Reviewed by Matthew Sorrento

Of all the eras of Hollywood to shape performance styles, Pre-Code remains one of the most fascinating. The looser censorship at the birth of sound offered a flourishing of ideas, even if many actors, especially women, were victim to studio decisions. The era featured urgent acting styles borrowed from the theater, now with the visual attention that the camera could offer. Book-length studies have brought more visibility to these figures: in addition to titles on Joan Blondell and Barbara Stanwyck’s early years, a 2013 biography by Scott O’Brien covers the ignored figure Ruth Chatterton (Frisco Jenny, 1932) who chose to leave the movies in the late 30s, though she worked in aviation and as a novelist and eventually returned to the small screen.

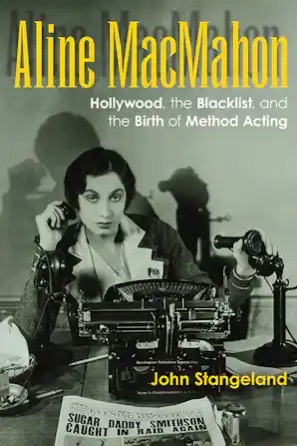

Aline MacMahon was a complex performer, one of the working thespians who flourished on the New York stage before transitioning into the talkies once the innovation of sound on screen was underway. John Stangeland’s thoroughly researched biography addresses the historiographical neglect of this star. Through research conducted using personal archives never before published and other primary materials, the author outlines in a relatively short page count MacMahon’s importance.

In a universe of stars from lowly beginnings, MacMahon, in contrast, had a head start. Born to an intellectual family in western Pennsylvania that soon relocated to Brooklyn, she was the daughter of a stock exchange broker who also published fiction in magazines. Having a complicated relationship with her learned mother, Aline found more inspiration from her aunt, the noted literary figure/social reformer Sophie Irene Loeb, who, like Aline’s father, guided her towards a college degree. Under these auspices, Aline excelled in elocution, recitals, and soon enough, acting. Aline was also part of the wave of women to attend progressive institutions around the passing of the 19th amendment, and she found comfort in Barnard College’s arts programs that helped lead her to the professional stage. Stangeland captures the excitement of the “small”, off-Broadway New York theater scene that gave the more established Broadway a run for its money. MacMahon entered into what reads to the contemporary theatergoer tired of today’s “mainstream” programming like a near idyllic situation. Spotting energy and talent, the professional theater world had its eyes on Aline by the time she was 21.

A contract arrived soon after graduation, along with a suitor ten years her senior, the New York-based city planner Clarence Stein who as her husband would support MacMahon’s acting in pictures on the west coast for part of the year. MacMahon’s timing for comedy made her excel at impersonations, though her gifts for humor resulted in struggles with typecasting. Involvement in the socially-minded Neighborhood Playhouse, after several successful productions, led to an invite to a Moscow theatrical training school in New York, which was as groundbreaking and inspiring as it was taxing, like an outdoor acting bootcamp. As in many discussions of actors on the stage, the reader visualizes how wonderful it would be to see MacMahon in roles once her career takes off, including the 1926 revival of Beyond the Horizon, a play by an author who took special interest in MacMahon, Eugene O’Neill. She began a long commitment to progressive advocacy groups, leading to her graylisting by the studios (while never called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, she did receive a visit from the FBI to her home in New York). And yet, in 1927 she did not stand up against New York laws on indecency in the theater when Maya, in which she starred as the eponymous prostitute, was to be shuttered by city censors. Stangeland discusses MacMahon’s decision as one shaped by Victorian morals, in this case outweighing her modern progressivism.

While MacMahon stood out on the stage, Stangeland cites several instances of her claiming a preference for the movies. With the help of director Mervyn LeRoy, she made her film debut in Five Star Final (1931), in a standout role as the love interest to a tabloid newspaper editor played by Edward G. Robinson. Fittingly, the film was based on a work of the proletarian theater. While offering effective context on MacMahon’s stage works and her other Pre-Code films, like Heroes for Sale (1933), the book would benefit from offering more background information on her screen debut’s source material, a hit stage production by Louis Weitzenkorn, which was beset by its own troubled beginnings.

Stangeland asserts that MacMahon’s Method style contrasted with the “declarative” approaches seen in other performers working in the studio system. While generally true, calling Robinson’s psychological style mainly declarative isn’t accurate, based on his strong moments in Five Star Final and a decade-best performance in Two Seconds (1932), along with standout non-verbal moments in 1940s films noir to come. (Notably, Stangeland discusses MacMahon’s strained relationship with the actor, who pushed his advice on her performance during the making of 1932’s Silver Dollar).

Nonetheless, Stangeland accounts for the performer in focus, offering a means to reassess her work in film. While mostly playing supporting roles at first, she finally got the spotlight in Heat Lightning (1934), the very last film released before the Production Code enforcement, which Stangeland does well at contextualizing. He discusses the film as a key proto noir and one with a strained production, due to director LeRoy experiencing a slump; MacMahon herself noted his “limitations now that I’ve worked with him on a melodrama that should have been a director’s feast” (191). Stangeland does a good job of describing MacMahon as “not the glamour girl or the ice-queen many [men] fantasize about [but] attractive…approachable, intelligent, and down to earth….For many women, she mirrors their own personal struggles and desires” (142). Even if studio offers wouldn’t allow it, she could capture in her roles and fans a range of working class city women as wide as Pallas Athena.

After the Code’s enforcement, MacMahon mainly played nurturing/maternal roles above her age, as in Ah, Wilderness (1935) and The Search (1948). Though Stangeland dissects some key moments onscreen, like one central to her star persona in Heroes for Sale, readers wanting more evidence of her Method approach will have to wait for a book-length study on that topic. At the same time, Stangeland further details how social movements and personal struggles helped shape the artist. In addition to the legacies of the title, MacMahon was one of the first actresses to negotiate her own contract with Warner Brothers, one that allowed for time off to be at home in Manhattan with her husband, even if it meant missing out on productions that studios would not postpone for her. Like so many female stars of classical Hollywood, her talents far outshined the opportunities given to her. Stangeland’s account of the woman in full should encourage more studies and new fans of the one-of-a-kind star.