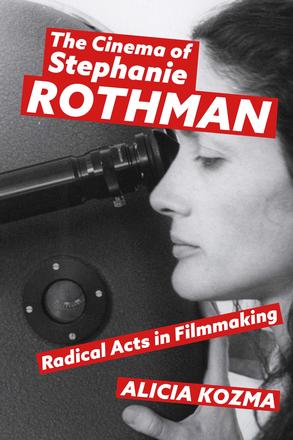

By Maya Montañez Smukler

The following discussion was conducted via Zoom and has been edited for style.

Maya Montañez Smukler (MMS): Thank you so much for talking about your new book on Stephanie Rothman. You introduce a really critical framework, which I can’t wait to use [and which] you’ve articulated so well, which is to rally against the study and discussion of women in production you’ve introduced the “paradigm of exceptional women.”

Let’s start here: The exceptional woman exists, I’m assuming, across all different fields and historical moments. But for our purposes here, what is the exceptional woman in filmmaking, and why has her status been so enduring as a historical approach? And why must be we be aware and cautious of this categorization?

Alicia Kozma (AK): Well, thank you so much, first of all, for reading the book and talking about this. It’s nice to know that someone has seen the thing you’ve put out into the world!

When I say the phrase “paradigm of exceptional women” it’s first useful to qualify what I mean when I say the word “exceptional.” I do not mean exceptional in the adjective sense; I mean as exceptions to the rule. When I think about exceptional women in filmmaking, they stand in as exceptions to the rule of the normative construct of directors as primarily white, cis men.

The exceptional woman essentially functions as a pass for Hollywood as an industry, and sometimes for critics and filmmakers, to mistake the appearance of a handful of women as meritocracy; essentially mistaking tokenism as meritocracy. It’s equally applicable to the gendered labor of directing and film production as a whole, because we could use the same paradigm and apply it to editors and composers, cinematographers, etc.

For me, the paradigm of exceptional women is tokenism disguised as parity. Often, conversations about the disparity of women’s labor behind the camera are met with the same refutations: a list of names of a handful of women directors who are raised over and over again as examples of women in the director’s chair. The response becomes: “Of course women have the same opportunities as men – look at Kathryn Bigelow, Chantal Akerman, [Agnès] Varda, Lois Weber,” and down the line.

Of course, these are women with legendary careers, but their consistent invocation causes two issues. First, it is a very small cadre of women used to stand in for all women behind the camera. Two, it effectively roadblocks continued and nuanced conversation about gendered labor disparity in Hollywood; it can be a conversational standstill. If the argument being made says women are denied equal opportunity in the director’s chair, and the counterpoint is “well, here’s list of women who direct,” it can stop the industry from questioning the status quo when thinking about gender labor parity. Tokenism disguised as parity is particularly difficult for increasing the kind of breath and depth of who gets to tell stories, whose stories are told, and who gets to make the decisions about who gets to tell what.

Tokenism disguised as parity is particularly difficult for increasing the kind of breath and depth of who gets to tell stories, whose stories are told, and who gets to make the decisions about who gets to tell what.

Additionally, when that same small group of women is raised over and over and over again they become both tokenistic and overly represented; they coalesce into a homogeneous block in and of themselves. So, if we look at this kind of very small representation, we really are still looking at white women. We’re primarily looking at cis, hetero women. We’re primarily looking at women either from the United States or from Western Europe.

It is I think, now, especially with Sight and Sound’s new kind of tumultuous overthrow, the canon — quote unquote —

MMS: Such an overthrow, wow!

AK: Naming the person, Chantal Akerman, who 100% could not have cared less about lists at the top of the list with Jeanne Dielman…, now as the number one Sight and Sound’s best movie of all time!

I mean, I joke about it. It is a big deal, and it’s exciting, but it’s also sad that it has taken this long, and that it is this big a deal in 2022.

MMS: Absolutely. And it’s another list. It’s like, I want the list to change, and I don’t ever want to see another list.

AK: Again, it’s so strange, because what seems like it should be a win for the argument of women filmmakers starts to pose the same problem. Akerman is one of those people who is always invoked as an example of the exception to the rule of male directors. And Akerman is one of those people who is usually represented on lists, regardless of her position in those lists. Her films are widely available, you can buy her movies commercially. All those things are fantastic. But again, they become a roadblock for thinking past having another white [Francophone] woman be the face of women’s filmmaking. And that shapes what women behind the camera can or cannot look like in the future.

The paradigm of the exceptional woman is something that I came up with in part, because I was frustrated that every time I would think about, or have conversations with, or read, or think through gender parity behind the camera, I would be met with the same claims, the same names over and over and over again. And it starts to get to a point where that small group, it’s not good enough. They’re all great, and as I say in the book, and, as I will say forever, they are all exceptional in the adjective sense of the word; any woman who is able to get a movie made in Hollywood, much less more than one, is, truly exceptional as a person, as a creator.

MMS: They’re exceptional, just as a filmmaker.

AK: 100%. The films they make are exceptional. Even their bad films are. But they cannot be representative of all women. They are not representatives for all issues or problems or stories or creative practices that we could be seeing if we had a much broader construction of who gets to be behind the camera — a broader conception of who gets to make decisions and what stories they get to tell.

So, first, it was a little bit out of frustration: “Okay, fine. But like what else? Who else is out there?” Because I’ve seen all these movies, and I know all these women and all their films are great, but you can’t tell me there’s not anybody else doing this stuff, and you can’t tell me there aren’t other people that want to be doing this stuff. In some way I started to get a little indignant that these women were being used as a shield for not wanting to do something that you should be doing.

MMS: And it’s such a burden placed on those women.

AK: Absolutely.

MMS: And they get caught in a bind. For those who are able to be here and talk about their experience making films and then for those who aren’t, the historical burden of always having to represent this small group, represent the category of women filmmakers where they don’t get to be just a filmmaker, an artist, a professional and [can] really be just judged on the merits of their work or the experiences of their work.

AK: They always have to be something else. They always have to be something more. They always have to be signifying. They can’t just be themselves, their work, their creativity, their brains. It always has to come to something else. That was the impetus for me look past these women who have essentially accomplished the impossible as shields for not doing what Hollywood should be doing industrially right.

You cannot just point to them and say, “Oh, there’s four people over here, so we’re good. We just can continue doing what we’re doing. We don’t have to worry about it.”

[Women filmmakers] always have to be something else. They always have to be something more. They always have to be signifying. They can’t just be themselves, their work, their creativity, their brains.

I thought, at first, my way out of that was doing what we do: digging into historiography and digging into film histories and finding those people who had already thought about women behind the camera and what it meant for women to be behind the camera and had pulled together that information.

And in a lot of ways what I found was really encouraging. But then I started to see that same essential logic — and I don’t think in any way maliciously — represented earlier. And when I say earlier, I mean like historiographic work on women and film in the eighties, for example, that was saying, “Well, these are the women that we know are working in film, and there might be more, but we don’t really know who they are, so here’s a list of all women filmmakers,” and then it would just be the same list again. That’s okay, but that’s not good enough anymore. I understand why it was like that during that time, but it must be different now. We have better tools; I’m not stuck just researching microfiche in the basement of a library, and thumbing through whatever back catalogs of Variety I can get my hands on.

MMS: And talking about a movie that you just cannot see —

AK: Yes! That I saw once, and I’ll never find again. It’s just not good enough anymore. It’s a privilege — and it’s a responsibility — as film historians now to say that’s not good enough anymore. We must do better. For me, part of that responsibility, and holding myself accountable, was figuring out a way to articulate this, which is what became the bind of exceptional women and how we need to move around it.

As I was researching the book, and digging up everything that I possibly could on Stephanie [Rothman], I was uncovering women who I had never heard of before —

MMS: Oooh, I want to see your list!

AK: They were primarily working in either adult film or second wave exploitation film. But now I have a whole other list, and I can’t promise that I’m going to be able to find as much information, but at least in my head it’s like issuing a challenge to all the other film historians: “I found these people. I bet you have found names that have popped up. Maybe, if we got together and put these names up on a wall to figure out where to go with them and start building this list out…”

The biggest frustration I have with the idea of these “exceptional women,” is that it’s not just historical, and it’s also not just contemporary, it is the argument that’s used to keep this system ensconced into the future. We build the future based on what we know from the past and based on how we’re operating in the moment. If we can’t move past this now, we are essentially ensuring the future is going to look this way as well.

There is an argument that advocacy groups like the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and others [USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative] use as part of the rationale for that work: If you can’t see it, you can’t be it. This is, of course, absolutely true. But built into that is a follow-up point: if we empower women to pick up cameras and to teach them to tell their stories, then we can change things, and we move forward. Again, that’s not wrong, but it bypasses the fact that women have already picked up cameras. Women have already been telling stories. There’s something else going on that’s throwing up roadblocks. It’s not new for women to direct films, to write films, to be creative, to work in film in a wide variety of professional areas. Women have been picking up cameras and telling stories since the beginning of film. It’s not new.

For me part of that is this idea of tokenism disguised as parity. It’s not as simple, unfortunately, as put a camera in someone’s hand and then they can change the world. It sounds lovely, but they’re entering a system that is set up to ensure that they fail in a variety of ways. Unless we interrogate how the system is both constructing, leveraging, and exploiting their labor, we’re sending people into the same closed-circuit problem, and it’s not actually achieving the change that we are actively working to see.

MMS: This is a good segue to then talk about history. But before we talk about Stephanie Rothman as a historical subject, I also want to recognize her as a real person.

AK: She is a real person, alive and well!

MMS: You, of course, I have interviewed her several times, and I want to talk about that experience for you. I think, for us as the historians, the historical subject becomes an object that we’re going to write about, but then also interviewing and talking, and spending time with that real person, which we’ve been lucky to do. And so that film history that we’re working on is also a person’s personal history.

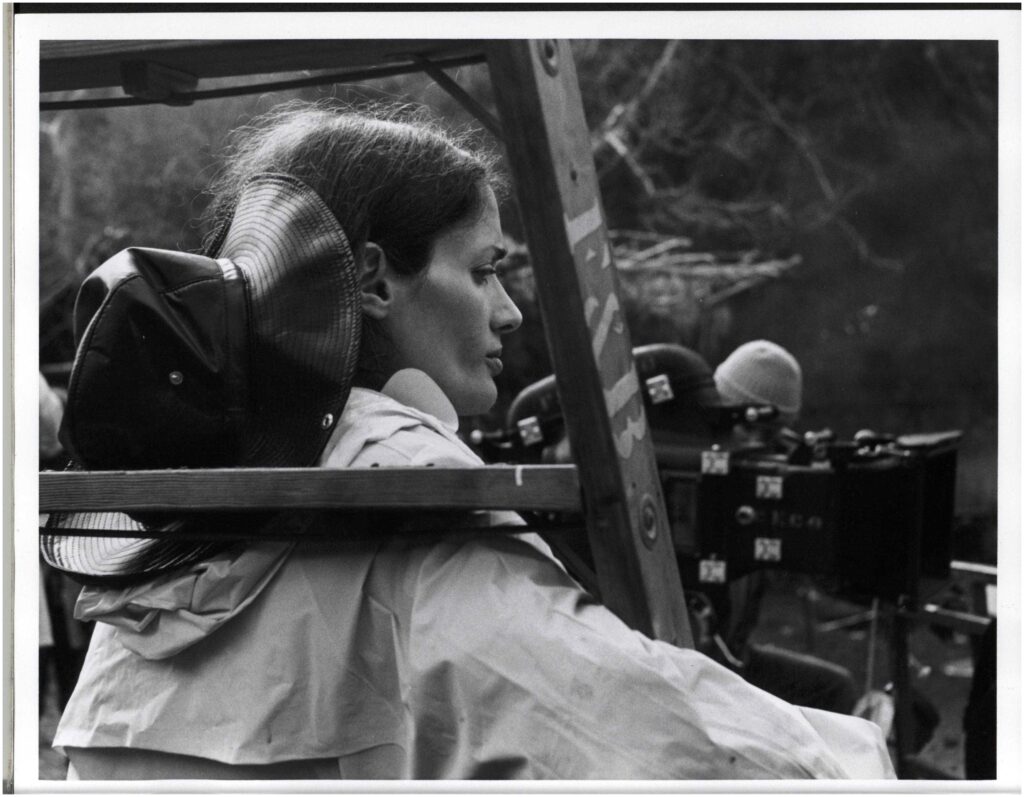

Rothman is such a perfect example, on the one hand, of the 1960s and 1970s New Hollywood filmmaker. Mythology is part of that first generation of “film school brats” who go to film school with the intent to start honing their craft so that they can pursue it in the commercial filmmaking industry, focused on Hollywood. She comes up through Roger Corman, so she’s part of that mythology, and really is a standout example. And, she is also very much a gendered historical subject, one of the very few women filmmakers making commercially oriented films in the 60s and 70s. And in an even smaller pool of women filmmakers working in second wave exploitation films during these years.

What was your approach to situating Rothman within these two historical frameworks? As a filmmaker, not specific to gender as part of that New Hollywood mythology of the 60s and 70s.

AK: That’s a great question, and, I have to say, situating her within the new Hollywood framework was probably the easier of the two, because her films just fit thematically, aesthetically, formally. It’s also interesting, because her career trajectory even fits, as you said, with the myth of the new Hollywood director, writer, multi-hyphenate. It was a lot harder for me to situate her as a woman filmmaker during the time that she was working, and as a woman filmmaker in exploitation because so much of what I knew about women who were making films during that time — and who were as active as Stephanie was and as ideological and as political and creative as Stephanie was — were specifically working in counter cinema.

MMS: Can you give us some of those names of those other women that you’re thinking about?

AK: More of the downtown New York art scene, people like Carolee Schneemann, who’s building from her art practice and specifically working in an explicitly feminist-like counter cinema framework. And Stephanie was not working in counter cinema, and she never wanted to. She said, “No, no, I’m not into that. I want to make mainstream movies in Hollywood just like everybody else gets to do.” And while she was explicitly being feminist, she wasn’t explicitly being political. She never felt particularly connected to the feminist movement that was happening in the 1960s and 1970s, which points to two things: one, she was older than a majority of the people who [were] involved in the movement at the time; and two, she was raised in a way where her whole life had already been lived in what would have then been called a “liberated” way, so it wasn’t new or novel to her.

What was difficult for me, in part, was I had not encountered anybody like that working in that time. There wasn’t really a model for me — maybe Elaine May? Stephanie met Shirley Clarke a couple of times. They had great conversations about the films that they were making and each other’s work, and she was happy for that. But [Stephanie’s] goal was to play in the same sandbox that she saw her male peers playing in, and for her to “make the best work that I can in second wave exploitation and use it as a calling card to jump up into mainstream, Hollywood filmmaking.”

She was older than a majority of the people who [were] involved in the [women’s] movement at the time; and two, she was raised in a way where her whole life had already been lived in what would have then been called a “liberated” way, so it wasn’t new or novel to her.

MMS: I’m thinking of comparable woman filmmaker during this time — what do you think about Joan Micklin Silver? She was an independent filmmaker in art house cinema during that time, and then segues into bigger budget, studio films for her. Such different filmmakers, but also similar in that they made personal films.

AK: I think probably she’s probably one of the closest comparisons for sure. I think Stephanie would have been thrilled to have a start in art house cinema and move into mainstream filmmaking versus fighting to get from exploitation into the art house. Eventually she did this, but it was long after she had left filmmaking – [it’s] today that her films play in art houses. She has talked about this before, saying, essentially, “If my films just played in an art house instead of a drive-in, I would have had a very different career.”

MMS: It’s incredible, there are a few examples of women in the 1960s and 1970s making art house, indie films, but many couldn’t build a body of work because of all these obstacles.

AK: The first conversation I had with Stephanie, I asked her “You know you hit so many roadblocks. Did you ever just want to branch out and just do it all yourself? You were writing the movies. [Her husband] Charles [Swartz] was producing them. You were directing. Did you ever think about just up and doing it all yourself?” She said: “No. All I asked for was access to the same apparatus that everybody else had, and I don’t think that’s asking for too much.”

MMS: It’s not like she’s asking for the biggest budget, either, because she already knows how to make a movie for literally nothing. She’s not getting paid anything!

AK: For women-identified folks who are making films, or even engaging in the historiography, or in academia, there’s so many times where it’s like, “It doesn’t seem like they’re gonna let me in this way. So let me make my own path around the side, I’ll get in through the back door, and I’ll eventually end up where I want it to be.” It’s become almost like second nature in some ways. Stephanie just didn’t want to do it. She did not think she should have to. This is not in the book, but one of the first things she said to me, the first time I met her: “I’m a snob. I’ve already proved my credentials. I’ve already proved my ability. I should be considered exactly the same as anybody else.” And she’s right!

So, situating her as a woman making films was a lot different than situating her as within New Hollywood. Situating her as a woman making exploitation films was tricky at first but in a really good way. Of course, her films are not the first exploitation films that I had ever seen; you get into a habit when you sit down to watch an exploitation film that ends up, essentially, being like a recuperative process. Like “all right, there’s a lot of horrible things happening. Where is the interesting stuff that’s happening, or are all of these horrible things interesting because they are representative of x, y, or z?” You’re digging to uncover the gems that are in these films, and without fail there’s always something interesting to talk about, which is great! But after watching dozens of exploitation films, that recuperative viewing position became my default viewing position. This was tricky the first time I sat down and watched one of Stephanie’s movies, because I didn’t have to do any of that! It’s all right there. That was a different way of watching for me. Essentially, I’d fallen into a very bad trap that I had to get myself out of when I was confronted with her films.

I think Stephanie would have been thrilled to have a start in art house cinema and move into mainstream filmmaking versus fighting to get from exploitation into the art house.

MMS: You identify something that you call the “Rothman Rules.” Tell us about them and how you understand Rothman’s approach to working, or negotiating, the industrial, cultural, and artistic expectations during the time that she’s making her films.

AK: The “Rothman Rules” or the “Rothman Guide To Filmmaking” was essentially her capitulation to being able to maintain her ideological and ethical self, and meeting the requirements of the industry that she was working in. She had a lot of flexibility working for [Roger] Corman. I think probably more flexibility than she would have had if she was working somewhere else. And really all he required was nudity, violence, and sex, and if those things were present in the film, he was happy.

What built the foundation of the “Rothman Rules” was her way of incorporating those things, but in ways that weren’t always exploitative towards the women in the films themselves.

MMS: And the men, too. She presents some really unique male characters in these films — and really, of any films in the 1970s!

AK: Absolutely! Especially in Student Nurses, and also in Terminal Island. And even in Group Marriage.

Think about the opening of Student Nurses. It opens with an attempted sexual assault in the hospital on one of the nurses. Her position was, “Well, I knew I had to open the film with nudity, and so I did. It just so happened to be male nudity. And I knew I had to open the film with violence, and I did — that violence just so happened to be the nurse fighting back against her attacker and the nudity is her tranquilizing him in his backside.” They were really creative ways for her to incorporate the requirements of the genre while not compromising herself.

One of the things that she was really insistent on was the impact and the aftereffects of violence. Her position was “If I show violence, then you’re gonna see blood, and you’re gonna see how terrible it is.” She was adamant in avoiding bloodless violence, or violence that did not show its horrific impact.

I think often about Monk at the end of Terminal Island, when he’s blinded, the audience is supposed to be elated. The good group won. You’re supposed to be very happy, and instead, you’re watching the intense pain of this individual who had already been abused by his closest ally, and that’s what the camera is focused on. It really undercuts the violence at the end of that film as celebratory. Even though that violence is revolutionary, Rothman wants you to understand that there is still a real human, tangible impact to that.

She never actually shows a sexual assault in her film, and she said she never would. She will allude to it. She will show the act attempted, and then interrupted. She wanted to make sure that violence was always paired with its aftermath, and its impacts. And importantly, as you said earlier, she wanted to make sure that men were given the same full range of emotions to explore that women were given. One of her pet peeves is that men never scream in films, and they’re never scared. It’s always women. She says, “I’ve seen men scared in real life all the time. Why wouldn’t I also see it on film?”

It really was a way for her to sit with herself because she never wanted to be making exploitation films. It was something she did, because she, at some point after years in the industry and years of doors closing in her face, that if she wanted to be making films, Corman, and then later [Larry] Woolner, were really the only people who are going to give her the opportunity to do it. She said, “All right, if I have to be here and if I have these boundaries for including specific types of content, I’m going to figure out a way to get through so I’m not compromising myself. I’m not compromising my ethics. I’m not compromising my beliefs. In fact, I’m turning these kinds of expected conventions on their head.” Even when she did incorporate female nudity into her films, it doesn’t feel gratuitous, because it is oftentimes nudity in the course of every day. I think about that scene in Student Nurses where they’re all getting ready to go out and they’re just like, “Oh, I want to wear that shirt!” So, they just like switch shirts; a very normal thing that happens all the time. It’s really de-sexualizing.

MMS: You have this line in the book that I love so much: “Eventually, after the delicate courtship of six months of emailing, I was in Stephanie Rothman’s home, having the first of many conversations, formal and informal, I was to have with the director.” What has the experience and the process been like for you to be able to spend time with your historical subject, and she’s a very real person!

AK: I was so excited and so happy that she was able to give me the time, and she was so generous with her time. She was completely unvarnished in her conversation. It really helped get a better sense of her, both as a filmmaker, but also as a person, which then again helped me situate her historically in these varieties of different modes. It really helped get a better sense of her, both as a filmmaker, but also as a person which then again help me situate her historically in these varieties of different modes.

It was really thrilling, because I was finally being able to get answers to questions that had just been building and building and building, particularly for someone like Rothman, who is not completely absent from the historical record, but is present in small but contradictory ways.

It was a lot of, “So in 1978 I read that you were in making a movie in New York at the same time, you were making a movie in LA? Is that true?”

MMS: How does she answer that? Because I’ve had that exact same experience where you really go in as the film historian — and even a little bit as a grad student —

AK: 100%!

MMS: Here’s my timeline. Here’s my clippings, and you’re asking the real person, and they’re like, “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

AK: I told her I saw this weird thing in the Academy Library, “You got an award called the Stanley Cup?” And she said, “I don’t know what that is.” But for most things, she was ace at answering those timeline questions. One of the reasons it took me six months for her to say “Yes, I’ll talk to you,” is that she felt she had been so mistreated in the press. At that point I could have been literally anybody. She didn’t care that I was in academia versus writing for Variety. When she finally said yes, she was very clear: “Well, let me see this piece. What article did it come from? This is wrong. This is wrong.” She was really into correcting the historical record, and that was super helpful.

When she didn’t know, she just said, “I don’t know,” and for some of the other things she really wanted to dig in. I feel like every time she corrected a piece of information it was like, somehow, an imaginary letter to the editor the first time that piece came out.

I will say one of the things before she agreed to meet me was I had to send her a bibliography of everything I had already found! She said, “I don’t want to waste my time and tell you stuff that you could find somewhere else.” She is not one for wasting time. So, it was great. Speaking with her is always great. The deeper I got into the project, and the more I got into actually writing, the more it became, still thrilling, but a little nerve-wracking, because, as you said, she is a real person, and she wanted to read everything.

MMS: She read your manuscript?

AK: No, she didn’t read the manuscript. She is reading the book right now, and there are changes in there in how I think about the films that have evolved from how she and I initially discussed them. Some of them she’s not going to love, and that’s just what it is. But every article I published that had to do with her, every book chapter, she read after it was published. She ever came to a presentation I did about her at USC. She was in the crowd, and I was talking about her. It was surreal!

MMS: Did you know she was going to be there?!

AK: I told her I was going to be in California to see if she was free to meet up, and she said “Oh, I’m going to come.” And, well, I can’t say no! Thankfully, I was specifically talking about the paradigm of exceptional women and using her career just as an example, and she was totally into it, so any awkwardness was avoided.

At some point I had to figure out — because I like her very much as a person — how to bracket how I feel about her as a person versus a historical object, this case study, which is part of this bigger argument that I’m putting forward, which is both about her, but also not about her.

MMS: Because you’re developing your ideas, and it’s a process. From when you start working on this, early on in your graduate work, and your learning curve and your evolution as a historian, and thinking about this topic shifts and grows as it should. To be able to stay close and honor Stephanie Rothman’s legacy and her history, and be able to have room for yourself to grow is an interesting experience.

AK: It’s tricky in a way that’s incredibly rewarding. I heard her on a podcast kind of halfway through our journey together describe one of her films using the language I had used to describe the film. First, this is awesome! But then I panicked for a minute and thought, “do I now have to change how I’m describing this film so it doesn’t seem like I’m parroting what she said?!”

I constantly evolve in the ways that I talk about her work, because she is now in this incredible phase of rediscovery. Her films are being shown all the time. They’re being restored by MoMA and by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Science; she’s in an exhibit at the Academy’s new museum; and she’s been in New York and Canada a couple of times this year doing Q&A’s with her screenings. She’s on the Stephanie Rothman World Tour that she should have been on her entire career!

I constantly evolve in the ways that I talk about her work, because she is now in this incredible phase of rediscovery. Her films are being shown all the time.

MMS: Something that I have felt over and over again in interviewing the women filmmakers from this period is that we go in as historians. We’re so excited. We’re so thrilled. We’re so grateful that they’ve agreed to talk to us. I’ve learned this now more than in the beginning when I didn’t understand this — these are real filmmakers and that is a traumatic past. That’s a past of so much work and so much opportunity that she and so many women during this time didn’t get to see through. Stephanie made all of those incredible films. And then in 1974 made Working Girls and that’s it. That’s crazy! That’s awful.

How have you thought about the celebration of something that has so much disappointment in it?

AK: I think that I was concerned about my timing, particularly because her husband, Charles Swartz, who she spent her entire career working with, had passed not long before I started reaching out to her. I was concerned that his passing and, as you said, the trauma of what she had spent half of her life trying to do, would combine in a way that she would just want to fully move forward, and not think about it at all.

But in part, the opposite happened. I think, after Charles, it was a way for her to revisit their partnership — their professional partnership — and the way that had informed so much of what their lives had been. It wasn’t until 1984 — 10 years after her first film — that she finally said to him: “I quit. I’m not doing this anymore.” A couple of days later he said, “If you’re done, I’m done, too.” I think it was a way for her to celebrate the work that they had done together.

Working Girls is her “favorite” of her films. It is the one that is most autobiographical. But she doesn’t talk about it as much as others, I think in part because it’s also the one that she had the smallest budget for, the shortest amount of time to make it in, and it’s her last movie. She knows that had she been at her normal benchmark, it could have been much more of the film that she wanted.

MMS: I’m so glad she was up for it, of course. Because you don’t really know which way it’s going to go. It took me a while to learn that. And in some ways, it’s better, as the historian, as the interviewer, to not know, and just go in prepared and hope for the best.

AK: I think I was also somewhat well served by the fact that this was the first time I had interviewed a filmmaker like that. I had done ethnographic interviews before, but never a filmmaker, and like this —

MMS: Like an oral history.

AK: I was lucky in that I had read an oral history that I really liked–

MMS: We have to stop and give a moment to Jane Collings and her oral history of Stephanie Rothman.

AK: Her oral history is incredible. I have it printed out in a binder because I would read it like a novel!

MMS: Absolutely. Me, too!

AK: I had read an interview with the filmmaker Anna Biller done by Elena Gorfinkel. As a very eager grad student I emailed her: “Your work is amazing. This is who I am. This is what I’m about to do. I have a feeling you know who Stephanie Rothman is. Do you have any pointers?” And Elena, being one, an incredible scholar, two unbelievably gracious, and three, recognizing that another feminist historian needed some help, said “Let’s set up a time.” I called her and we just talked through it.

So I had Jane Collings’ work; the framework Elena provided; my mentor, Julie Turnock, who was always telling me to just go for it; and Stephanie, who was just ready to talk. It really was a perfect storm of circumstance and support.

MMS: Let’s bring this history into the present. You’re the director of the Indiana University Cinema. And you’ve written about current trends of art house exhibition. It feels like in the last 10 years, especially in the last five to seven years, streaming platforms and DVD and Bluray releases — Criterion, Shout! Factory, Kino —

AK: Vinegar Syndrome!

MMS: Yes! Are distributing work by women filmmakers; folks that have not been represented in these kinds of commercial releases; some have restorations and extras, interviews and commentary. How do you describe the current moment?

AK: I am of two minds when I think about this. One is, I’m ecstatic, because the only way I discovered that Stephanie Rothman existed is because I walked into a video store [Kim’s Video] and picked up one of her DVDs and said, “What the heck is this? And who is this person?” It was the beauty of walking into a video store and benefiting from the work of these distributors.

That process of discovery has been reshaped by distributor retail websites. What has happened on these websites [American Genre Film Archives, Criterion Collection, Vinegar Syndrome], is that there is now at least a loose packaging of “Women in…” that people can begin searching through with more direction than wandering around a store and hoping something catches your eye.

MMS: As much as I can’t stand the “woman filmmaker category,” this is a situation where it’s useful.

AK: It absolutely is! There is the historiographic mode of recovery and reappraisal — for most of these films and most of these women, it’s better described as discovery and appraisal. We’re not “reappraising” anything; they were not appraised in the first place! I get somewhat nervous about the idea that when we have access to these things, we essentially discover them out of context. Then we don’t get the full picture of why it’s the first time someone is hearing about Stephanie Rothman. To me, it plays into the paradigm of exceptional women again. For me to stand in a classroom of undergrads and talk about the disparity of women directors, and have students who raise their hands [to say], “Yeah, but there’s like 5,000 titles of films directed by women on Criterion Channel…,” you start to fall into the same trap again, right? And so, I am all for the discovery, the rediscovery, the appraisal, the reappraisal. But I do get concerned when it happens out of context. One of the things that I think has been beneficial is that art house theaters are taking up these films and not just throwing them up on screen, but curating them as series that have history and context and conversation around them, as only art house theaters can!

MMS: Okay, this is one last question, that’s really just for me. The International Women’s Film Festival in Toronto. You talk about in the book. Stephanie was there. Shirley Clarke was there. Is that the one that Agnès Varda was at also?

AK: I think so.

MMS: Have you ever found a flyer or an ad for it?

AK: The only thing I found was a notice in Rothman’s file at the [Margaret] Herrick Library. I have looked for it and that’s the only place I saw it.

MMS: Barbara Peeters, a contemporary of Stephanie’s and an exploitation director, told me about a Canadian feminist film festival that her films were at and she talks about meeting Shirley Clarke and drinking gin with her. And maybe Viva was there. Maybe Varda. Maybe Barbara Loden. I don’t think it’s the same one, but I don’t know!

AK: I don’t know and it’s the most generic title to research. Stephanie’s overriding memory of it was [that it was] the first time she met Shirley Clarke.

MMS: Yeah, and that’s what Barbara Peeters has said. “That’s when I met Shirley Clarke, and it was great.”

AK: What is this magical film festival?!

MMS: Did it really happen?! If there’s one archival thing I’m looking for, it’s the program to this film festival.

AK: If I come across it, even a mention of it, I will let you know!

MMS: I will do the same!

Click here for a free download of the table of contents and first chapter.