By Alyxandra Vesey

Side A: Negotiating Canonicity

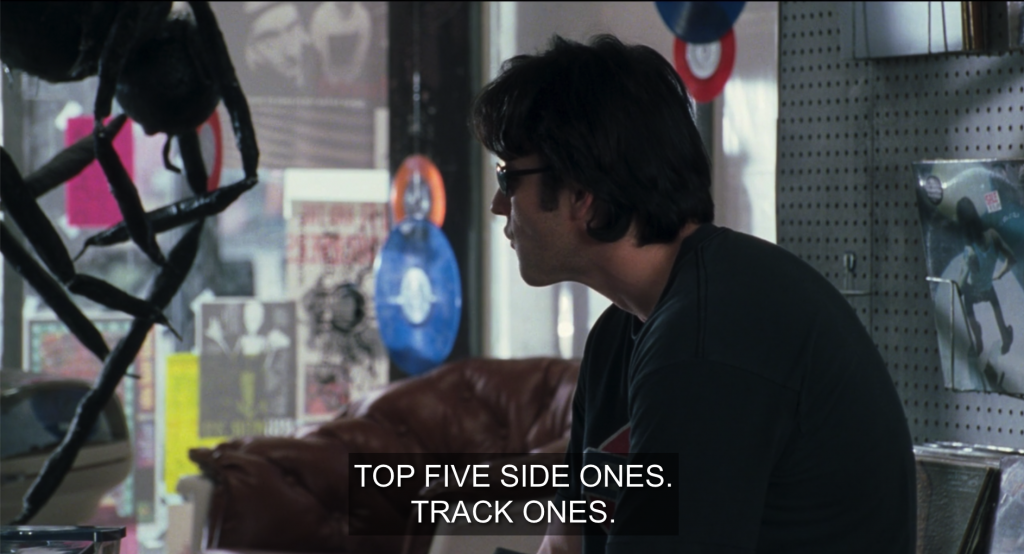

It would not be an exaggeration to say that I grew up with High Fidelity. My way into this multimedia property, which grew out of Nick Hornby’s 1995 novel about a London record store owner’s romantic and professional ennui, was through Stephen Frears’s 2000 cinematic adaptation. Reset in Chicago as a vehicle for John Cusack, the film generated modest box office for distributor Buena Vista. However, as a story about people fashioning their identities out of their obsessions with pop ephemera, High Fidelity’s cultural endurance hinged on its replay value. Shortly after its theatrical run, Comedy Central acquired the broadcast rights and Buena Vista released the film on DVD and VHS (Dempsey 2000).

I encountered High Fidelity at my local Blockbuster at the beginning of my senior year of high school. By 17, I could credibly call myself a music fan. I cobbled together a respectable CD collection acquired through afterschool odd jobs, gifts, and mail-order subscriptions. I archived back issues of Rolling Stone. I wore out the spine of the SPIN Alternative Record Guide that I got for my thirteenth birthday. I logged countless hours watching VH1, streaming Rice University’s radio station on RealAudio, and futzing around with Napster. But my best friend recommended High Fidelity to me. She was a Hornby fan and thought I’d relate to a protagonist who filters human interaction through pop music. In truth, I had not experienced heartbreak or career dissatisfaction. I also heeded other people’s lists instead of making my own. But I felt at home in Frears’s Championship Vinyl, which had Depeche Mode’s 12” “Condemnation” single mounted by the entrance. I wanted to get lost in the stacks, forever discovering my new favorite band while refiling inventory.

The following summer, I packed a paperback copy of High Fidelity to take to freshmen orientation at UT-Austin. By sophomore year, I hosted a show on KVRX. I lived out my Championship Vinyl fantasy through college radio. I engaged in music criticism in album reviews, at house parties, and between gigs. I also made a life with the station’s music director, who also saw this movie and hoped to find a love as powerful as the kind Stevie Wonder describes in “I Believe (When I Fall in Love with You It Will Be Forever)” over the film’s end credits. But it was also through this experience that I recognized how toxic masculinity took root in certain strains of music fandom. I learned that I could listen to Björk and Britney Spears. I made peace with disliking the Smiths and Creedence Clearwater Revival. I stood up for Kate Bush and Sade in casual conversation and while rereading High Fidelity. I became more sympathetic to Laura, the maturing ex-girlfriend of High Fidelity’s manchild protagonist Rob, whom one male deejay called a bitch. And like many female deejays at the station, I weathered harassment from predatory male listeners. I nurtured a nascent feminism to avoid soil erosion. I began reviewing and programming more music by women. I also screwed up the courage to ingratiate myself with the host of the station’s grrrl-punk show, who also helped establish the University’s feminist sorority and coordinated Ladyfest Texas 2003.

As a new member of Alliance for a Feminist Option, I befriended a group of women keen on making their own noise. Or noise(s), as AFO was a feminist coalition peopled by students with different racial and ethnic backgrounds, gender identities, sexual orientations, sizes, and abilities. Respecting the group’s diversity and consensus politics required me to check my privileges and assumptions as a cisgender white girl. I tried to listen more than speak and help the group execute logistical details for programming and promoting demonstrations, art auctions, and vegan café fundraisers. I was intimidated and had a lot to learn. They seemed more assured in their feminism. They cited books I hadn’t read. But I always felt in my element at the makeshift dance parties that followed our Monday night meetings. In the thrall of collective possibility, I stomped and shimmied to M.I.A., Peaches, Ladytron, the Gossip, and Le Tigre. I unclenched and rode the beat, knowing I would not have to defend the pleasure this music gave me to the coolest grrrls on campus. Under their influence, I took up blogging and eventually became a scholar of female musicians’ creative labor. I also saw myself and my friends in characters like High Fidelity’s Laura, an accomplished professional who wants to build a life with someone who isn’t afraid to commit to a future with her. As I replayed High Fidelity throughout my twenties, I’d graft our ambitions and desires onto Laura’s underwritten life.

Side B: Intervening Upon the Past

Weeks before High Fidelity’s Valentine’s Day 2020 release date on Hulu, a few friends asked if I planned to watch the Zoë Kravitz-led remake. I had kept up with the project’s intermittent trade coverage over the past few years. I thought it was clever to cast the daughter of Lisa Bonet, who played one of Rob’s love interests in the film, as the lead. I was interested in the project and flattered to be considered an authority on the subject, but I had two misgivings.

First, I was frustrated that the show was set in Brooklyn. As someone who has lived my adult life in college towns, the bulk of my music library comes from independent record stores in mid-size cities. As a TV viewer who enjoys sitcoms about listless adults, I wish more of these stories were set anywhere but New York or Los Angeles. Building a show around a record store could give television professionals a chance to build storyworlds for underseen communities like Birmingham or Columbus and mine drama out of a neighborhood’s character conflicts. Second, I was intrigued by High Fidelity’s race- and gender-flipped treatment, which promised to correct the source material’s entrenched white heteromasculinity by representing female record store clerks as knowledgeable fans and intermediaries. Some of my best experiences and most cherished finds have been at female-owned record stores. Angie Roloff at Madison’s Strictly Discs supplied me with all of LaBelle’s studio output. Brittany Benton of Brittany’s Record Shop in Cleveland sold me Cherrelle’s High Priority. I bought Patrice Rushen’s Pizazz at Square Records! in Akron, co-owned by Juniper Sage. I’ve also known a number of female record store employees, many of whom have negotiated sexism on the floor. For example, a former student recently spoke to my undergraduate gender and pop music seminar about her experiences working at the local record store and reflected on deciding not to supply the store with records by predatory male artists and educating the staff about how to advocate for female employees when they are overlooked by male customers. I wasn’t sure how or if High Fidelity could address these issues, but I was cautiously optimistic.

On first watch, High Fidelity reminded me of another cultural touchstone from the early 2000s: Sex and the City. In the book and in the film, Rob is the kind of guy Carrie Bradshaw would date for an episode before he made fun of her for owning a copy of Madonna’s The Immaculate Collection. At the beginning of season six, Carrie dates a Rob-like fiction writer who dumps her on a Post-it and probably cracked his next novel after ranking his ex-girlfriends. Kravitz transformed Rob into Carrie by channeling Sarah Jessica Parker’s cool-girl effervescence and romantic neurosis. However, I began to bristle at some colleagues’ enthusiastic response to Rob as a “complex female character” and an emblem of girl-boss feminism. It was fun to watch a biracial queer Black woman extol the virtues of Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk, dress down a middle-aged white man with superficial knowledge of Wings’ live catalogue, and explain the significance of finding an original UK pressing of David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World. It was also great to hear the show’s soundtrack respond to the book and film’s fetishization of British punk and American soul by putting Black popular musicians like Marvin Gaye in dialogue with their peers and successors. And it was great to see the property’s gradual acknowledgement that women of color exist in music communities. The book lacked any female characters of color while the movie included an unnamed Asian patron and cast Lisa Bonet to play a part originally written as a white woman. But, as with Carrie, I grew impatient with Rob’s narcissism eclipsing her friendships. I also had so many questions about Rob’s Blackness that the show was unequipped to answer. How does she relate to her white mother? Where is her Black father? Did she grow up in Crown Heights, where the show is set? How much does it cost for her to live and work there? Why does she primarily date white people? How does she feel about her Black ex-fiancé dating a white woman?

I also became more interested in Cherise, a Championship Vinyl employee played by Da’Vine Joy Randolph. Cherise is based on Barry, a character whose boorishness repelled me on the page and in the movie. But Randolph imbues her interpretation of Championship Vinyl’s resident blowhard with moral conviction and creative restlessness. While Barry trolled for fights about good taste as a contrarian white man, Cherise insisted upon an ethics of care as an aspirant musician who knows that Black female artists’ innovations are often stolen and effaced. Furthermore, Randolph gave depth and vulnerability to a character sidelined by Rob’s journey. After finishing the season, I had a more pressing question: how does Cherise challenge Rob’s relationship to Blackness as a thick, dark-skinned employee with ambitions beyond the store?

The show’s inability to fully address these questions speaks to its optics-based approach to diversity that Kristen Warner might describe as “plastic” (2017). [Please also see NRFTS’s featured discussion with Warner and James Rendell, “The Politics of Casting and Media Fandom.”] It is fitting to cite Warner here, as she is one of contemporary media studies’ most thoughtful and rigorous scholars of television and film’s representational strategies. She also inspired me to write this article after helping me process the show’s shortcomings. The catalyst for this article came from a conversation we had about Cherise’s entrance in the pilot and my incredulity that a Black female New Yorker in her late 20s would embrace Dexy’s Midnight Runners’ “C’mon Eileen” as a bop. We brainstormed other music cues that Cherise could deploy to challenge her colleagues’ studied eclecticism, like Evelyn “Champagne” King’s “Love Come Down.” If Rob’s brother loved Luther Vandross, why did Cherise have to adhere to her doppelgänger’s new wave allegiances? As I did with Laura, I speculated about Cherise’s life offscreen. Did she grow up in Crown Heights? Where does she live? Does she have roommates? How long has she worked at Championship Vinyl? How long has she wanted to make her own music? When does she write songs? Why does her last scene in the series, when she teaches herself how to play Wonder’s “I Believe (When I Fall in Love With You It Will Be Forever)” on guitar, remind me of Aretha Franklin searching to find her voice in Dinah Washington’s repertoire years before she covered “Respect”?

I began pursuing these questions in March 2020. My university had closed campus to minimize the spread of COVID-19. I decided to lean on my training instead of stare at the walls. I dug into the text(s). Over our two-week break, I re-watched the series and the film. I drafted plot segmentations and clipped every scene and music cue that the TV show shared with the film. Then, I cross-referenced the two screen adaptations with the book. My hypothesis: the cover song is a useful interpretative framework for analyzing screen adaptations.

As a popular music scholar with a media studies background, I often use musical analogies to help grasp and enact non-musical activities. Drafting a book’s acknowledgements section is like writing liner notes. Prepping a lecture is to soundcheck as giving a lecture is to gig. As I watched Hulu’s High Fidelity, I documented each repurposed music cue between soundtracks and recognized dialogue that was either lifted verbatim from the source material and either rephrased by the actor or modified by the screenwriter to account for race- and gender-based character differences. Such alterations reminded me of how a singer can change the meaning of a song by putting emphasis on a word or changing the pronouns of who they are addressing. I also thought about covers’ motific function in High Fidelity, a story about how white male record store clerks move the goal posts around cultural authenticity to avoid growing up. Early on in the novel and film, Barry disagrees with his colleague Dick about Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels’ garage-rock cover of “Little Latin Lupe Lu.” He prefers the Righteous Brothers’ original version. But by the end of the story, he is fronting a retro soul cover band.

While navigating this network of intertextual references between adaptations, I thought about how cover songs function as both artifacts of oral culture and proprietary goods regulated by copyright law. In particular, I thought about how soul musicians’ covers of rock songs during the late 60s and 70s served to confront white musicians’ and executives’ plunder of the blues and other Black musical innovations by reclaiming rock ‘n’ roll as their own invention. Emily Lordi identifies soul covers as expressions of Black musicians’ efforts to “parlay cultural displacement into a claim to multiple musical traditions” (2020, 47). Does soul logic apply to Black actresses, who often have to find humanity in small parts and stereotypes? In my article, I sought to demonstrate how Cherise and Randolph used their supporting status to “transfor[m] expressive deprivation into abundance” (Lordi 2020, 46). Randolph found Cherise by filtering the words of white authors—Hornby, actor Jack Black, the film’s team of white male screenwriters, and TV showrunners Sarah Kucerska and Veronica West—through her own lexicon. She invented a Black female music nerd in the absence of a robust canon from commercial television and film. She also had to interpret a brute, Will Straw’s blowhard archetype for masculine music connoisseurship, while trying to avoid becoming a mammy (2002).

I had not read Liner Notes for the Revolution, Daphne Brooks’s recent tome to Black women’s musical genius, until after I revised my article for publication. However, I recognize its structure and stakes in what I endeavored to demonstrate about Cherise. Brooks uses the record as an organizing principle by sequencing her book’s case studies across two sides. Side A focuses on Black women’s “intellectual labor” as critics and historians while Side B exhumes “elusive Black women musicians” through engaging in speculative interpretation as a tactic to work around the archival negligence of artists like obscure blues women Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas (2021, 45). Similarly, this article first examines Cherise’s critical faculties as a record store employee who challenges her boss’s biases and privileges and then posits what kind of music she intends to make based on limited narrative details and Randolph’s conjecture. Brooks’ and Lordi’s recent books are part of a bright constellation of revisionist histories from scholars like Jayna Brown, Maureen Mahon, Regina Bradley, Amber Musser, and Kimberly Mack who rightfully recenter popular music studies around Black women’s artistry and listening practices. Many of these scholars also contributed work for NPR Music’s 8 Women Who Invented American Popular Music, a multimedia project about the foremothers of jazz, country, blues, and salsa. This was part of the outlet’s ongoing Turning the Tables series, which Ann Powers and Jill Sternheimer launched in 2017 to recognize women’s musical accomplishments and skills by drawing upon female-identified journalists, artists, and scholars’ critical acumen.

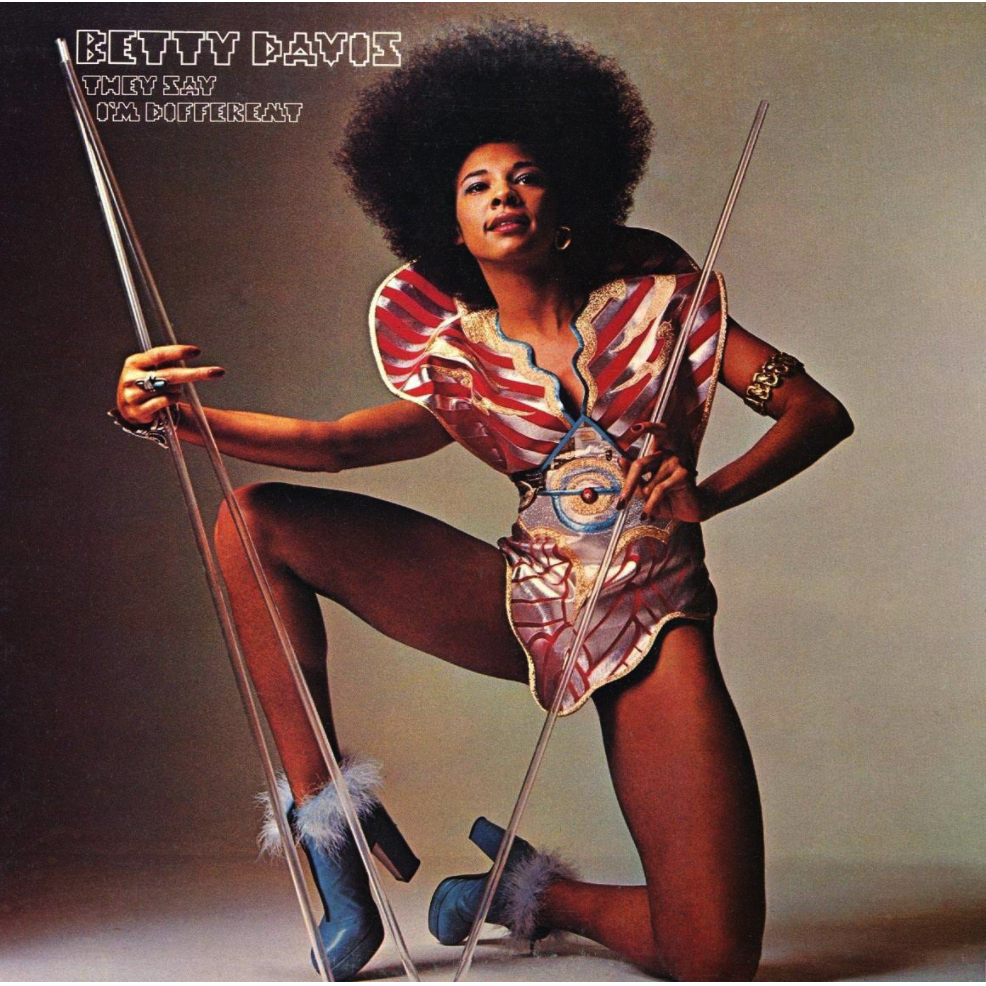

As someone who grew into adulthood as rock masculinity set the cultural agenda and Pitchfork employed more men named “Mark” than women, I am happy to have lived long enough for it to be possible to reinterpret High Fidelity’s toxic masculinity through Black women’s musical expertise. However, I also know how easy it is for the Cherises of the world to be lost to time. In the fourth episode, Cherise puts up a flyer at the store to start a band and is promptly rejected by a male patron. Betty Davis’s “They Say I’m Different” plays in the background during the scene. Davis, a funk pioneer who wrote and produced a singular run of albums in the early to mid-1970s, retreated into obscurity while her ex-husband and lovers’ legacies endured. She was rediscovered in the 2010s after Light in the Attic Records reissued her catalogue and a documentary was made about her career. Popular music scholars have been at the forefront of her reappraisal. Sociologist Oliver Wang contributed liner notes for the reissues and Mahon devoted an entire chapter of her book, Black Diamond Queens: African American Women and Rock and Roll, to her short but significant career. But for every Betty Davis who has to wait 30 years for the culture to catch up with her, there are hundreds of Cherises who never find an audience.

But the Cherises of the world are also beholden to the vagaries of television programming and distribution. Media scholars like Warner, Racquel Gates, Al Martin, Brandy Monk-Payton and Aymar Jean Christian have demonstrated how Black representations in commercial television and film contend with industrial structures undergirded by whiteness. It was for these reasons that I was unsurprised by High Fidelity’s cancellation and worry that it might be lost in Hulu’s library as media conglomerates absorb each other and streaming libraries restrict access through opaque licensing practices. It is within these economic and legal realities that covers and soul logic risk ossification into intellectual property. While Aretha Franklin was not relegated to the B-plot of “Respect,” the royalties generated from the song’s radio airplay went to its songwriter, Otis Redding (Sisario 2018). Similarly, pop songs and cancelled TV shows can fade out and replay indefinitely, or for as long as fans can access them before they strain to remember what they lost.

Read Alyxandra Vesey’s article ‘Have you got any soul?’: reinterpreting High Fidelity’s relationship to Black cultural production in New Review of Film and Television Studies.

References

Daphne A. Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021).

John Dempsey, “Comedy Net Gets ‘High,’ Other Laffers,” Variety vol. 268, no. 29 (July 17, 2000): 3.

Emily J. Lordi, The Meaning of Soul: Black Music and Resilience Since the 1960s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020).

Ben Sisario, “How Aretha Franklin’s ‘Respect’ Became a Battle Cry for Musicians Seeking Royalties,” New York Times, August 17, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/17/arts/ aretha-franklin-respect-copyright.html.

Will Straw, “Sizing Up Record Collections: Gender and Connoisseurship in Rock Music Culture,” in Sheila Whiteley (ed.) Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender (New York: Routledge, 1997), 3-16.

Kristen J. Warner, “In the Time of Plastic Representation,” Film Quarterly vol. 71, no. 2 (2017): 32-37.