By Mani Sharpe & Alan O’Leary

In this dialogue, Mani Sharpe and Alan O’Leary discuss cinema and colonialism in relation to Sharpe’s Late-colonial French Cinema: Filming the Algerian War of Independence, forthcoming (February 2023) from Edinburgh University Press, and O’Leary’s The Battle of Algiers (Mimesis International 2019).

Why these two books?

Mani Sharpe (MS): I wrote the proposal for my book in 2015, after finishing an unpublished PhD at the University of Newcastle. Although my PhD and this book share a comparable interest in cinematic representations of the Algerian War, there are also two notable differences between the two projects: firstly, where my PhD was a comparative study of French and Algerian filmmaking, the book is focused solely on the work of Francophone directors (excluding the Canadian Mark Robson), and, secondly, where my PhD was largely concerned with the post-colonial epoch, the book is more concerned with the liminal period between colonialism and post-colonialism. In my original proposal to EUP, I had based the book around ‘screens’ and ‘screening’ (it was initially called Screening the Algerian War), although neither of these concepts eventually proved to be as theoretically useful as I initially thought.

I suppose that the main reason that I wrote this book is because I wanted to go beyond the canon of (mostly New Wave) French films that are generally associated with the decolonization of French Algeria, including Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7/Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), Alain Resnais’s Muriel ou le temps d’un retour/Muriel or the Time of a Return (1963), and Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Petit soldat/The Little Soldier (1960/1963). Although I do touch upon these canonical works at various points in my monograph, I also seek to go beyond them, opening up, in turn, an unappreciated seam of late-colonial films by cineastes such as Jacques Dupont, Yann le Masson, Guy Gilles, Marc Sator, Paul Carpita, and Jean Herman, amongst others. In terms of methodology, I was influenced by the ways in which scholars such as Guy Austin, Naomi Greene, and Kristin Ross1 have managed to blend cultural history, critical theory, cultural studies, and rhetorical writing techniques in their own works, edging away from traditional historiography to a more conceptual understanding of historical events. I think that this is something that we both try to do, although in different ways.

Alan O’Leary (AOL): I had taught, and I would say lived with, The Battle of Algiers since I was a graduate student, and my monograph on the film is an act of ‘retrospectatorship’, Patricia White’s term for a mode of re-viewing shaped by the experiences and memories it elicits in the viewer. In particular, I wanted to better understand the film’s power, the exhilarating effect it had on me when I first saw it. I think the film is important enough (not just to me) to warrant a book-length study, and my model was the more scholarly entries in the BFI Film Classics series, particularly David Forgacs’ book on Rome Open City and Robert Gordon’s on Bicycle Thieves, two books which pack an enormous amount of thinking and research between slim covers.2 My own thinking, research and reading (there is a lot of criticism and scholarship on The Battle of Algiers) led me to ask three questions that I try to answer in my book’s central chapters: What is the role of the city of Algiers in the film? What are the consequences of its address to multiple audiences, including those in colonizing Europe? What are the effects of the film’s activity of reenactment (especially the famous restaging of protests) and what can these tell us about revolutionary agency? More than that, though, I wanted my account of the power of The Battle of Algiers to shed light on the means and capacities of historical and political cinema as such.

‘Late Colonial’ and ‘End-of-empire’ cinema

MS: For many years, I struggled to lexically define my corpus, which is composed of fifteen central case studies of late-colonial French cinema. I remember standing in the library at The University of Leeds with two edited collections – one entitled Culture coloniale 1871-1931/Colonial Culture 1871-1931,3 the other entitled Culture Post-coloniale 1961-2006/Postcolonial Culture 1961-20064 – and thinking to myself: well, neither ‘colonial’ nor ‘postcolonial’ seem appropriate to the films that I am studying, so what should I call them? Anecdotally, I initially attempted to circumnavigate this problem by calling my corpus ‘de-colonial French cinema’, in the same way that Hannah Feldman names her corpus ‘de-colonial art’,5 before ultimately abandoning the idea. This decision, taken after advice from Jim House and Rebecca Jarman, both of whom work at The University of Leeds, was one through which I hoped to avoid any confusion between my case studies and the recent de-colonial turn in the Humanities, with the former remaining obliquely tethered to a colonial ideology that the latter unequivocally repudiates.

The main reason that I considered ‘late-colonial’ to be an appropriate term is because it doesn’t designate a specific political position, whether right wing, left wing, anti-colonial or pro-colonial, but is more temporally inflected, indicating the decline of the colonial system. Given that many of the films I study endorse radically different political perspectives, yet were all made towards the end of colonialism, ‘late-colonial’ seemed best placed to capture that nuance. There are clear parallels in our thinking here.

AOL: I settled on ‘end-of-empire cinema’ to characterize The Battle of Algiers for various reasons. I suppose I wanted to avoid, first of all, falling into an exasperating debate about whether the film was ‘appropriately’ political, or ‘really’ Third Cinema, and all that. (This is a debate that dates to the release of the film, and culminates in the prescriptive discussion in Mike Wayne’s 2001 Political Film: The Dialectics of Third Cinema, my book’s critical antagonist).6 I wanted a term to point to the ambivalence of the film: its location between genres, between protagonists, between nations and between periods. The Battle of Algiers has often been discussed as ‘birth of a nation cinema’, usually with reference to the Italian neorealism of Roberto Rossellini (Rome Open City of 1945 and especially Paisan from the following year). But my work revealed a prior origin for the film in the cinema of the fascist period, and I wanted a term to signal this. I read Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s important book on fascism and colonial filmmaking, Italian Fascism’s Empire Cinema (2015),7 and realized I could adapt the term ‘empire cinema’ to indicate the liminal place (and status?) of The Battle of Algiers. You’ll remember that the film ends in a peculiar suspended future in the past, with the announcement in voiceover of Algerian independence to come two years after the events that close the film. So, we really are left, as the film closes, at the end of empire, awaiting rather than attending the birth of the nation. The film is as much about the exhaustion of the colonial project as it is about the success of revolutionary nationalism.

An inflected Orientalism

MS: Many of the films in my book draw from the type of colonial culture analyzed by scholars such as Elizabeth Ezra.8 To take a few examples, in both Jacques Dupont’s Les Distractions (1960) and Alain Cavalier’s L’Insoumis (1964) we find the type of elite military protagonists that were originally woven into classic colonial films such as La Bandera (Duvivier, 1935) and L’Atlantide (Pabst, 1932). The difference here is that colonial films often placed these protagonists into contact with the so-called colonized Other (Pabst’s film, for example, features a famous scene in which a legionnaire is absorbed into an exotic harem, somewhere in the Sahara), whereas late-colonial films tend to erase the colonized population from the frame of representation altogether. The sense of absence generated through this erasure is something I talk a lot about in Chapter 6 of my book, focusing, in particular, on two films made by the settler community in French Algeria. Both Au biseau des baisers (Sator and Gilles, 1962) and Les Oliviers de la justice (Pélégri and Blue, 1962), for instance, chronicle a curious tension: between a desire to obsessively look at the colonized landscape of French Algeria, and a desire to obsessively look away from the colonized communities of French Algeria. Neither film explicitly promotes the idea of colonialism, yet both are subtended by a panoptic imaginary that is fundamentally colonial.

AOL: My book is written against a moralistic or prescriptive idea of political cinema that wants to find in it ‘the unblemished blueprint for our tomorrow’ (to quote myself in rhetorical mode!). I consider it absurd to dismiss a film ‘politically’ because it does not conform to a particular theoretical idea of what political cinema ideally ought to be. My guiding principle in the book is one expressed by Judith Butler, who denies the possibility of any ‘pure’ opposition or ‘transcendence of contemporary relations of power’. Politics for Butler, and political cinema for me, is a practice that emerges as a ‘difficult labor of forging a future from resources inevitably impure’.9 What that means is that I try to trace in The Battle of Algiers a survival or inflection of colonialist tropes, even as the film hymns anti-colonial aspiration and agency. In fact, I argue that The Battle of Algiers is an Orientalist text (this is the theme of chapter 3), and moreover, that the film derives its undoubted power precisely from this. Obviously, this argument has a degree of perversity about it (Battle is usually seen as the quintessential anti-Orientalist film), but I hope it grasps how the means of The Battle of Algiers, and of political filmmaking as such, are inherently ambivalent: always already compromised, so to speak. The point is that it is from this ambivalence that political cinema derives its ability to speak, to be understood and even to inspire.

Space and gender

MS: It seems to me that our books both attempt to theorize space in a way that goes beyond the historical to the conceptual. In Chapter 1, for example, I write quite a bit about how both Adieu Philippine (Rozier, 1963) and La Belle vie (Enrico, 1964), represent the commodified home as a haven, or protective shield, against the potentially threatening aspects of the War (spiraling violence, ethnic difference, colonial guilt). Underpinning many of the arguments that I propose within this chapter is the spatial concept of privatization, a concept notably elaborated by Henri Lefebvre in his 1961 monograph Critique de la vie quotidienne II, Fondements d’une sociologie de la quotidienneté/Critique of Everyday Life: Foundations for a Sociology of the Everyday.10 A phenomenon at once social and cultural, architectural and urban, individual and collective, according to Lefebvre, privatization emerges in moments of national strife, for example urban renewal, political crisis, or war, when the domestic realm acquires an inflated, almost metaphysical, importance. Both Rozier and Enrico’s films are as concerned with the looming threat of the War as they are with the sublime beauty of domestic space.

In Chapter 6 of my book, I approach the question of space from a different angle, focusing more upon images of public space and the urban geography of colonial Algeria. Key to these discussions is the concept of landscape, with this concept having notably been theorized by thinkers such as Jacques Leenhardt, Ella Shohat and John Zarobell.11 I am particularly interested in how settler films like Au biseau des baisers and Les Oliviers de la justice depict the landscape of Algeria from a panoramic perspective, harking back to the visual impulses that governed Renaissance painting and colonial cinema. These are questions about film form as much as they are about film content.

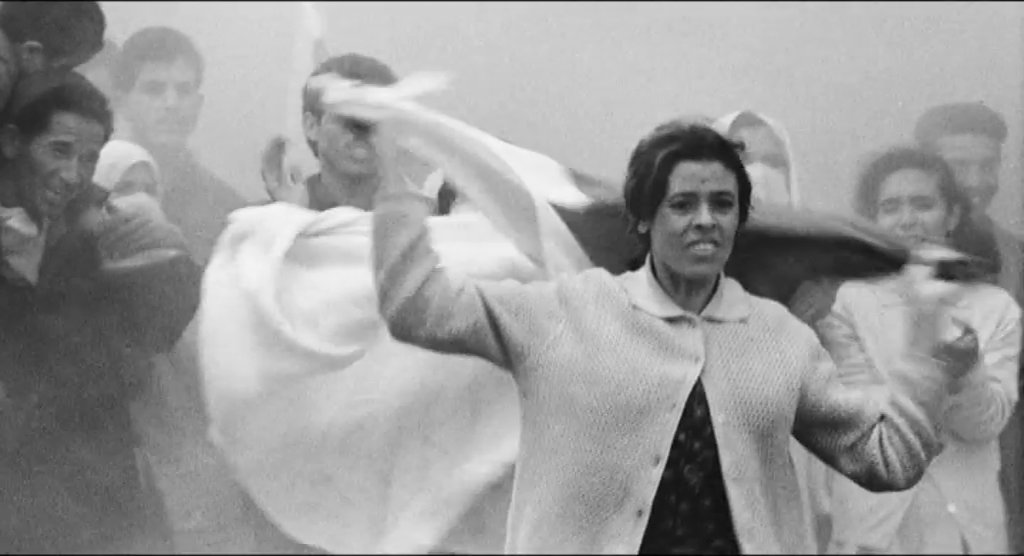

AOL: My concern with space in The Battle of Algiers began with a sense that there was an over-emphasis in the scholarship on the presence of the Casbah in the film (I discuss this in chapter 2 of my book). Early in the film, an opposition is set up between European city and ‘indigenous’ Casbah using onscreen text and a pan and zoom over downtown Algiers. Critics have taken this very Orientalist opposition to be maintained by the film, to the extent that even those obviously familiar with the film have mistaken the character of the architecture that appears in the film’s invigorating coda (when the Casbah is shown only from the outside at night). Paying a trip to Algiers in 2015, and reading architectural and other histories (the archival work on protests in Algiers by your Leeds colleague Jim House was invaluable),12 I came to realize that many of the locations shown were instead from 1950s housing projects that can be described as neither European city nor Casbah. The presence of these ‘hybrid’ spaces was not of incidental interest. Rather, the film’s keen attention to the historical character of particular (and not merely picturesque or ‘representative’) locations speaks of the interstitial or liminal moment between empire and liberation which the film at once shows and formally enacts in the coda sequence. Notions of Third Space from Edward Soja and Homi Bhabha suggested themselves in order to describe and theorize how the coda sequence,13 located spatially and temporally beyond the main story and featuring none of the main story’s characters, evinces something politically new, unpredictable, hybrid. Bhabha says that social and representational novelty emerges unpredictably in or from the interstices of the dominant political and discursive order. The coda to the The Battle of Algiers confirms this: the six-minute coda, which is my book’s key exhibit, shows and is what Bhabha calls a Third Space.

But beyond the theme of space, I’d say that both of our books identify and investigate a link between late colonialism or end of empire and gender. For example, some of my third chapter talks about the paratrooper as embodiment of colonial power, a theme that you also deal with.

MS: Most of the protagonists that we find in late-colonial French cinema are male soldiers: whether prospective or returning conscripts, reservists, legionnaires, or paratroopers. Alongside yourself, Philip Dine has talked eloquently about the mythological status of the paratroopers, analyzing how they came to occupy an almost transcendental position in literary narratives of the period: as supremely virile paragons of colonialism.14 In my own book, I speak at length about how this myth was likewise transmitted through films such as Lost Command (Robson, 1966), although my own analysis draws instead from critical concepts aligned with star studies, and in particular thinkers such as Richard Dyer, Ginette Vincendeau, and Sarah Leahy.15

In addition to the myth of the paratroopers, another influence on the androcentric imaginary of my corpus can be located in the ethos of the Hussars (sometimes spelt ‘Hussards’ in line with the original French). Originally employed within a militarized framework to designate a type of cavalryman, the term ‘Hussar’ notably acquired a new significance during the early 1950s: firstly when aspiring author, Roger Nimier, foregrounded it in the title of his 1950 novel Le Hussard bleu,16 a work, unsurprisingly, about ten hussars who form part of the French First Army during its advance towards Germany in 1944-45; and then in 1952, when journalist Bernard Frank used it in a scathing article, published in the politically committed, leftist leaning journal Les Temps modernes, to identify what he saw as an emerging right-wing trend in French literature. I talk a lot about how late-colonial French cinema mirrored this Hussar counter-culture in Chapters 3 and 4, specifically in relation to configurations of masculine identity (virility, emasculation, castration etc.). Jacques Dupont’s aforementioned Les Distractions is probably the best example of this. It is basically a very bad remake of Godard’s A bout de souffle/Breathless (1960), in which Jean-Paul Belmondo plays an ex-paratrooper turned journalist-dandy, who does little more than drive around Paris in his glimmering Austin-Healey, seducing women as cocktail parties.

AOL: I discuss gender in The Battle of Algiers in relation to Orientalism and the theme of address. I try to show that the ‘receivability’ of Battle (its legibility and popularity for multiple audiences—and I should say that I am careful to treat the film as popular cinema) implies and relies on the film’s Orientalism. Orientalism is the language Battle speaks in order to be understood, even as it deals with anti-colonial aspiration. And so, I read the film’s pairing and opposing of the two protagonists, hyper-rational French paratrooper colonel Mathieu (who confirms even as he complicates the paratrooper mythology) and illiterate Algerian revolutionary Ali La Pointe, as characteristically Orientalist. Ali is associated with the labyrinthine Casbah and emerges from it as colonial stereotype: based on a real revolutionary hero, he is an inspirational leader, but the film shows him as obstinate and passionate, slow to see reason. Mathieu, on the other hand, is a flattering portrait of what I call ‘the white male North’: however ruthless, he’s an ‘Enlightenment man’ who confirms the self-image of the colonizer as, in Edward Said’s words, the ‘White-Man-as-expert’.17 Of course, the film deplores his rationalizations (a horrifying montage of torture scenes directly follows his verbal defence of torture as method), but he remains rational. My point is neither to praise nor damn Battle for the use of an Orientalist opposition between ‘passionate Arab’ and ‘rational European’, but to argue that the film is constrained to speak at once against and from within ideologies of white racial supremacy generated along with European colonialism. We both also discuss the portrayal of women in our books: Algerian in mine, French in yours…

MS: To say that my book examines representations of French women requires a certain degree of qualification, namely as, in and of itself, this term doesn’t distinguish between French women living in colonial Algeria (known as French settlers); Algerian women living in Algeria (given that the French State considered them constitutionally French); and French women living in metropolitan France. In the interest of clarity, let me state that it is the latter that forms the central focus of at least one chapter of my book (Chapter 5), entitled ‘Female Citizens and Guilt Displacement’. Inspired by thinkers such as Susan Weiner and Susan Hayward,18 this chapter essentially aims to explore how late-colonial French cinema worked through the guilt of the War, firstly by shifting it from the collective realm of war and politics to the realm of individualised sexuality and emotions; and secondly by grafting this revised, sexual guilt onto the bodies of female protagonists, often depicted as consumed by irrepressible libidinous urges, or disloyal to their betrayed soldier-husbands. This chapter also includes analysis of what I personally consider to be two of the least analyzed yet most important late-colonial French films: Daniel Goldenberg’s Le Retour (1959) and Philippe Durand’s absolutely majestic Secteur postal 89098 (1961). Durand’s film drove me crazy for a good couple of months in 2021 whilst I struggled to work out what on earth it was about, and how to approach it. The director’s incredibly unconventional use of an epistolary sound track consisting of fragments of un-visualized spoken letters is particularly fascinating, especially in relation to how this sound track relates to the image track of the film, much of which is composed of scenes depicting women’s faces. I ultimately suggest that Secteur postal 89098 frames the female body as a screen upon which the traumatic testimony of the War is projected, through the disembodied speech of a soldier.

AOL: A shared theme in our books is how female characters tend to be valued, in the films we study, not in themselves, but inasmuch as they represent something. In the corpus you analyse, women are made to embody guilt, whereas for me (as discussed in my third chapter), in The Battle of Algiers, they bear the burden of national emergence, which is to say they are distilled to allegory as the film closes. As you point out in your review of my book, this is hardly a novel interpretation.19 But what I hope to have grasped in my analysis is how something in the Orientalist tradition of the exotic woman imagined in the harem, or — in French colonial cinema, say — in the brothel, equips that same fantasy woman to play a revolutionary role. She can represent threat, in other words, as well as desire. This helps to make sense of the famous scene in which Algerian women disguise themselves as European in order to cross military check points and plant bombs in the European city, a scene that alludes to Orientalist painting and films like Pépé le Moko (1937). My point is that it is not so much that the odalisque turns terrorist in Battle, but rather that she was terrorist all along. I should say that this interpretation of the film was found offensive by an Algerian academic colleague. (I think he felt it was disrespectful to the monumental status of the film in Algeria, and to the female revolutionaries on whom the characters in Battle are based.) But it illustrates Homi Bhabha’s well known argument that the colonial stereotype retains its ‘reality effect’ even after the demise of the colonial era, and even in texts explicitly opposed to colonialism. In the latter part of Chapter 3, I translate Bhabha’s argument about character onto the level of form. Just as the stereotype retains its reality effect, so a particular mode, Italian fascist empire realism, through which the colonized space came to be known and dominated in the first place, retains its epistemic charge in the era of decolonization. This is why I talk of the realism of The Battle of Algiers as finding an origin in empire cinema rather than, as is conventionally asserted, in the democratic cinema of post-WWII Italian neorealism.

The time time takes

MS: By far the most difficult chapter to write was Chapter 4 – about temporality and memory. There were several reasons for this. Firstly, this was one of the first chapters I wrote, in 2015, when the argumentative thrust of the book was still far from clear. Secondly, this chapter was actually initially more about allegory than it was about memory, and – as I would quickly come to realize – the whole notion of allegory, as a figurative device whose meanings can change according to context, is horribly complicated.20 I actually published what I now consider to be a very limited article on representations of memory in two late-colonial films, La Dénonciation (Doniol-Valcroze, 1962) and Tu ne tueras point (Autant-Lara, 1963), before almost completely rewriting this article in an attempt to improve it. The third reason that this chapter was so hard to write was due to the popularization of memory studies in the Humanities/French Studies, during the late 2010s, catalyzed, in particular, by the pioneering work of Michael Rothberg21 and Max Silverman.22 Trying to navigate through the vast volume of academic articles on the subject – choosing which to draw from, and which to discard – was a very complicated task. All in all, I think this chapter took me about four years to write. It was a real challenge.

AOL: Your difficulties resonate with me! My own Chapter 4, also on temporalities, was easily the hardest to write, and it still seems ‘raw’ to me when I look at it now. But it also seems to me the most interesting in the book — the chapter with the most potential to inform discussions of cinema and history beyond discussions of this particular film. I admit I just avoid the whole intimidating edifice of memory studies, beyond lamenting memory studies’ privileging of the trauma paradigm, which I consider inadequate to an account of the power of The Battle of Algiers. Instead, I focus on what you might call ‘performative history’ in relation to reenactment. (I mean the term ‘performative’ here in opposition to ‘representational’, again with Bhabha and Butler in mind.) Battle is renowned for impressive crowd scenes that reenact protests, along with the police and military response to these, on their original locations. And reenactment has become a key concept in discussions of film and history in important scholars like Robert Burgoyne. Burgoyne builds on philosopher of history R.G. Collingwood, for whom the mental activity of reenactment was the historian’s core method.23 According to Collingwood, the historian reconstructs events and infers causes through a kind of reenactment in the head. I have tried, instead, to present physical reenactment as a kind of communal thinking where bodies undertake in concrete space the work of historical imagining. The famous crowd scenes in Battle are a kind of meeting of anonymities in which the unnamed extra reenacts the individual historical experience ordinarily lost to narration. If the filmmaker (Gillo Pontecorvo, say, the director of Battle) can be a historian (this is the position of scholars like Burgoyne and Robert Rosenstone), then the same is true for the unnamed participants and extras in The Battle of Algiers, and so too the crowds they comprise.

Traveling concepts

MS: I suppose that there are concepts in this book that I think could be useful to other scholars. One of these is the notion of late colonial cinema, as a type of cinema that arose in a liminal period, between the colonial and the post-colonial. The other is redemptive pacifism, a term I use throughout my book to identify the curious dialectic that seems to exist in many of my case studies: between imagining the War in ontologically negative terms, as a source of pain and atrocity (the ‘pacifist’ element), and imagining France in ethically positive terms, as a country composed of absolved victims and antiheroes (the ‘redemptive’ element). This forms part of a broader interrogation of the ethical — rather than political — side of French narratives produced in the late-colonial period. From the sound of it, I think that we are both quite skeptical of the notion of political cinema!

AOL: The most productive concepts in my book are adapted from other scholars, but I hope I’ve put them to original use. I’ve mentioned a couple already, but I’ll add one from my conclusion, borrowed from Mary Louise Pratt: ‘autoethnography’.24 Pratt uses this term to describe texts in which the colonized present themselves in ways that engage with the colonizers’ representations. We can think of the Orientalism in Battle as autoethnographic in this sense: the film partly collaborates with and appropriates what Pratt calls the ‘idioms of the conqueror’, so as to ensure receivability even by hostile audiences. Thinking of film in this way is (yes!) to refuse a certain ‘aspirational’ (or paternalistic) strain of political film criticism — the sort that starts from what Bhabha calls a ‘prior political normativity’, meaning a set of prescriptions about the kind of content that should be contained in an appropriately political film and the kind of form in which to express it. Thinking of political cinema in terms of autoethnography assumes that the political is not illustrated but is instantiated as an inflection of existing modes and as a negotiation of existing relations of power.

Footnotes

1 Guy Austin, Algerian National Cinema (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012); Naomi Greene, Landscapes of Loss: The National Past in Postwar French Cinema (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999); Kristin Ross, Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1995).

2 David Forgacs, Rome Open City (London: British Film Institute, 2000); Robert Gordon, Bicycle Thieves (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

3 Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire, Nicolas Bancel, Dominic Thomas (eds.), Colonial Culture in

France Since the Revolution (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014).

4 Pascale Blanchard and Nicolas Bancel (eds.), Postcolonial Culture 1961-2006 (Paris: Editions Autrement, 2011).

5 From a Nation Torn: Decolonizing Art and Representation in France, 1945-1962 (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2014), p. 1.

6 Mike Wayne, Political Film: The Dialectics of Third Cinema (London: Pluto Press, 2001).

7 Ruth Ben Ghiat, Italian Fascism’s Empire Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015).

8 The Colonial Unconscious: Race and Culture in Interwar France (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 2000).

9 Butler quoted in James Loxley, Performativity (London: Routledge, 2007), p. 127.

10 Critique de la vie quotidienne II: Fondements d’une sociologie de la quotidienneté (Paris: L’Arche, [1961] 2008).

11 Jacques Leenhardt, Lecture politique du roman: la Jalousie d’Alain Robbe-Grillet (Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1973); Ella Shohat, ‘Imaging Terra Incognita: The Disciplinary Gaze of Empire’, Public Culture, 3: 2 (1991), pp. 41–70; John Zarobell, Empire of Landscape: Space and Ideology in French Colonial Algeria (College Station, PA: Penn State University Press, 2009).

12 See for example Jim House, ‘Colonial Containment? Repression of Pro-independence Street Demonstrations in Algiers, Casablanca and Paris, 1945-1962’, War In History 25:2 (2018), 172–201.

13 Edward Soja (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (Oxford: Blackwell); Jonathan Rutherford, ‘The Third Space: Interview with Homi Bhabha’, in Rutherford (ed.), Identity: Community, Culture, Difference (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990), 207-221.

14 Philip Dine, Images of the Algerian War: French Fiction and Film, 1954–1992 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

15 Richard Dyer, Stars (London: BFI, [1979] 2008); Ginette Vincendeau, Stars and Stardom in French Cinema (London and New York: Continuum, 2000); Sarah Leahy, ‘The matter of myth: Brigitte Bardot, stardom and sex’, Studies in French Cinema, 3: 2 (2003), pp. 71–81.

16 Le Hussard bleu (Paris: Gallimard, 1950).

17 Edward Said, Orientalism (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 235.

18 Susan Weiner, Enfants terribles: youth and femininity in the mass media in France, 1945-1968 (Baltimore, London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001); Susan Hayward, ‘Framing National Cinema’ in M. Hjort and S. Mackenzie (eds.), Cinema & Nation (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), pp. 81–93.

19 Mani King Sharpe, Review of The Battle of Algiers by Alan O’Leary, Transnational Screens, 13:1 (2021), 80-81.

20 Debarati Sanyal, Memory and complicity: migrations of Holocaust remembrance (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015).

21 Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (California: Stanford University Press, 2009).

22 Palimpsestic Memory: The Holocaust and Colonialism in French and Francophone Fiction and Film (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2013).

23 Robert Burgoyne, ‘Introduction: Re-enactment and Imagination in the Historical Film’, Leidschrift 24:3 (2009), 7-18.

24 Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, 2nd edn (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008).