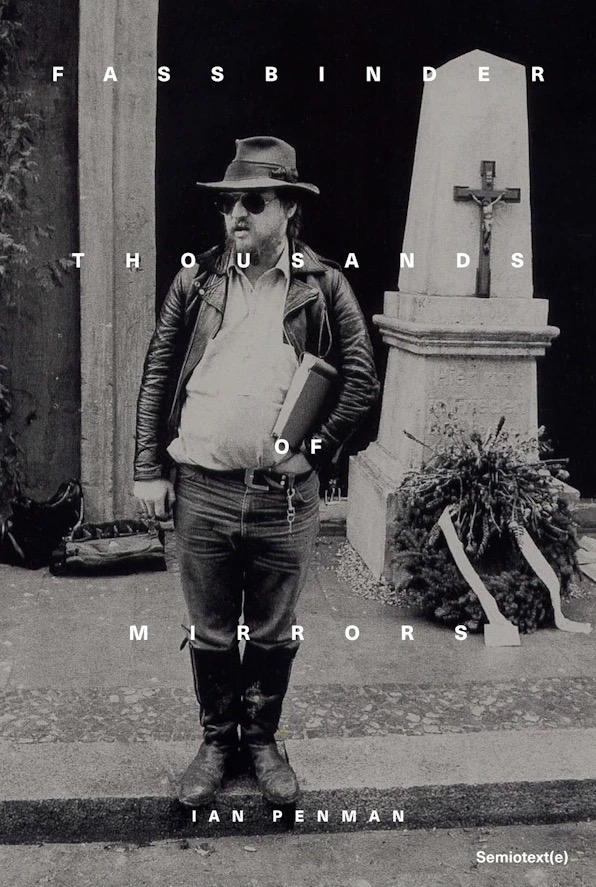

Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors by Ian Penman. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2023, 200 pages, $16.95 (paperback), ISBN 9781635901887

Reviewed by Will Hair

Cult critic Ian Penman’s Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors opens with a refreshingly blunt expression of the author’s intent. With his full-length book on the late German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Penman proclaims, “I have no desire to be some kind of amiable, reasonable, encyclopedic curator of the archive” (13). Eschewing traditions of the average filmmaker biography, Penman instead adapts the most enigmatic traits of his subject. Thousands of Mirrors, like the work of Fassbinder himself, is a hastily written, free-flowing, iconoclastic, and incomplete text. The rich historical context, intellectual rigor, commanding technique, and cultural references will keep even the most knowledgeable of readers on their toes. At once self-indulgent and achingly vulnerable, it’s a work in which the author’s biography is as important as that of the subject. Fassbinder is not a distant, revered figure of recent critical interest for Penman, but a real, flawed, and exceptional individual towards whom he’s been intimately drawn since his youth. This highly subjective approach defines Thousands of Mirrors and makes it a truly idiosyncratic and exciting addition to the canon of books on auteurs.

A long-postponed project that finally began to materialize during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Penman approached his book in the same way Fassbinder approached all his films: “get straight to it and get going right away” (14). As a “monster of productivity,” Fassbinder’s output included more than forty features, miniseries, and television movies before his untimely death at age thirty-seven following an overdose on cocaine and heroin (22). With the filmmaker’s prolific oeuvre as inspiration, Thousands of Mirrors was completed in about four months. The swiftness of its production by no means detracts from the quality. In fact, the result of this approach – a fragmentary structure and a stream-of-consciousness style – is what lends the book a great deal of its unique charm. Foregoing typical chapters and historical linearity, Penman structures his text through numerically marked, journal-style entries that range in length from a few words to about a page. The writing itself effortlessly traverses time and topic at the whim of the author’s wandering mind. One minute, we’re in the middle of a grimy dive bar in late-1970s London, where Penman finds his own cultural awakening amid hard drugs, post-punk groups like PiL (Public Image Ltd.), and the cultural theories of Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno. The next, we’re in post-war Germany with a young Fassbinder, gaining insight into the fractured familial relations that helped shape one of cinema’s most notorious personalities. No matter the setting, Penman’s musings are informed by a lifetime of close cultural attunement and a keen attentiveness to art’s consequential questions of history, politics, and form.

Though Penman, a well-established writer most associated with music criticism, will attract his own devotees to this passion project (his first full-length book), most readers are likely to be cinephiles drawn to the titular man and myth. Thousands of Mirrors is indeed invested in Fassbinder as both “man” and “myth,” devoting as much space to the apocryphal, the speculative, and the unknown aspects of the filmmaker as it does to the historical, political, and social contexts in which he worked. In one especially notable example, Penman cites a story from a previous Fassbinder book, Robert Katz’s Love is Colder than Death (1987). Allegedly, during the final months of his life, the filmmaker took a call from Jane Fonda, who was being considered for the lead in what would’ve been his next film, Rosa L, a project about the Polish-German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg. Fonda started with a cheeky opening: “This is Jane Fonda herself.” The very next day, Fassbinder, evermore the diva, received all of his own calls similarly: “This is Fassbinder himself” (18). True or not, this irresistible anecdote is one of many in Thousands of Mirrors that elucidates Fassbinder’s larger-than-life persona as a product not only of public and critical perception, but of his own self-conscious creation. As Professor Vollmer announces in the opening scene of Fassbinder’s prescient sci-fi tale World on a Wire (1973), “you are nothing more than the image others have made of you.” Fassbinder’s increasing obsession with his projected image is central to the book. More bleakly, it’s what Penman sees as the key contributor to the filmmaker’s demise.

In considering Fassbinder’s trajectory from his early career to his tragic end, Penman offers a useful binary – there’s Fassbinder, the artist, and there’s RWF, the mythic “ogre” and “beast” (21). Penman recognizes the artist as a man of undeniable talents. An autodidact without any formal education, the New German maverick not only wrote and directed all of his films, but acted in many as well. Lush color palettes, austere production design, depressed characters often played by his own friends and family, and claustrophobic interiors are tropes of his expansive filmography. In genres ranging from crime thrillers to science-fiction to westerns, he explored themes of alienation, paranoia, and artistic production. These explorations reflected and critiqued post-war Germany, the Cold War, rapid shifts in technology, leftist ideologies, the rise of capitalism, queer culture, and countercultural trends of the era. These are all essential aspects of the Fassbinder cinematic corpus that Penman discusses and, to some extent, idolizes. Conversely, the author also applies an appropriate degree of ambivalence to his subject. In an early passage, Penman writes that the press “called this monster by his initials as if to temper his outsize reality with a little compression or economy: RWF” (19). In Thousands of Mirrors, RWF is on equal footing with Fassbinder. He even appears on the book’s cover. Mouth agape, potbelly protruding, adorned in a leather jacket and aviator sunglasses with an unkempt beard, and his hand halfway down his pants, this is the form Fassbinder took towards the end of his life. The image, another cynical and searching character, would be right at home in one of his films.

To the age-old question of whether one can separate the art from the artist, Penman, in his own passionate and adroit style, clearly writes in the negative. Fassbinder was a complex figure who embraced sexual indulgence, drug abuse, political provocations, and general obstinate behavior.

Simultaneously, he churned out a slew of arthouse classics that have become increasingly relevant in their bold aesthetics, biting irony, punkish spirit, and irreconcilable approaches to queerness. A figure so complex rejects easy categorization; in treating him with such ambivalence, Penman does both Fassbinder and RWF justice. The filmmaker’s obsession, Penman writes, was self-identity, and his characters, on the same quest, were constantly framed by mirrors. Likewise, Thousands of Mirrors acts as a mirror of sorts for Penman. Part diary, part memoir, part filmmaker biography, the author holds up Fassbinder and his films to reflect on and evaluate his own messy, difficult-to-map life. Though the book is written without didactic intent, if there is a larger lesson to be learned from Thousands of Mirrors, it’s this: mirrors are often much dirtier than we would like them to be.

Will Hair (he/him) is a New York-based writer/programmer and recent graduate of the Cinema Studies Master’s program at New York University. His research interests include experimental and independent cinema, documentary film and video, archival studies, historiography, and contemporary art. He has contributed to Senses of Cinema, Millennium Film Journal, The Velvet Light Trap, and Screen Slate.