By Seung-hoon Jeong

When Bong Joon-ho’s Okja (2017) was booed with the Netflix logo appearing on the screen at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, nobody could have imagined that another Netflix-premiered film would win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival just a year later: Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma (2018). Of course, this drastic change was a matter of controversy for a while. Okja, boycotted by major Korean exhibitors, was rarely shown in the director’s home country theaters. The two largest US movie theater chains (AMC Theatres and Regal Cinemas) refused to screen Roma because their policies required an interval of at least 90 days between theatrical release and home viewing. Steven Spielberg disapproved of straight-to-streaming films’ eligibility for Academy Awards though he did not mention Roma, which nonetheless took three Oscars, including Best Picture, in 2019. The question ‘What is Cinema?’ then underwent a significant shift after the earlier ontological debate around the death of celluloid film and the birth of digital cinema. The thing was not simply how to accept and project ever-evolving digitized cinema in the theater, but whether the theater itself was a necessary condition of film culture or at least its privileged venue prioritized over internet platforms. Netflix was aggressively obtaining (even exclusive) distribution licenses and ambitiously investing in film production, too, creating ever more Netflix originals released only on Netflix. Threatened by this hybrid competitor, the existing cartel of film producers and distributors tried to defend their interests, often in the name of theater-based cinephilia, in vain.

Paradoxically, Roma was acclaimed for a cinematic charm that one could fully appreciate only on the big screen, bound in the dark Platonic Cave of fascinating shadows. Its vast black-and-white canvas, its multilayered mise-en-scene filled with details, and its Cuarón-esque long takes and tracking shots bring back Bazinian realism par excellence, letting things speak for themselves and inviting attentive spectators to interpret them freely. From the static first shot of the ground being cleaned with water over and over again, to the tilt-up last shot of the sky above the house, every moment in this ‘art film’ abounds with pure optical and sonic elements. Each of these components was directly captured from diegetic reality without attention-manipulating cuts and computer-generated effects. At times the film might test some viewers’ aesthetic patience with its slow pace, but it opens the sensational dimension of things and nourishes their symbolic implications, which often emerge retroactively. In the opening shot, an airplane is reflected on the surface of the water like a moving dot but is erased as Cleo, off-screen, washes the ground; a similar plane is seen flying across a clear sky in the ending shot when Cleo is going up to the rooftop with laundry. Her labor continues, grounded in a harsh reality without much chance to fly away, but her gaze changes from looking down to looking up as she gets integrated into the family she serves through various events occurring between the beginning and the end of the plot. In the theater, we are forced to follow and endure these events with her while all such details attract our senses, activate our sensibility, and take time to be meaningful, which could pass unnoticed or be skipped on a small display screen. In short, the Netflix film promotes a genuinely cinematic experience that could not be possible on the Netflix website.

Roma promotes a genuinely cinematic experience that could not be possible on the Netflix website

Netflix’s self-contradictory engagement with cinema takes a step further in a recent Netflix show that may deserve critical attention. Voir (2021) is billed as “a collection of visual essays for the love of cinema” and produced by David Fincher, whose past decade has been increasingly involved with Netflix dramas such as House of Cards (2013-18) and Mindhunter (2017-19). But as an established film auteur, Fincher sheds light on what cinema is in this series of six 20-minute episodes where film lovers and journalists celebrate film history, talking about the cinematic moments, characters, and crafts that thrilled, perplexed, challenged, and forever changed them. Notably, three of the episodes come from Taylor Ramos and Tony Zhou, the creators of the YouTube channel “Every Frame A Painting,” which has been known for quality analyses of film scenes, contributing to the new tradition of verbal criticism in cinephile culture. In other words, Netflix supports the collaboration of a filmmaker, critics, and YouTubers to reflect on the nature and power of cinema amid a changing media environment. Its service is thus not limited to film production and distribution, but includes leading film criticism and discourse on cinema in general across its different industrial and cultural sectors. No longer a mere streaming platform, Netflix invites and incorporates all visual media agents to set the agenda about cinema, looking back on its past and looking forward to its future.

For instance, the first episode, “Summer of the Shark,” encapsulates cinephilia via a film enthusiast’s nostalgic recollection of her adolescent initiation into the screen world through Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) in the mid-1970s. As she says, one falls in love with cinema when spectacles surge with emotions, when legendary scenes appear real and sincere, when repeated viewing always brings discoveries, when the eye does not see but “feels,” when a singular film, like Jaws, changes the way of viewing films and reshapes film history as well as a whole generation. This cinematic experience fills one with extraordinary feelings that transcend one’s daily spacetime, familiar world, and fixed individuality.

Let me draw more attention to the role of the theater here. The black box spatially conditions this transformative experience; separated from everyday reality, the theater fosters a temporary community of anonymous but like-minded spectators who may share their love of cinema in some cultural solidarity. Going to the cinema means joining this unknown public, becoming a citizen of the Cinema Republic by crossing the border between the bright mundane world and its dark, mysterious verso. The theater is a qualitatively different space in this sense, an ‘other’ place that differentiates the people inside it and the world outside it at once, and a heterotopia, to borrow from Michel Foucault. In truth, Foucault’s list of heterotopias––cultural or institutional “counter-sites” that disturb, transform, mirror, upset, represent, or invert all the other sites––includes the movie theater as juxtaposing several incompatible areas in a single place. Cinema displays a montage of otherwise unrelated locations, peoples, and events far beyond the range of our ordinary life, overwhelming our senses immeasurably. Its sublime images and sounds sublimate our minds. Salvatore sheds tears with a smile when even bits of old kiss scenes, censored but stored by his film mentor, flood the big screen in the finale of Cinema Paradiso (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1988). Doesn’t Jean-Luc Godard’s saying that we look down at television but look up in the cinema imply more than our posture?

It is no surprise that Voir compares two media in the fifth episode, “Film vs Television.” A film can be artistic when unfolding high-resolution images in a deep and wide mise-en-scene, giving importance to silence as much as sound, or preserving the authenticity of a continuous event without interruption. By contrast, TV delivers low-quality visuals of the ordinary world through analog signals, focusing on conversation or information in close-ups and cutting off any unnecessary duration. But the crucial point of this episode lies in the new millennial change brought by digital TV, HDTV, and big screen TVs that enable the use of the cinematic language in TV shows. HBO established this trend by making The Sopranos (David Chase, 1999-2007) look like a film aesthetically, blurring the traditional line between the two formats. Now Netflix and other operators of over-the-top broadcasting services such as Disney+ and Apple TV+ produce drama series that users can enjoy just like long films or film series.

As we all know, the COVID-19 pandemic has only boosted this platform economy. People have spent more and more time on streaming products while telecommuting is normalized, cinemas are closed, and home theater systems are affordable. Binge-watching has also facilitated cinematic spectatorship at home. Squid Game (2021), Netflix’s most-watched series, went unprecedently viral partly thanks to the simultaneous release of its nine episodes, all consumable in one go. Of course, the series’ surprising success was attributed to many factors, including its high production value. Written and directed by Korean filmmaker Hwang Dong-hyuk, Squid Game displays cinematic qualities in all aspects, from cinematography and editing to art design and sound, like a well-made film. Moreover, this survival drama diegetically shifts from a miserable life world to a fantastic yet fatal playground where childhood games turn into a bloody ‘war of all against all.’ The game island here appears as a violent heterotopia that could visually disturb average TV audiences but allegorically remodels, overturns, and supplements the free-for-all outside world in complex manners.

Not coincidentally, such a cinematic experience of a disastrous fantasy reflecting brutal reality is what many contemporary dramas offer, including post-Squid Game Korean series that hit the top of the global Netflix chart like Hellbound (Yeon Sang-ho, 2021) and All of Us Are Dead (Lee Jae-kyoo & Kim Nam-su, 2022). Viewers are ever more absorbed into the dystopian heterotopias staged in today’s cinematic OTT dramas, which differ entirely from comfortably watchable soap operas. What is cinematic here is not only the visual language or the mode of reception but the shows’ creative and critical engagement with reality. Their growing integration of the disaster genre or the ‘cinema of catastrophe’ is especially noticeable. This genre was established in ‘70s Hollywood with a focus on mainly natural or ahistorical disasters, but its significant post-9/11 trend is to ‘remediate’ or ‘premediate’ more realistic events like terroristic attacks. Even purely fictional catastrophes have been increasingly resonating with various global crises, present or potential. The zombie apocalypse mainstreamed since 28 Days Later (Danny Boyle, 2002) or a comet’s collision with Earth in Don’t Look Up (Adam McKay, 2021) provoke thought experiments on hypothetical situations, asking what would happen if current world risks, like any pandemic or climate change, indeed go beyond human control. By extension, if not a disaster film per se, Squid Game thrillingly captivates global audiences with hypothetical survival games while confronting them with disastrous world issues generated in today’s neoliberal global order: the debt-driven economy, limitless competition, winner-take-all scenarios, class polarization, and the law of the jungle. Instead of serving as escapist entertainments soothing our fatigue from the Covid pandemic, such streaming dramas bring the cinematic experience of reawakening to the global system and its catastrophic antinomies, including, broadly, the very pandemic.

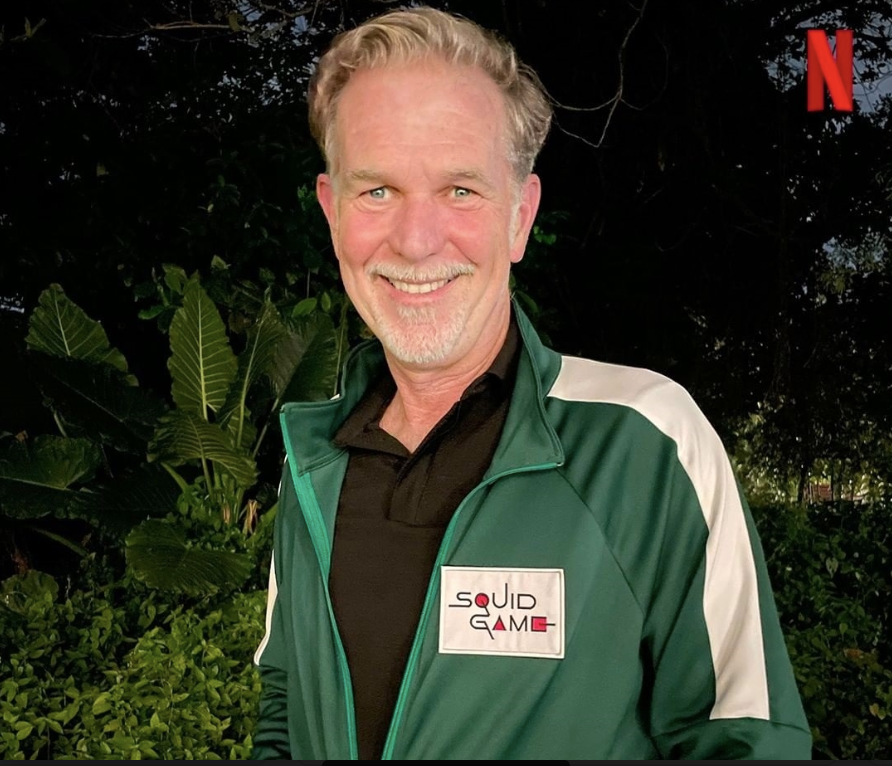

The problem is that this cinematic experience is enabled and structured by the cultural industry rooted in the capitalist system of globalization. One may remember the bizarre scene of the Netflix CEO wearing the abject Squid Game protagonist’s tracksuit and smiling like a jubilant child at his $283 billion company’s quarterly earnings interview. The streaming media giant’s stock price rocketed exponentially thanks to the relatively cheaply-produced local drama’s globally appealing harsh critique of capitalism. Shortly after the release of Bong Joon-ho’s smash hit Parasite (2019), Squid Game became another global Korean product that manifested the ‘performative self-contradiction’ of the capitalist market capitalizing on anti-capitalist culture and vice versa. This paradoxical feedback loop of mutual benefits underlies today’s cultural survivalism. Media content can depict capitalistic catastrophes more cinematically by depending more financially on the capitalist system. Conversely, this system can reinforce itself more powerfully by embracing and investing in such critical content more benevolently.

Let me conclude by going back to Voir. It showcases the expansion of this contradictory entanglement toward the area of critical reflection on cinema itself. It looks like a manifesto from Netflix declaring that although the age of cinema has ended, the cinematic experience will continue to be updated and upgraded globally through digital TV and OTT platforms, even taking advantage of such global crises as the pandemic. If this is a cultural ‘new normal,’ we could expect to see even more films and dramas reflecting how our lives are threatened by the global system on the one hand and to notice such cinematic content reproduced by post-cinema media corporations embodying the same system on the other. But we cannot anticipate how long this productive contradiction will perform itself and if or when it might reach a tipping point of self-implosion or self-transformation. At least one thing is sure: Netflix has become a synecdoche for the ever-proliferating global digital network of all cinematic content, leaving ever less room for its outside. The new normal is thus abnormal; the more ‘Netflix-ized’ the content is, the more cinematic it can be.