Near Dark (BFI Film Classics)

by Stacey Abbott, London, British Film Institute, 2020, 104 pp., £10.79 (paperback), ISBN 9781911239277

Reviewed by Carl Sweeney

Compelling arguments can be made that several of Kathryn Bigelow’s directorial efforts merit inclusion in the BFI Film Classics book series. Whilst critical and commercial successes such as Point Break (1991) or The Hurt Locker (2008) may seem obvious contenders to receive such attention, Stacey Abbott (2020) focuses instead on the director’s first solo feature, Near Dark (1987).[1] For various reasons, including a recurrent tendency to reconfigure traditional genres, the notion of what constitutes a typical Bigelow film is a challenging one. Nevertheless, Near Dark can be understood, in some ways, as one of her most atypical works, because it represents her most sustained engagement with the conventions of horror. If this makes the film something of an outlier in Bigelow’s canon, its horror aspects provide the primary impetus for Abbott, who contends that Near Dark warrants close analysis as an example of a transgressive vampire narrative. This point is convincingly argued throughout the book, which is indispensable to anyone interested in Bigelow’s film.

In the opening chapter, Abbott deftly sketches in the circumstances surrounding the film’s production and reception. Near Dark had a complicated journey to the screen, shaped by issues including an enforced late change of shooting location, a demanding filming schedule and distribution problems. On release, its box-office takings were disappointing, although it received some positive critical notices which served to frame Bigelow as an exciting directorial prospect. Meanwhile, a 1988 screening at New York’s Museum of Modern Art further contributed to a sense of her as a potentially significant auteur and served as an early marker of Near Dark’s post-release reappraisal. Alongside her engaging discussion of such factors, Abbott also locates the film within the specific context of the 1980s, which ‘marked a notable return to the vampire in American horror cinema’ (2020: 6). By authoritatively comparing Near Dark with other contemporaneous films such as The Lost Boys (Schumacher, 1987), Abbott provides a useful contextual frame through which to situate Bigelow’s efforts. At the same time, this early section also establishes the book’s recurrent concerns, including the film’s blend of genres and its rich stylistic design.

This latter point forms the basis for the second chapter, which concentrates on the film’s aesthetics. In essence, Abbott argues that Near Dark’s distinctive visual and aural design serve to connect its classic horror trappings and its status as an unusual vampire narrative, with the film achieving ‘a cinematic Gothic aesthetic’ (2020: 16) despite the omission of traditional iconography such as garlic and crucifixes. This is ascribed, in large part, to cinematographer Adam Greenberg’s skilful chiaroscuro lighting, with the close analysis of the motel shootout serving as persuasive evidence that the film’s frequent interplay between darkness and light is a significant facet of its distinctiveness. A balance between competing factors is also relevant to Tangerine Dream’s score for the film, with Abbott noting that the music imbues Near Dark with an ambivalent, mystical quality. In her view, the film’s visual and aural qualities provide an appropriately modern Gothic ambience that facilitates an amalgam of generic conventions.

Further expansion on this point emerges in the third chapter, which examines the film’s action sequences within the context of other vampire narratives and 1980s cinema in general. Abbott considers Near Dark as unique in that it ‘takes the potential for violence that underpins the vampire figure itself and projects it outward in a series of explosive and visceral action set pieces’ (2020: 30). More broadly, she identifies the film’s bloodiness as a facet of the dialogic relationship Near Dark establishes with other 1980s action films such as The Terminator (Cameron, 1984), with the extended analysis of the roadhouse slaughter scene being one of the book’s highlights. Abbott also pinpoints other factors that are pertinent to the film’s status within the broader tradition of action, including the use of humorous wisecracks that enhance the presentation of the vampire characters as ‘dangerous but alluring’ (2020: 50).

The dual nature of the vampire is considered further in the fourth chapter, which provides a close reading of the character of Mae (Jenny Wright). Although observing that Caleb (Adrian Pasdar) seems to fit the broader template of the sympathetic vampire protagonist, Abbott proposes that it is, rather, Mae who represents a significant example of this trend. However, she does not embody this character archetype in every respect, due to her lack of self-loathing and the pleasure she takes in killing. Therefore, Mae’s complexity ensures that she is illustrative of ‘the coexistence of light and dark that defines the film’s Gothic aesthetic’ (Abbott, 2020: 53). Furthermore, the careful analysis in this chapter reveals how the character, like other women in Bigelow films, frequently challenges gender stereotypes. For instance, Abbott comments incisively on how Mae both personifies and runs counter to the tradition of the femme fatale, with factors such as her androgynous appearance ensuring that she stands as a counterpoint to more familiar representations of such figures. Accordingly, the chapter argues that Mae is difficult to label with certainty, and that she represents ‘a distinct moment in the trajectory of the female vampire’ (2020: 62). This is indicative of the successful overarching contention of the book, namely that Near Dark is a transgressive film.

In the final chapter, this point is argued in relation to criticisms of the film’s apparent conservatism. Upon release, some reviewers commented disapprovingly on the ending, which can be read as reaffirming traditional values, whilst the narrative ‘cure’ for vampirism was also seen to carry troublesome associations in light of the AIDS crisis. Abbott acknowledges that these perspectives are relevant, before offering a reappraisal founded on elements of the film that can be read as disrupting such criticisms. For instance, she problematises the film’s attitude towards the institution of the family and highlights how the generic interplay with the western can be seen as undermining older traditions such as that of the ‘captivity narrative’. Most persuasively, Abbott draws out the ambivalence of the final scene, which concludes on an ambiguous freeze-frame image and raises more questions than it resolves.

Overall, the book demonstrates credibly that Near Dark ‘transgressed and reshaped generic, aesthetic and cultural boundaries’ (Abbott, 2020: 86). Consequently, it represents a valuable resource for several groups. It is accessible and concise, so it will be worthwhile reading for general cinephiles who admire Bigelow’s film. For students and researchers interested in cinematic vampire narratives, this is an impressive addition to Abbott’s other works in this field. Finally, any future scholarship about Near Dark specifically will be obliged to consult it as a key text, since the analysis contained within is consistently illuminating.

[1] In 1981, Bigelow co-directed the arthouse biker film The Loveless with Monty Montgomery.

Available through Bloomsbury Publishing and booksellers

Read Carl Sweeney’s article “Kathryn Bigelow as a Neo-Star Director”

Special Issue (19.3) Fall 2021

Guest Editor Frances Pheasant-Kelly

Introduction, “Innovating the Frame: Kathryn Bigelow in Close-Up”

Excerpt: The essays here propose to address specific aspects of [Bigelow’s] films in ways not previously examined. These include her preoccupation with aesthetic spectacle, visual cartographies and formal framing techniques; an approach to characterisation through a ‘poetics of obsession’; a reframing of her directorial status as a ‘neo-star auteur’; the projection and reception of Bigelow herself; and a consideration of her films as controversial and propagandist.

ARTICLES

The Poetics of Obsession: Understanding Kathryn Bigelow’s Characters

By Christa Van Raalte

Megan Turner (Jamie Lee Curtis) in Blue Steel (Bigelow 1990)

Excerpt: “The obsessive commitment of Bigelow’s heroes can be said to fuel both the stylistic excesses that hold the spectator at a reflexive distance and the diegetic excesses that mark her characters, challenging the spectator’s allegiance. Blue Steel makes explicit the relationship between commitment and obsession, on the one hand clearly distinguishing between them by associating them with the hero and villain respectively, yet on the other hand repeatedly aligning them both visually and in terms of the narrative.”

Variations on ‘The Lonely Walk’ in the Films of Kathryn Bigelow

By Thomas Britt

The Lonely Walk in The Hurt Locker (Bigelow 2008)

Excerpt: “While much of the existing scholarship employs a metatextual view of this nexus, between Bigelow embedded within a rigid Hollywood system and her characters embedded within stultifying and distorting cultural/political systems, my goal is to illustrate the ways in which Bigelow and her characters reject externalities for the sake of the immediate mission, interacting with the physical space in which they make life-and-death choices that reveal their inner selves.”

Sway of the Sea: Kathryn Bigelow’s Imperial Eco-Eschatology

By Benjamin Halligan

Testing by Nature in Point Break (Bigelow 1991)

Excerpt: “My intention is to scope Bigelow’s soft or nascent fascism through a textual consideration of how she sutures ideas of destiny between man and landscape. Finally, and to return to her more recent work, the article then turns to the expression of this philosophy to brazenly imperial ends in Bigelow’s Last Days (2014).”

Zero Dark Thirty, Maya, and The Myth of the Calydonian Boar

By Kirsten A. Adkins

Looking from the Outside (Zero Dark Thirty, Bigelow 2012)

Excerpt: “Traces of Atalanta’s story can be found in Bigelow’s treatment of Maya. Like Atalanta, she is responsible for locating and targeting the enemy. Yet her successes are largely uncelebrated, and she is often rewarded for being ostracised by her male colleagues. Atalanta’s story provides an aesthetic patrimony or cultural template that repeats and reinforces hegemonic stereotypes predicated on a fear and mistrust of women’s inclusion in the fraternal unit.”

Kathryn Bigelow: New Action Realist

By Vincent M. Gaine

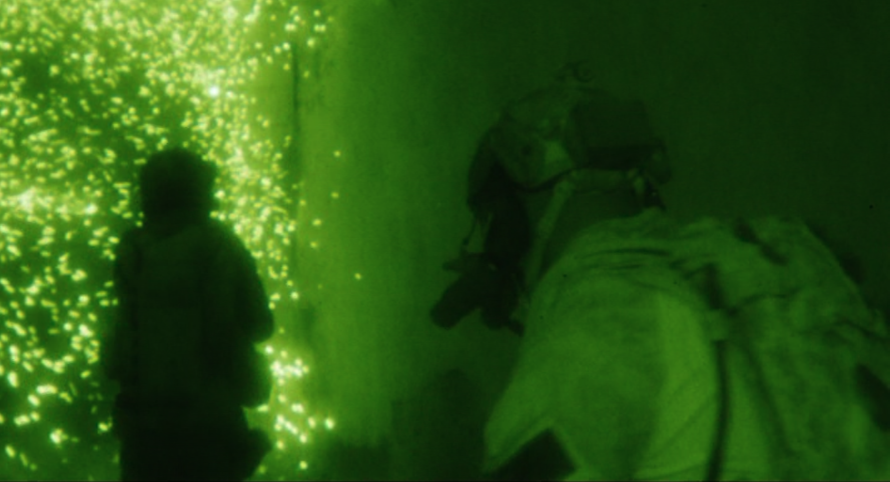

Night Vision Attack in Zero Dark Thirty (Bigelow 2012)

Excerpt: “This is a distinctive aspect of Bigelow’s place within new action realism – narratives are left unresolved and goals unachieved… Bigelow openly presents a contradiction: the viewer participates in the action but does not understand it, the film presenting an inexplicable experience in minute detail that should allow understanding, and yet does not.”

Kathryn Bigelow as a Neo-Star Director

By Carl Sweeney

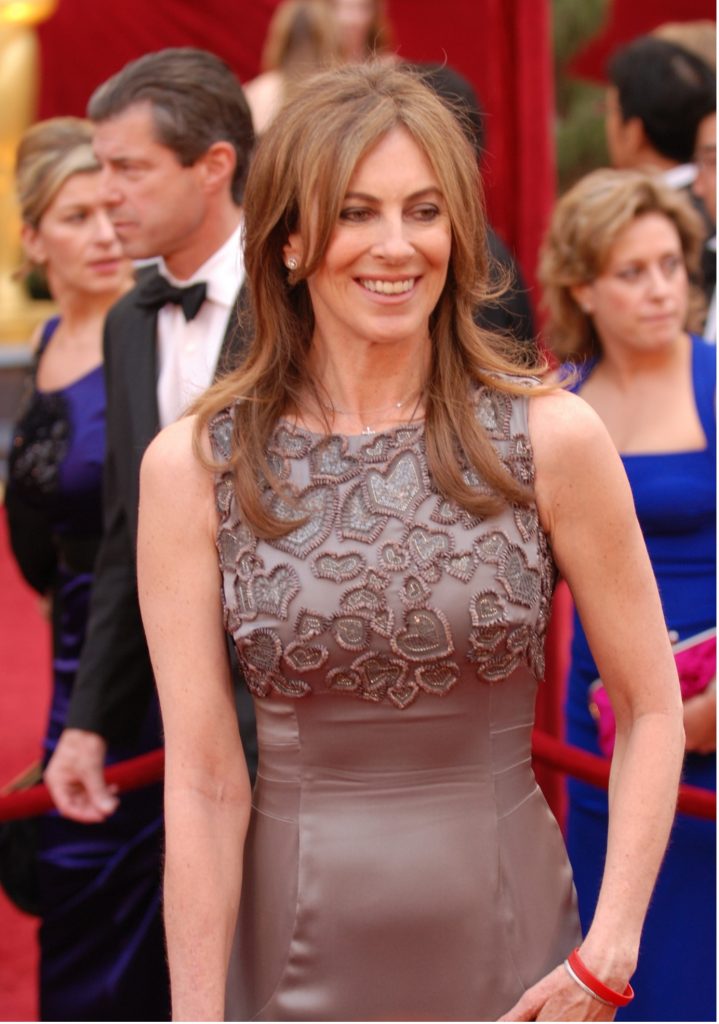

Kathryn Bigelow: Director as Neo-Star

Excerpt: “Bigelow’s short documentaries represent an extension to her other work concerning terrorism. I Am Not a Weapon (2018), for instance, sees her and journalist Dionne Searcey co-direct nine videos featuring female survivors of terrorist acts carried out by the Nigerian group Boko Haram, as part of a campaign made to tie in with the United Nation’s International Day of the Girl. In each segment, a woman speaks plainly and powerfully about her life, her experience of being captured and her hopes for the future.”

How does she look?: Bigelow’s Vision/Visioning Bigelow

By Deborah Jermyn

Visioning Bigelow (2010 Academy Awards)

Excerpt: “Bigelow’s distinct brand of edgy but desirable, and, it must be recognised, white femininity has been instrumental in her admission to what remains principally a ‘masculine’ club…this article draws on a cultural breadth of print media coverage of Bigelow from the broadsheet press to women’s magazines, focusing largely but not only on the post-The Hurt Locker period, in order to anatomise the nature of Bigelow’s visibility in public discourse. In doing so, its purpose is to examine how questions of ‘vision’ have long been and continue to be central to understanding Bigelow’s meaning(s) and circulation in film culture and the wider public sphere.”