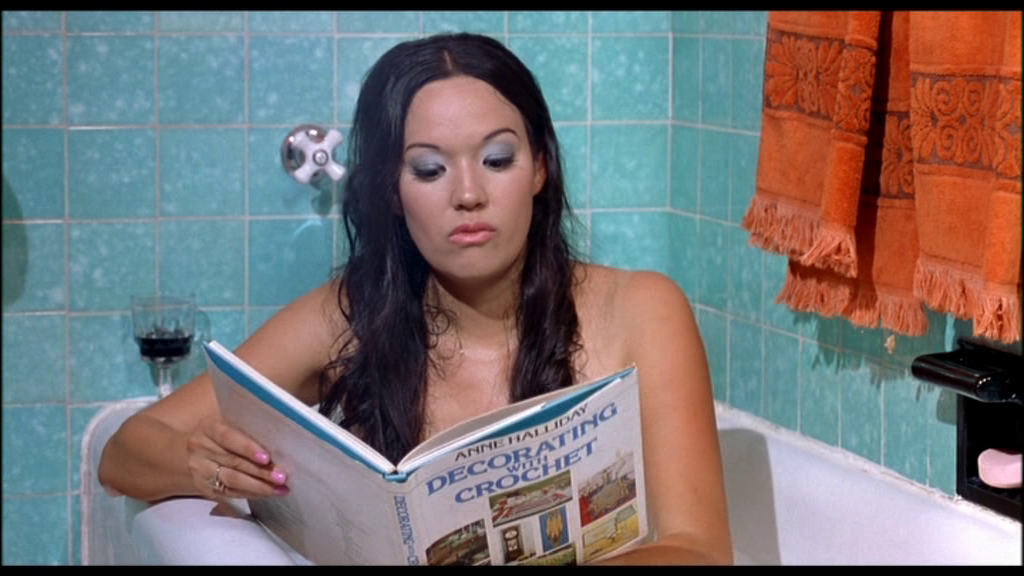

JL: Yes, I absolutely wanted to include their works because, as you just mentioned, there is certainly a set of aesthetics that have come to be associated with provocative, challenging avant-garde work. In fact, one of the sources that I talk about in my book refers to it as the “spiky” avant-garde. This is the idea that the avant-garde should be confronting and challenging and difficult, and also ugly, and that its ugliness is complementary to its intellectual and aesthetic challenge to the viewer. So, yes, I did want to include Lucille Hadžihalilović and Anna Biller, partly to talk about the ways in which you can provoke an audience through many different means. Whilst filmmakers like Catherine Breillat and Claire Denis, for example, do use gratuitous or sometimes even ugly images to provoke, some filmmakers go down a different path, such as Hadžihalilović. She is an incredibly accomplished filmmaker who makes very composed, almost painterly films that are stunningly beautiful to watch. But when you watch these movies, you realize that they’re incredibly sinister, or at least they feel like something sinister is happening. It’s never quite clear what’s going on, and that really fascinated me because it’s almost as if the beauty of the images lures the spectator into a kind of aesthetic pleasure and enjoyment, but then undermines or corrupts this enjoyment by introducing uncertainty about what’s actually happening. Hadžihalilović’s films typically are about child protagonists in situations where they may or may not be in peril. They’re a bit like old fashioned fairy tales, where these young children are surrounded by adults and the children might need to escape from the adults because they might have sinister intentions. And this can be very difficult to watch sometimes, because, of course, as viewers, we don’t want to be enjoying a film where children might be in danger. I should mention that a lot of the time the danger of the children is not really spelled out, particularly in a film like Innocence, her debut feature length film. It’s not totally clear what’s actually happening there. Anna Biller is slightly different again because her films usually adopt an aesthetic that we might consider to be retro and sometimes even campy, even though I argue that, at the end of the day, they’re actually not campy at all. They’re quite serious and sincere in their depictions. But the thing about Anna Biller is she absolutely expresses that. She wants to give visual pleasure to the viewer. She wants to create beautiful images, but her films are serious engagements with questions of women’s sexuality and also women’s desire for romantic love. And they’re quite sad and pessimistic stories for the most part, about how women have such longing for sexual connection and romantic connection, but are consistently denied that by men. And so even though they have this joyous, beautiful, nostalgic aesthetic, they’re actually not tongue in cheek, they’re not camp. They have very serious discussions about heterosexual women and heterosexual women’s disappointment.

AT: Speaking in particular on Biller’s work, would you then say that there is the tendency to locate her work within the realm of ironic camp due to a perceived incompatibility between her film’s aesthetic choices and the narratives, which, as you mentioned, often do focus on dark subject matter? I’m largely situating this question within how I see Biller’s The Love Witch specifically discussed online. Because I would say that of all the films you discuss, The Love Witch is probably the one that has amassed the largest presence online, with many lines of the film’s dialogue being included in popular TikTok sounds and the beautiful visuals often being included in aesthetic film compilations across social media. And yet again, as you say, what people are mostly focusing on is the glamorous nature of the film’s protagonist, Elaine, and her witchcraft, and ignoring Biller’s very serious lamenting of the incompatibility of women within the matrix of heterosexual love.

JL: That’s so interesting because I had no idea that it had been taken up on TikTok. I didn’t consider that. Well, at least perhaps it wasn’t a thing when I was writing my book. So you don’t think the fans understand the gravity of what’s happening in the movie?

AT: The Love Witch is treated online largely as just a very beautiful looking movie. Elaine is depicted as a “girl boss,” for lack of a better word. Also, the sound bites that are used on TikTok are very isolated with no context, so yes, she is presented like she’s very independent and a bit of a “badass” character. So I would say that people view her as a very strong, flawless character with no vulnerability.

JL: That’s amazing. And on one hand, I think that films are what viewers bring to them. I don’t want to say to those users that they are wrong in their interpretation of the movie, because, of course, every movie facilitates a range of identifications and uses, and The Love Witch absolutely is a beautiful movie. And in many ways, Elaine is an incredibly powerful figure. And I can absolutely see why that would resonate with so many viewers. I think what I wrote about in my book was the fact that critics like Mark Kermode directly described the film as rife with camp and suggested that there was a degree of irony in the film, when in reality the film is, I think, not ironic. I think it is quite serious in what it says about women’s romantic disappointments, even as it relishes and enjoys this beautiful retro aesthetic. I think there is a desire to interpret Anna Biller’s films as ironic because they are so dark. I think irony protects us from actually feeling the depth of sadness and disappointment that she incorporates into her movies. And so we see irony instead of sincerity.

AT: And I think, I guess it also probably comes from a place of wanting to “place” and make sense of Biller’s work, because if there is this perceived incompatibility where her visuals are so stunning, yet the subject matter is so dark, to instead say, “Oh, she’s doing a Russ Meyer homage” is easier, I guess.

JL: And we’ve been trained to look for irony. This is a bit of an older example now, but I remember when Viva came out, Biller’s first feature, and, you know, it wasn’t so long before that, that Austin Powers came out. And Austin Powers is very much a film that is sort of lovingly poking fun at that era of cinema, that era of fashion. And so I think audiences were so used to seeing irony, so used to seeing spoof, that that’s what they saw in Viva.

AT: That’s really interesting because narratively, they’re kind of worlds apart.

JL: Completely worlds apart, yes. Although I do love Austin Powers as well, I will say.

AT: True, it is great. So another theme that your book deals with, and that is shared by a number of the films you discuss, is the kind of turbulent transition of entering womanhood and the kind of awkward, ill-fitting attempts at trying to learn an idealized femininity. Could you speak a little on this idea as it relates specifically to Athina Rachel Tsangari’s The Capsule, and how that film provokes in its kind of denaturalizing of elements of femininity often thought to be “instinctual”?

JL: The idea of coming of age and the awkward transition from girl to woman is such a rich terrain for women filmmakers, and it’s been dealt with in so many ways. Some of these films are charming and lovely, and some of them are deeply dark and disturbing. I think one of the most common observations about coming of age is that femininity is not natural. It is something that is enforced upon women, often with very brutal and blunt measures. For example, through acts of shaming of women who do not conform to expectations of femininity. So it makes sense that such acts come up in women’s filmmaking. It’s essentially an interpretation of Simone de Beauvoir’s statement that one is not born, but becomes a woman. So I talk about a few films that do this, for example, She Monkeys by Lisa Aschan and Fat Girl by Catherine Breillat. But, yeah, Tsangari’s The Capsule is another iteration of the “becoming a woman” story. The Capsule is an interesting one because it’s a short film, and it was commissioned by Deste Fashion Collective. And essentially, the commission is that an artist, in this case Tsangari, is invited to respond to some fashion pieces and respond to them in a way that illuminates the function and beauty and artistry of fashion. And so that’s how The Capsule came into being. And essentially it’s a very strange, gothic, and surreal short film about a castle on a rocky cliff. And one stormy night, a number of women mysteriously come to be in the castle, and as they come into being, they are welcomed by the mistress of the castle. It turns out she’s an immortal being. Her job is to train these women into becoming women and to ultimately replace her as the immortal mistress of the castle. And what follows is a number of very strange, bizarre sequences where they’re taught to wear lingerie, to walk in heels, to dance. They walk around the castle grounds wearing these beautiful couture outfits. And essentially they are being taught to become like her, like the goddess. This film uses kind of very dark, surreal humor in order to express this process of becoming woman. And it is very funny. Funny, but also confronting to watch because the women hiss at each other like insects and animals. And I argue that this kind of provocation and sense of estrangement that this film produces is actually a form of commentary on the weird things that women have to do in order to become gendered as women. And it is a very intense and exaggerated process of estrangement from these acts and these behaviors that women are expected to adopt in order to qualify as real women. And The Capsule uses the techniques of surrealism and the uncanny to make this commentary.

AT: And I think it’s really interesting that the origin of this short film is its commission from a fashion institute, which is an industry that is responsible, in part, for the prolonging of this idea that certain feminine qualities have to be embodied in order to be considered a woman.

JL: Yes. Yes. And there are fashion objects in The Capsule that really are not functional as fashion objects. So, for example, shoes that are impossible to walk in, or outfits made entirely of human hair or light bulbs. And on one hand, I love it because the clothes become an art object and the woman’s body becomes a canvas for these beautiful fashion objects. But at the same time, the clothes are mobilized from this commentary about the impossibility of ever fulfilling the idealized image of womanhood. How can you fulfill an idealized image of womanhood if you can’t even walk in her shoes?

AT: That’s so interesting! And finally, there’s a quote in the conclusion of your book that reads, “it can be uncomfortable watching films about women’s lives because women’s lives are uncomfortable.” What do you believe then, ultimately, is the value in women continuing to create provocative films, both in terms of engaging in taboo subjects and in engaging in assumptions regarding provocation in filmmaking itself?

JL: So that quote is adapted from Maïmouna Doucouré, who is the director of Cuties. I don’t talk about Cuties at great length in the book, but I do mention it in the conclusion. You might remember that Cuties is a French film and it was the subject of controversy in 2020. Essentially, it’s about eleven-year-old French girls who get together and form a dance troupe, and they copy the dance moves of adult women that they see on tv and on the Internet. This film became the center of a huge controversy in 2020 because Netflix advertised the film using a poster that some argue sexualized the child actresses. This controversy spiraled out of control. Netflix replaced the poster, but it was also featured on a Reddit forum that was implicated in the QAnon conspiracy theory. And there was a lot of hate directed at Doucouré. Essentially, Cuties was a coming-of-age film about being a young French Senegalese girl in contemporary France. Doucouré wrote a beautiful response to the controversy in the Washington Post. And she said, “some people have found certain scenes in my film uncomfortable to watch. But if one really listens to eleven-year-old girls, their lives are uncomfortable”. And for me, this really summarized so beautifully one of the prevailing reasons why filmmakers in my book make these unsettling and disturbing films. Because there is so much about women’s lives that is uncomfortable and still unacknowledged. And partly that is to do with women’s humanity. Being human is uncomfortable. We have beautiful dreams and fantasies, and we also experience terrible realities and horrific nightmares. And certainly women have their share of those experiences, too. I think it’s incredibly valuable that cinema addresses this. In fact, I would say that cinema is one of the most important places for women to address the whole gamut of human experience, from our dreams to our nightmares. I know that cinema is a hyper commercialized, mass media entertainment. In many cases it’s there to make enormous, mind-boggling profits. But at the same time, it’s a really valuable place for telling stories about our shared humanity and also the experience of living and being a woman in this world. So that’s what I really wanted to emphasize in writing this book. I think provocation can often be understood as a bad faith exercise. (In fact, it often is a bad faith exercise that is there to generate headlines and to create a perverse form of marketing for a film.) My book is about provocations that are, instead, important to hear and provocations that emanate from women’s creativity and from their lived experience.

Sign up for NRFTS alerts so you’ll know when future articles become available, and enjoy this related read:

Chelsea Birks, Body problems: new extremism, Descartes and Jean-Luc Nancy