By Alex Svensson

The Blair Witch Project has officially turned 25. Released theatrically on July 30, 1999 (with a rapid home video release around Halloween of that same year), Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez’s found footage horror phenomenon about three missing college student documentarians on the search for the titular evil in the vast Black Hills woods near Burkittsville, Maryland was an instant success. The scrappy, improvisational indie chiller received heaps of critical praise, stoked public fascination, and garnered high box office earnings amidst the backdrop of Y2K paranoia almost three decades ago, cementing its place in the canon of horror history. The film has been applauded, studied, and imitated over the years for its raw, realistic approach to the horrific and its deceptively simple experimentation with film and video technologies. But much of the success has also been attributed to the creepily clever promotional paratexts, concocted by Myrick and Sanchez in tandem with producers and marketers from Haxan Films and Artisan Entertainment.

Commemorating the 25th anniversary of the film for People online, Maddie Garfinkle delivers a familiar refrain, asserting that the “marketing campaign for The Blair Witch Project was crucial in convincing audiences that the film was based on real events. […] To maintain the illusion of authenticity, the actors were not permitted to do press for the film before its release, per Collider. Furthermore, their profiles on IMDb were marked as ‘deceased,’ adding another layer of realism to the narrative. […] By the time the truth emerged, some viewers were already convinced that the actors were genuinely missing, and the Blair Witch myth was real.” The haunting and enigmatic official website for The Blair Witch Project has been particularly noted for furthering this terrifying breakdown between reality and artifice – fostered in part through the presence of photographic and textual documentation of recovered artifacts purported to belong to the young missing filmmakers (A/V equipment, rusty and damaged 16mm film cans and Hi8 tapes, a stained and tattered journal, an unsettlingly abandoned car, newly unearthed documentary footage not found in the feature film, and so on).

Though I have a deep, long-standing affection for the vast textual word of The Blair Witch Project as both horror fan and scholar (I teach the film and its marketing in my found footage and American horror cinema courses, where it is often a class favorite amongst students that weren’t even born when the film hit theaters), I find that discussions of the film’s paratextual legacy can typically be mired in hyperbole and rote regurgitation of key talking points. For example, see Claudia Picado’s recent piece for Collider, where she breathlessly and at times a-historically claims that Blair and its website “revived the found footage sub-genre,” “invented viral movie marketing,” and “could not be replicated today.” Similarly, Josh Rottenberg details in a 25th anniversary piece for the Los Angeles Times online how The Blair Witch Project “revolutionized movie marketing,” and in doing so considers the historical and technological context of the film’s eerie, evocative web presence:

In the 1990s, the explosive growth of the internet promised to supercharge this engine into a high-speed, global force, extending the reach of movie marketing campaigns into uncharted corners of what was still being quaintly called “cyberspace.” But at a time when the concept of virality was still confined to infectious diseases, it took a low-budget, under-the-radar horror movie called “The Blair Witch Project” to wake up the industry to this new tool’s full revolutionary potential.

Yet was Blair’s marketing so immediately and undeniably impactful in this industry-shattering way? What are the consequences of thinking about it in such a totalizing manner? While many are eager to comment on the radical or extraordinary aspects of horror’s entanglements with and exploitations of the World Wide Web in the context of Blair, I am more so interested in using the occasion of this anniversary to sketch out some brief thoughts on the everydayness and ubiquity of horror as it was experienced on personal computers in the early days of the Internet. We need to consider more closely the basic, replicable web design, popcorn movie aesthetics, junk culture ephemerality, and at times silly, carnivalesque frights of official horror websites – even those that might not have the same unsettling and enigmatic transmedia ambitions as Blair; these qualities of such web-based paratexts all matter just as much in shaping the experience, identity, and memory of the horror genre.

In his recent book Hollywood Online: Internet Movie Marketing Before and After The Blair Witch Project (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024), Ian London speaks to and complicates such claims about the outsized influence of Haxan and Artisan’s online marketing prowess – all without diminishing the already-evident commercial and cultural importance of Blair and its marketing. Importantly, London notes that one crucial assumption worth challenging is that the film’s website “spawned a cycle of imitations based on the model it provided” (116); as he goes on to argue:

There is actually little evidence to support this. In fact, the number of films whose online promotions shared key commonalities with Blair’s campaign is very small. […] Blair did not, contrary to standard narratives, inspire a wave of identical online promotions. Because the Hollywood majors saw no reason to invest in such a volatile and risky promotional campaign, one that could easily turn negative, they continued to use the new medium safely and conservatively as an extension of traditional media (116, 122).

Thinking of such “traditional media” allows us to consider a range of web-based paratexts: from glitchy, slow-loading QuickTime or Shockwave trailers, downloadable desktop wallpapers and screensavers, and emailable virtual postcards, to fan-centric discussion forums and chat rooms, rote computer games, and a wide array of online contests, “horror” on the net was not just marked by or experienced through dread, terror, shock, or aesthetic rawness. Instead, these sites (or, at the very least, their rough-hewn digital fragments as salvaged and experienced through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine) remind us that horror has always had the potential to be humorous, pleasurable, gimmicky, glossy, schlocky, and – importantly – even mundane. I find this is neatly illustrated in the image below, taken from the Halloween: H2O (Steve Miner, 1998) official site: seductive, spooky imagery snuggled up next to generic, hyper-promotional ad copy and links to home video purchases. While easy to look at as crude and obvious in both their design and commercial intentions, webpages like the one for H20 nonetheless function as gateways towards further experiences with the horror genre – the iconography of series monster The Shape on apparel and VHS cover art, the visage of protagonist Laurie Strode tiling the family computer desktop, even the snippets of slasher imagery in the (gasp!) Creed “What’s This Life For?” music video are all – to borrow from Jonathan Gray (2010) – part of the paratextual world that “constructs, lives in, and can affect” the shape, meaning, and experience of any genre, including horror (6).

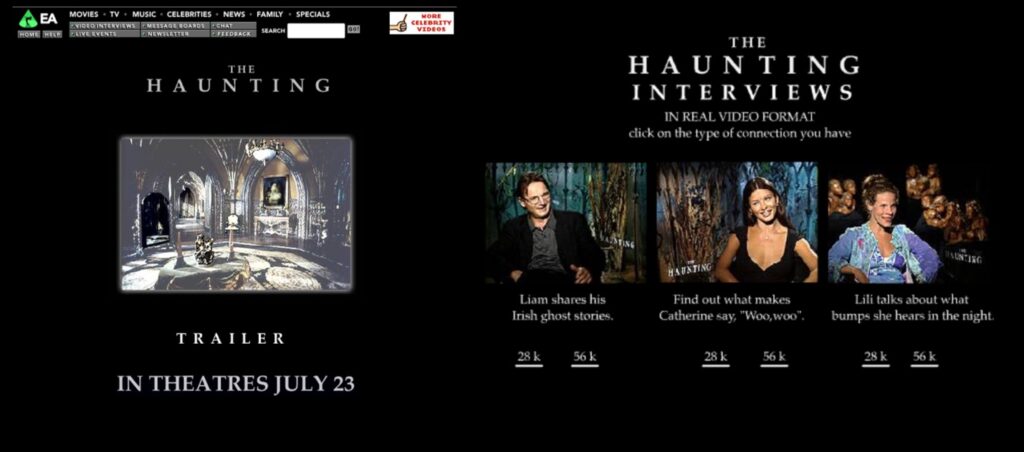

The official website for DreamWorks Pictures’ The Haunting (Jan de Bont, 1999) – a remake of Robert Wise’s 1963 horror classic of the same name – is also emblematic of this approach to the genre and its presence on the web. Entering the site, users are greeted by an image of the movie’s foreboding, haunted manor house, the title of the film floating and pulsating in a ghostly fashion just above. This is all fairly innocuous and quite flat (both visually and affectively), though the accompanying soundtrack elevates the proceedings, playing like a Flash animated riff on the entrance to a dark ride; users are first blasted with a heavy, jarring noise when the link finally loads, followed by a dissonant chorus of what sounds like harsh winds, distant howls, and peculiar, child-like bells and chimes (all slightly crushed, distorted, and made a bit hollow sounding through outdated digital compression).

The image quickly gives way to a still shot of inside the manor, with various highlighted objects throughout the space acting as menu items to click about and navigate toward new pages: a doorway leads to production information and details on the legend of Hill House; a mirror provides cast images and bios; an ominous painting gives way to a writeup on de Bont; and a suspiciously vacant chair links to three video interviews with stars Liam Neeson, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Lili Taylor. These latter press junket videos are interesting, in that they spend time detailing their stars’ thoughts on the afterlife, the existence of ghosts, and the stuff that makes them shudder – things that audiences and users themselves might ponder after they’ve turned the lights out for the night and start to listen to their homes creak, crack, and settle, or the wind outside begin to bellow.

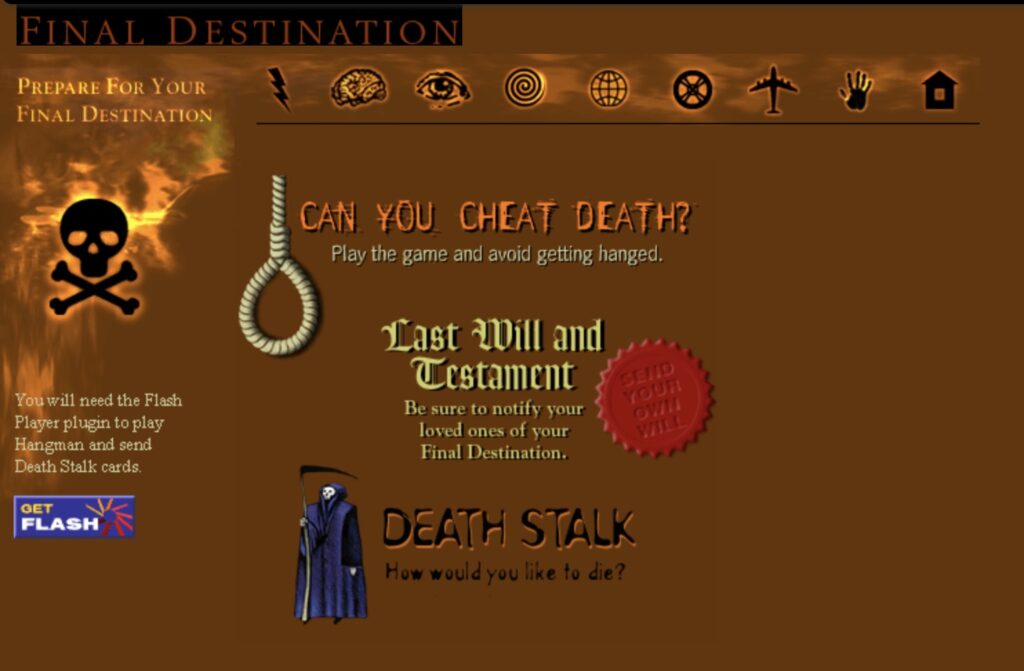

Like with the ghost story-centric interviews found on The Haunting website, other official horror film hubs also took pleasure in pondering the presence of death and the supernatural across everyday life, weaving gruesome discourse and gallows humor into the fabric of banal online browsing. Taking this to particularly inventive and morbidly amusing heights is the site for Final Destination (James Wong, 2000) – cleverly named “deathiscoming.com” – which invites users to not just access the typical press kit copy and promotional clips, stills, and contests, but to navigate through a macabre web of psychic experiments, strange anecdotes of premonitions throughout history, paranormal inquiries, and prompts that encourage site visitors to consider their own mortality. This latter item refers to a link to a so-called “Death Clock” that claims to allow you to “find out when you will die” – a virtual throwback to spooky carnival novelties and fairground hucksterism. Other playful ploys on the Final Destination site include the opportunity to “cheat death” by playing a game of hangman, the ability to fill out and email to yourself and others a “Last Will and Testament,” and the chance to win a flight to Paris (presumably not the doomed one from the start of the film…).

With the carnivalesque impulses and origins of the horror genre firmly in mind, such promotional tactics found across the Final Destination and other horror sites also hark back to the exploitation strategies and gimmick films of genre icons like William Castle – recall the “Death by Fright!” audience life insurance policy of Macabre (1958), theatrical pop-out skeletons (“Emergo”) of House on Haunted Hill (1959), vibrating auditorium seats (“Percepto”) of The Tingler (1959), and ghost-vision glasses (“Illusion-O”) of 13 Ghosts (1960). Murray Leeder (2011) reminds us that the term gimmick film “designates a series of mainly horror and suspense films, beginning in the late 1950s that introduced innovative tricks to attract audiences by addressing them more directly than Hollywood cinema is accustomed to doing. It represents ‘disreputable’ novelty and invention” (775). Such trickery challenges “the diegetic closure that we associate with the classical Hollywood style” (777) – the “gimmick film” status marked by cheapness, luridness, Halloween shop hokum, and a knowing self-awareness embraced by promoter and patron alike at the blurred lines between screen and theater.

As noted earlier, The Blair Witch Project and its online marketing have long been praised for such complications to (if not outright erasure of) “diegetic closure,” creating horror out of the inability to tell fact from fiction. Compared to the commercial bombast of other horror sites addressed here, the longstanding and current retrospective discourse around the Blair website often positions it as terrifying, credible, and worthy of continued study due to its interactivity, minimalism, and almost artisanal, experimental nature. Yet we can’t forget that many viewers and users at the time of Blair’s promotion and release were not entirely convinced of the film’s status as real found footage artifact. There is an overreliance on the “everyone believed it was real!” narrative, when in fact much of the pleasure came from recognizing and playfully giving into the artificial authenticity of Blair’s paratextual gimmickry and clearly consumerist imperatives (lest we forget that Blair’s website was entangled with related promotions across a variety of media, from cable TV’s Independent Film Channel [IFC] to video rental behemoth Blockbuster).

In this way, the Blair site is not all that distinct from the under-valued and -studied “gimmick websites” of the late ’90s and early ’00s. Importantly, Leeder reminds us that the “gimmick represents the collapse of advertising and exhibition to an unusual degree” (776). While he is of course thinking about the spaces and practices of theatrical exhibition, his writing on the gimmick here is instructive in framing our thinking about the promotional ploys of early official horror film websites (with the personal computer itself as a site of collapse between exhibition, display, interactivity, and user input). Citing a Motion Picture Herald promotional article from 1959 on Castle’s The Tingler, Leeder demonstrates how the paper was “full of […] suggestions for ‘exploitation and promotion stunts, contests, and merchandising tie-ins, all practicable on the local level’ (26)” – including cross-promotions with various department stores, disc jockey adverts, and even block parties outside of theatrical premieres (or “Screamieres” as Castle called them) (777).

These horror films were not just singular texts contained by the boundary of the silver screen; via the gimmick, the playful thrills and chills of the horror genre spilled out into fleeting moments across everyday life (strolling on city streets; driving; window shopping; scanning through the radio; even the act of walking up to the box office, well before the projector began to roll). I argue that the horror-tinged “gimmick websites” detailed across this blog post were often engaged in the remediation of these earlier innovations and interventions for the domestic spaces of the home and the desktop, offering up old tricks in the form of Flash animations, pop-up windows, mysterious links, and networked interactivity (indeed, look no further than the sites for remakes of Castle’s House on Haunted Hill [William Malone, 1999] and 13 Ghosts [Steve Beck, 2001] to experience the quite explicit online revival and refashioning of such gimmicks).

Like the horror gimmicks of the ’50s and ’60s bleeding out beyond the theater into various aspects of quotidian life, content garnered from horror websites in the ’90s and ’00s was primed to become part of everyday fan practice or to work its way into the rhythms and décor of domesticity. We might think of trailers and interviews replayed like DVD special features or (more currently) YouTube playlists; still images printed out and pinned to bedroom walls (I certainly did this as a young horror fan back at the turn of the century); wallpaper images of Hollywood ghouls and demons acting as backdrops to computer-based school work, chatroom prattling, and banal web-surfing; and horror movie icon screensavers lending a looping, eerie ambience to living rooms, bedrooms, and dens.

Yet the ubiquity of these websites and their content was and always is enmeshed with and complicated by their ephemerality. The ever-looming presence of the trash icon on every desktop acts as a reminder of the potentially disposable nature of such digital paratexts – quickly replaced by the next favorite film, star, or background theme, and always given to the possibilities of file corruption and technological incompatibility as they age. Despite the 25th anniversary fanfare, the original blairwitch.com acts as a reminder of the web’s impermanence and fallibility. The famed site is now difficult to access and navigate in a variety of respects: clicking the actual link now takes users to the Lionsgate homepage (where the film itself is not mentioned, perhaps due to the prospect of a Blumhouse reboot, or to recent controversy stemming from the original cast’s rightful demand for back residuals), while archived versions via the Wayback Machine are frequently doomed to missing images, dead links, and site intro animations that endlessly refresh, inhibiting entry to the main site. If this is the fate of one of the most storied and critically analyzed websites in both horror and Internet history, it is unfortunately easy to imagine the digital rot and obsolescence faced by gimmick websites of seemingly lesser stature. Yet these sites are valuable not in spite of their gimmickry, but because of it, functioning as specific records of horror history, audience experience, and life lived on the early web; they are worth not just pondering and commenting on in the ways Blair Witch surely will be for many more anniversaries to come, but restoring, preserving, and making accessible to future generations of horror scholars and fans alike.

Stay tuned for issue 22.3 of New Review of Film and Television Studies, “Transnational Horror Media Now,” which will be guest edited by Max Bledstein.

References

Garfinkle, Maddie. “How Much of The Blair Witch Project Was Real? The True Story of the Groundbreaking Horror Film, 25 Years Later.” People, July 30, 2024, https://people.com/true-story-behind-the-blair-witch-project-8685471

Gray, Jonathan. Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (New York: New York University Press, 2010).

Leeder, Murray. “Collective Screams: William Castle and the Gimmick Film.” The Journal of Popular Culture 44, no. 4 (2011): 773-795.

London, Ian. Hollywood Online: Internet Movie Marketing Before and After The Blair Witch Project (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2024).

Picado, Claudia. “One of the Most Successful Horror Movies Ever Made Could Never Be Made Today.” Collider, July 30, 2024, https://collider.com/blair-witch-project-marketing/

Rottenberg, Josh. “How ‘The Blair Witch Project’ Revolutionized Movie Marketing.” Los Angeles Times, July 30, 2024, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/movies/story/2024-07-30/the-blair-witch-project-marketing-25th-anniversary-1999-project