The following Q & A was conducted by Editor Maria San Filippo with Andrew J. Owens & Alfred L. Martin, Jr.

NRFTS: Both of your forthcoming books focus on LGBTQ presence in popular culture, in occult media and the Black-cast sitcom respectively. What distinctive affordances for representing queerness did you find in these forms, and what did you find to be their limitations?

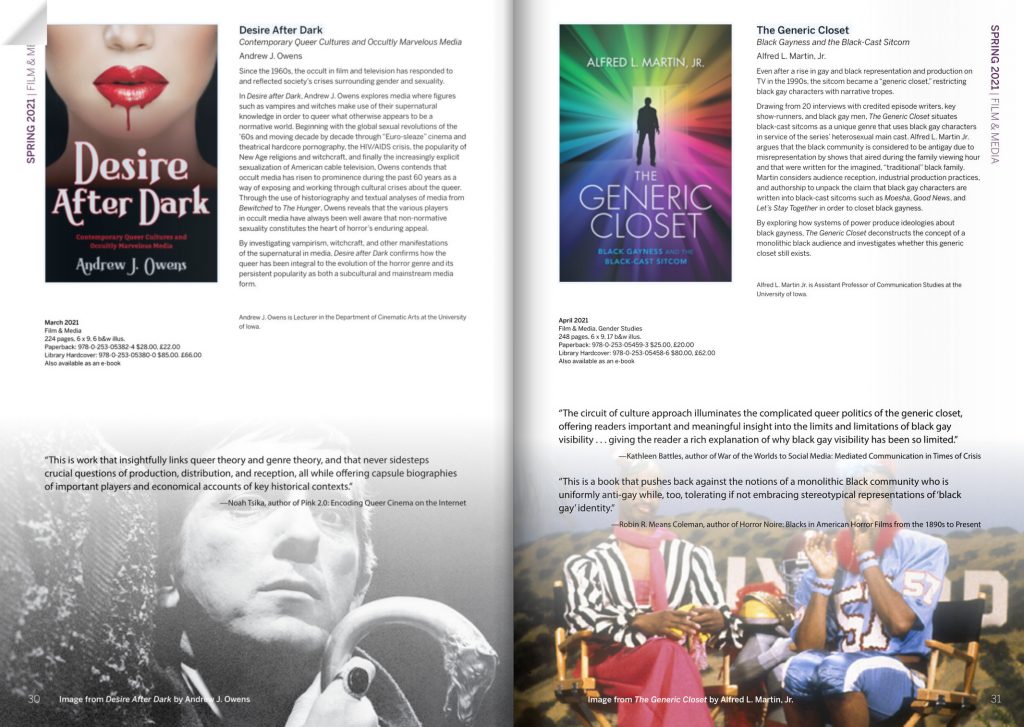

Owens: In many ways, horror/occultism and queerness have always made opportune bedfellows through their associations with “otherness.” The non-normativity that has historically been tethered to what we now recognize as the vast diversity of practices and identities situated as queer has also equally characterized phenomena such as witchcraft and vampirism (e.g., the etymology of faggot traces back to bundles of sticks/twigs often used to burn witches). Even still, representations of queerness vis-à-vis horror can often prove challenging to the positivist political imperatives that continue to haunt so much of queer media and its academic study.

Martin: The Black-cast sitcom afforded a hailing of Black gay identities. Historically, Black gayness first appeared in the Black-cast sitcom in Sanford Arms—a turn to relevance era spinoff of Sanford and Sons. It partly subscribed to the same kinds of representational tropes that were endemic of the era: (Black) gay characters show up and depart from the easy arithmetic that suggests the semiotic linkage between queers and gender inversion, but they do so episodically. When Black gayness returned to Black-cast sitcoms in the so-called “Gay 90s,” it retained its episodic nature, even as white gayness, through white-cast sitcoms like Will & Grace, became central to series—as it had in the late 1970s through Soap. So, if visibility is the aim (and Foucault asks if visibility is a trap anyway) then the Black-cast sitcom makes Black gayness visible. But if we are after something more than visibility, then the Black-cast sitcom exposes its limitations. That is partly an industrial construction in the industry’s (until recently) unwillingness to bifurcate Black audiences along gender, age and class lines. And in so doing, the imagination remains that Black audiences are anti-gay (and to be sure, we saw some anti-gay sentiments emerge around Empire and its inclusion and centering of Jamal’s storylines). At the same time, Black-cast melodramas, like Empire, Being Mary Jane (for a time), and The Haves and the Have Nots imagine Black female audiences and, as such, engage more deeply with Black gay male characters.

NRFTS: How did you each come to your topic, and who/what have been the influential figures and texts for your thinking?

Martin: I initially came to my topic by way of self-awareness and curiosity. I wanted to partly catalog Black gay representation to see where I was on TV (using Cooley’s notion of TV as a looking glass self). But fairly quickly the question became how to study it in a way that didn’t limit my work to the level of the representational. In that way, three works were key to my thinking. First, and perhaps most importantly, was Julie D’Acci’s study of Cagney & Lacey and her (later) assertion that little to no meaning can be found at the level of the text, but that meaning is/can be made about a text in a number of places including in production, in reception, and in the broader machinations of the media industries. Additionally, Ron Becker’s Gay TV and Straight America was instrumental in my thinking through Black gayness as an industrial marketing formation. And lastly (but certainly not least) Herman Gray’s Watching Race because it demonstrates a political economic approach to studying Blackness in television.

Owens: Both horror generally and occultism specifically have been fascinations of mine since childhood, so Desire After Dark really did start and end as a passion project. Along the way, scholars like Harry Benshoff, Richard Dyer, and Ellis Hanson taught me how to look at horror film and television with a critical eye toward both the sexual and gender politics that I sensed, even from a young age, always seemed to be bubbling just below the surface. I’m also particularly glad that I had the opportunity to write about texts that have yet to be given their full scholarly due, such as the work of Jean Rollin and Gerard Damiano’s porno chic smash The Devil in Miss Jones (1973).

NRFTS: How do you combine a sense of how creative practices and industry determinants produce queer cultural products with an interest in audiences’ role in the making/taking of queer meaning from texts?

Owens: As so much of audience and fan studies has taught us, audiences continuously demonstrate the kind of dynamic engagement which never fully allows popular culture artifacts like film and television to be solely impervious monoliths of corporate conglomeration. As such, to borrow from RuPaul, reading practices are fundamental and can never be fully anticipated. Horror is certainly no exception to this rule, as the kind of slash and remix culture generated by series like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and True Blood forcefully bring queerness from subtext (if it was ever subtextual to begin with) to text.

Martin: The first three chapters of my book mostly are about Black queerness and the production of Black queer bodies within industrial contexts. Thus, these first three chapters center Black heterosexuality as a discursive formation. In such a focus, I examine broad industrial discourses that lead particular networks (UPN, TBS and BET) to come to Blackness and/or original programming and how those decisions tend to imagine Black viewers. Those decisions about the imagined Black viewer shape production practices, particularly because Fox, UPN, The WB, TBS and, in some ways, BET, pick up and drop Black audiences and content at will, thus making Black-cast sitcoms, in particular, precarious. It is in the final chapter that I turn specifically to 25 Black gay men to understand how they make meaning of/from television images that are supposed to depict who they are. Thus, with a slightly modified version of the circuit of media study as my guide, I work through industrial machinations, writing and production practices, the ideological uses of the laugh track and Black gay men’s reception.

NRFTS: What were you most surprised to discover in the course of your explorations, and/or what do you think readers are likely to be surprised to learn?

Martin: I was most surprised to find the ways coming out limits thinking about Black gayness in the Black-cast sitcom—or how the Black-cast sitcom uses a generic closet to create a three-act structure for how it will engage with Black gayness. For the Black-cast sitcom, coming out is not a beginning, but an end to these Black gay characters’ life in the televisual universes of the series on which they appear. Writers and producers alike told me they simply could not think of additional stories for Black gay characters (with the exception of the lone Black gay writer for Moesha). The Black gay writer, Demetrius Bady, told me that he had plenty of stories, but that the powers that be at Moesha would always tell him, “We have already done the gay story.”

But when these Black-cast sitcoms were doing the “gay story” there was an incessant focus on “getting it right” to avoid the ire of watchdog groups like GLAAD, demonstrating the ways that organization has, partly, shaped the parameters around which so-called “positive” representations can be developed, written and produced.

Concomitantly, the generic closet gestures toward the different industrial imaginations and parsing of audiences. For the Black-cast sitcom—and I make the distinction between Black-cast comedies, like Blackish and Insecure and broad, Black-cast sitcoms with a laugh track comedy like Moesha or A Different World— there is no segmentation of Blackness in the way Ron Becker details the parsing of liberal, wealthy white viewers that made way for lesbian and gay-focused series like Will & Grace and Ellen DeGeneres’ coming out on Ellen.

So, the lack of sustained visibility within the Black-cast sitcom is twofold: writers need to imagine more ways to tell Black gay stories within the sitcom mode (and perhaps hiring more Black gay writers with some semblance of agency within the writers’ room would open up those opportunities) and the Black-cast sitcom should re-imagine its audience.

Owens: For me, the most surprising part of doing the research for this project was uncovering just how much film and television studios knew about the potential queer resonances of their products, even if there was nothing ostensibly queer on their surface. For example, the ABC screening report for Dark Shadows that I reference in Chapter 1 and that I found in the Dan Curtis Production Records at UCLA absolutely blew my mind!

NRFTS: How do you see your book’s findings connecting with the current landscape of LGBTQ+ and/or racial politics?

Owens: As occult horror continues its popular resurgence, especially on television where it seems as if you can’t throw a stone without hitting a witch and/or vampire, I hope that my book will provide some enlightening historical context for readers/viewers in order to forge connections between the present and the past.

Martin: My book opens with a discussion of the intersection of Obama’s election in 2008 and California’s Proposition 8 and the ways, the logic went, that Black voters and their (allegedly monolithic) homophobia led to both Obama winning California’s 55 electoral college votes and California declaring marriage as an institution reserved for one man and one woman. Despite the presence of numerous white politicians who codify their homophobia into law, somehow Black homophobia (often assumed to come from a monolithic Black church) is more dangerous and more easily activated as a discursive strategy. It’s very easy to see media, particularly sitcoms, as “just” entertainment, however, they are bound within particular discourses. And the discourse about Black folks (monolithically) as anti-gay shapes how programming happens.

NRFTS: Our readers will also be interested to know that you are co-authoring a volume on Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied for the recently relaunched Queer Film Classics series. Why did you choose this film and what will your exploration of it entail?

Martin: Partly, Tongues Untied was selected because it was on the list of texts for which the Queer Film Classics series was looking for folks to write about. But, for me, Tongues Untied is personally important. I have a vivid memory of watching Tongues Untied on a visit to NYC with my parents. As I was flipping channels, I landed on New York’s PBS station after my parents had gone to bed and was absolutely riveted and frightened, particularly by the line “this nut could kill us.” So, partly, I wanted to explore the text because it was one in which a Black gay artist was detailing the lives of Black queers in a way that did not feel exploitative (as some have charged Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning). And given my background as someone who mostly studies television, I thought it might be interesting to explore it as a TV text, not as a cinematic one. And because I also believe that researchers are always present in their work, I wanted to see what would happen with a Black gay man and a white gay man got together to think through the meanings (historical and contemporary) of Tongues Untied.

Owens: Doing a project on Tongues Untied perfectly suits both of our interests in exploring the under-researched intersectionality of queer media, specifically between sexuality and race. The book will combine autoethnography, sustained attention to the documentary’s reception contexts, and its interstitial place between film and television.